По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

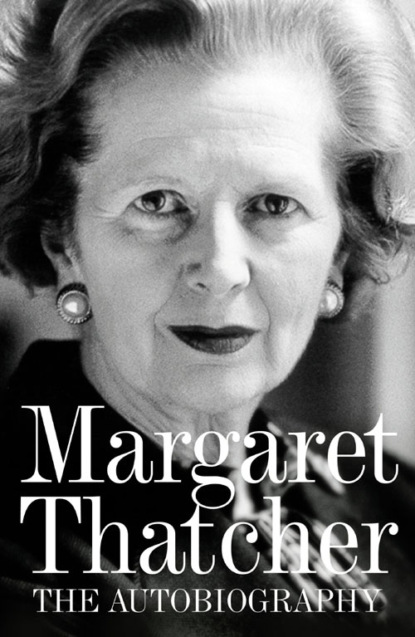

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There was further discussion in Cabinet in the autumn of 1971, and the Government allowed itself to be sucked into talks with the trade unions, who it was believed might be able to influence the militant shop stewards behind the occupation. The Economic Committee of the Cabinet had agreed that money should be provided to keep open the yards while the liquidator sought a solution, but only on condition that the unions gave credible undertakings of serious negotiations on new working practices. There was strong criticism of this from some of my colleagues, rightly alert to the danger of seeming to give in on the basis of worthless undertakings. But the money was provided and negotiations went ahead.

It was the unemployment prospect rather than the prospects for shipbuilding which by now were undisguisedly foremost. In November Ted Heath affirmed in a Party Political Broadcast that the ‘Government is committed completely and absolutely to expanding the economy and bringing unemployment down’. The fateful one-million mark was passed on 20 January 1972. On 24 February at Cabinet we heard that the Economic Committee had agreed to provide £35 million to keep three of the four yards open. John Davies openly admitted that the new group had little chance of making its way commercially and that if the general level of unemployment had been lower and the economy reviving faster, he would not have recommended this course. There was tangible unease, but Cabinet endorsed it and at the end of February John announced the decision. It was a small but memorably inglorious episode. I discussed it privately with Jock Bruce-Gardyne, who was scathing about the decision. He regarded it as a critical, unforgivable U-turn. I was deeply troubled.

But by now we all had other things to worry about. In framing the Industrial Relations Act we had given too much emphasis to achieving the best possible legal framework and not enough to how the attacks on our proposals were to be repelled. The same mentality prevailed as regards the threat which the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) posed to the Government and the country. We knew, of course, that the miners and the power workers held an almost unbeatable card in pay negotiations, because they could turn off the electricity supply to industry and people. Industrial action by the power workers in December 1970 had been settled after the setting up of a Court of Inquiry under Lord Wilberforce which recommended a large increase in February the following year. Within the NUM, however, there was a large militant faction at least as interested in bringing down the Conservative Government as in flexing industrial muscle to increase miners’ earnings. The NUM held a strike ballot in October 1970 and narrowly turned down an offer from the National Coal Board (NCB). Fearing unofficial action, Cabinet authorized the NCB to offer a productivity bonus to be paid in mid-1971. The NUM again turned the offer down, following which Derek Ezra, the NCB Chairman, without consulting ministers, offered to pay the bonus at once and without strings attached to productivity. Cabinet accepted this fait accompli. Perhaps John Davies and other ministers continued to monitor events. If they did I heard nothing about it.

Only in early December 1971 did the issue of miners’ pay surface at Cabinet, and then in what seemed a fairly casual way. The NUM’s annual conference that year had significantly revised the rules which provided for an official strike, so that now only a 55 per cent, as opposed to a two-thirds, majority was required. The NUM ballot, which was still going on, had, it was thought, resulted in a 59 per cent majority vote for strike action. Yet nobody seemed too worried. We were all reassured that coal stocks were high.

Such complacency proved unwarranted. At the last Cabinet before Christmas Robert Carr confirmed to us that the NUM was indeed calling a national strike to begin on 9 January 1972. There was more trouble over pay in the gas and electricity industries. And we only needed to glance outside to know that winter was closing in, with all that meant for power consumption. But there was no real discussion and we all left for the Christmas break.

There was still some suggestion over Christmas that the strike might not be solid, but two days after it began it was all too clear that the action was total. There was then discussion in Cabinet about whether we should use the ‘cooling off’ provisions of the Industrial Relations Act. But it was said to be difficult to satisfy the legal tests involved – ‘cooling off’ orders would only be granted by the courts if there was a serious prospect that they would facilitate a settlement, which in this case was doubtful. The possibility of using the ballot provisions of the Act remained. But there was no particular reason to think that a ballot forced on the NUM would lead to anything other than a continuation of the strike. It was an acutely uncomfortable demonstration of the fragility of the principal weapons with which the Act had equipped us. Moreover, important parts of the Act had yet to come into force, and we were also aware that there was a good deal of public sympathy with the miners.

The pressure on the Government to intervene directly now increased. Looking back, and comparing 1972 with the threatened miners’ strike of 1981 and the year-long strike of 1984–85, it is extraordinary how little attention we gave to ‘endurance’ – the period of time we could keep the power stations and the economy running with limited or no coal supplies – and how easily Cabinet was fobbed off by assurances that coal stocks were high, without considering whether those stocks were in the right locations to be usable, i.e. actually at the power stations. The possibility of effective mass picketing, which would prevent coal getting to power stations, was simply not on the agenda. Instead, our response was to discuss the prospects for conciliation by Robert Carr and the use of ‘emergency powers’ which would allow us to conserve power station stocks a few weeks longer by imposing power cuts. There was a great deal of useless talk about ‘keeping public opinion on our side’. But what could public opinion do to end the strike? This was one more thing I learned from the Heath years – and anyway, on the whole public opinion wasn’t on our side. A further lesson from this period – when no fewer than five States of Emergency were called – was that for all the sense of urgency and decision that the phrase ‘emergency powers’ conveys they could not be relied upon to change the basic realities of an industrial dispute.

The crunch came on the morning of Thursday 10 February when we were all in Cabinet. A State of Emergency had been declared the previous day. It was John Davies who dropped the bombshell. He told us that picketing had now immobilized a large part of the remaining coal stocks, and that the supplies still available might not even suffice beyond the end of the following week. Electricity output would fall to as little as 25 per cent of normal supply, drastic power cuts were inevitable, and large parts of industry would be laid off. The Attorney-General reported that the provisions of the Industrial Relations Act against secondary boycotts, blacking of supplies and the inducement of other workers to take action resulting in the frustration of a commercial contract, would not come into force until 28 February. He thought that most of the picketing which had taken place was lawful. As regards the criminal law, some arrests had been made but, as he put it, ‘the activities of pickets confronted the police with very difficult and sensitive decisions’.

This was something of an understatement. The left-wing leader of the Yorkshire miners, Arthur Scargill, who was to organize the politically motivated miners’ strike I faced in 1984–85, was already busy winning his militant’s spurs. In the course of Cabinet a message came through to the Home Secretary, Reggie Maudling. The Chief Constable of Birmingham had asked that the West Midlands Gas Board’s Saltley Coke Depot be closed because lorries were being prevented from entering by 7,000 ‘pickets’ who were facing just 500 police.

There was no disguising that this was a victory for violence.

Ted now sounded the retreat. He appointed a Court of Inquiry under the ubiquitous Lord Wilberforce. By now the power crisis had reached such proportions that we sat in Cabinet debating whether we had time to wait for the NUM to ballot its members on ending a strike; a ballot might take over a week to organize. There was therefore no inclination to quibble when Wilberforce recommended a massive pay increase, way beyond the level allowed for in the ‘n-1’ voluntary pay policy already in force.

But we were stunned when the militant majority on the NUM Executive rejected the court’s recommendation, demanding still more money and a ragbag of other concessions.

Ted summoned us all on the evening of Friday 18 February to decide what to do. The dispute simply had to be ended quickly. If we had to go an additional mile, so be it. Later that night Ted called the NUM and the NCB to No. 10 and persuaded the union to drop the demand for more money, while conceding the rest. The NUM Executive accepted, and just over a week later so did the miners in a ballot. The dispute was over. But the devastation it had inflicted on the Government and indeed on British politics as a whole lived on.

The combination of the rise in unemployment, the events at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders and the Government’s humiliation by the miners resulted in a fundamental reassessment of policy. I suspect that this took place in Ted’s own mind first, with other ministers and the Cabinet very much second. It was not so much that he jettisoned the whole Selsdon approach, but rather that he abandoned some aspects of it, emphasized others and added a heavy dose of statism which probably appealed to his temperament and his continental European sympathies.

None of this pleased me. But our inability to resist trade union power was now manifest. The Industrial Relations Act itself already seemed hollow: it was soon to be discredited entirely. Like most Conservatives, I was prepared to give at least a chance to a policy which retained some of the objectives we had set out in 1969/70. I was even prepared to go along with a statutory prices and incomes policy, for a time, to try to limit the damage inflicted by the arrogant misuse of trade union power. But I was wrong. State intervention in the economy is not ultimately an answer to over-mighty vested interests: for it soon comes to collude with them.

It is unusual to hold Cabinets on a Monday, and I had a long-standing scientific engagement for Monday 20 March 1972, so I was not present at the Cabinet which discussed the budget and the new Industry White Paper. Both of them signalled a change in strategy, each complementing the other. The budget was highly reflationary, comprising large cuts in income tax and purchase tax, increased pensions and social security benefits, and extra investment incentives for industry. It was strongly rumoured that Tony Barber and the Treasury were very unhappy with the budget and that it had been imposed on them by Ted. The fact that the budget speech presented these measures as designed to help Britain meet the challenge opened up by membership of the EEC in a small way confirms this. It was openly designed to provide a large boost to demand, which it was argued would not involve a rise in inflation, in conditions of high unemployment and idle resources. Monetary policy was mentioned, but only to stress its ‘flexibility’; no numerical targets for monetary growth were set.

On Wednesday 22 March John Davies published his White Paper on Industry and Regional Development, which was the basis for the 1972 Industry Act. This was seen by our supporters and opponents alike as an obvious U-turn. Keith and I and probably others in the Cabinet were extremely unhappy, and some of this found its way into the press. Should I have resigned? Perhaps so. But those of us who disliked what was happening had not yet worked out an alternative approach. Nor, realistically speaking, would my resignation have made a great deal of difference. I was not senior enough for it to be other than the littlest ‘local difficulty’. All the more reason for me to pay tribute to people like Jock Bruce-Gardyne, John Biffen, Nick Ridley and, of course, Enoch Powell who did expose the folly of what was happening in Commons speeches and newspaper articles.

There is also a direct connection between the policies pursued from March 1972 and the very different approach of my own administration later. A brilliant, but little-known, monetary economist called Alan Walters resigned from the Central Policy Review Staff (CPRS) and delivered not only scathing criticism of the Government’s approach but also accurate predictions of where it would lead.* (#ulink_dd90eac3-f800-5a6e-bd49-70bebd2c690a)

One more blow to the approach we adopted in 1970 had still to fall. This was the effective destruction of the Industrial Relations Act. It had never been envisaged that the Act would result in individual trade unionists going to jail. Of course, no legal provisions can be proof against some remote possibility of that happening if troublemakers are intent on martyrdom. It was a long-running dispute between employers and dockers about ‘containerization’ which provided the occasion for this to happen. In March 1972 the National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) fined the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU) £5,000 for defying an order to grant access to Liverpool Docks. The following month the union was fined £50,000 for contempt on the matter of secondary action at the docks. The TGWU maintained that it was not responsible for the action of its shop stewards, but the NIRC ruled against this in May. Then, out of the blue, the Court of Appeal reversed these judgments and ruled that the TGWU was not responsible, and so the shop stewards themselves were personally liable. This was extremely disturbing, for it opened up the possibility of trade unionists going to jail. The following month three dockers involved in blacking were threatened with arrest for refusing to appear before the NIRC; 35,000 trade unionists were now on strike. At the last moment the Official Solicitor applied to the Court of Appeal to prevent the dockers’ arrest. But then in July another five dockers were jailed for contempt.

The Left were merciless. Ted was shouted down in the House. Sympathetic strikes spread, involving the closure of national newspapers for five days. The TUC called a one-day general strike. On 26 July, however, the House of Lords reversed the Court of Appeal decision and confirmed that unions were accountable for the conduct of their members. The NIRC then released the five dockers.

This was more or less the end of the Industrial Relations Act, though it was not the end of trouble in the docks. A national dock strike ensued and another State of Emergency was declared. This only ended – very much on the dockers’ terms – in August. In September the TUC General Congress rubbed salt into the wound by expelling thirty-two small unions which had refused, against TUC instructions, to de-register under the Act. Having shared to the full the Party’s enthusiasm for the Act, I was appalled.

In the summer of 1972 the third aspect – after reflation and industrial intervention – of the new economic approach was revealed to us. This was the pursuit of an agreement on prices and incomes through ‘tripartite’ talks with the CBI and the TUC. Although there had been no explicit pay policy, we had been living in a world of ‘norms’ since the autumn of 1970 when the ‘n-1’ was formulated in the hope that there would be deceleration from the ‘going rate’ figure in successive pay rounds. The miners’ settlement had breached that policy spectacularly, but Ted drew the conclusion that we should go further rather than go back. From the summer of 1972 a far more elaborate prices and incomes policy was the aim, and more and more the centre of decision-making moved away from Cabinet and Parliament. I can only, therefore, give a partial account of the way in which matters developed. Cabinet simply received reports from Ted on what policies had effectively been decided elsewhere, though individual ministers became increasingly bogged down in the details of shifting and complicated pay negotiations. This almost obsessive interest in the minutiae of pay awards was matched by a large degree of impotence over the deals finally struck. In fact, the most important result was to distract ministers from the big economic issues and blind us with irrelevant data when we should have been looking ahead to the threats which loomed.

The period of the tripartite talks with the TUC and the CBI from early July to the end of October did not get us much further as regards the Government’s aim of controlling inflation by keeping down wage demands. It did, however, move us down other slippery slopes. In exchange for the CBI’s offer to secure ‘voluntary’ price restraint by 200 of Britain’s largest firms, limiting their price increases to 5 per cent during the following year, we embarked on the costly and self-defeating policy of holding nationalized industry price increases to the same level, even though this meant that they continued to make losses. The TUC, for its part, used the role it had been accorded by the tripartite discussions to set out its own alternative economic policy. In flat contradiction to the policies we had been elected to implement, they wanted action to keep down council rents (which would sabotage our Housing Finance Act – intended to bring them closer to market levels). They urged the control of profits, dividends and prices, aimed at securing the redistribution of income and wealth (in other words, the implementation of socialism), and the repeal of the Industrial Relations Act. These demands were taken sufficiently seriously by Ted for him to agree studies of methods by which the pay of low-paid workers could be improved without entailing proportionate increases to other workers. We had, in other words, moved four-square onto the socialist ground that ‘low pay’ – however that might be defined – was a ‘problem’ which it was for government rather than the workings of the market to resolve. In fact, the Government proposed a £2 a week limit on pay increases over the following year, with the CBI agreeing maximum 4 per cent price increases over the same period and the extension of the Government’s ‘target’ of 5 per cent economic growth.

It was not enough. The TUC was not willing – and probably not able – to deliver wage restraint. At the end of October we had a lengthy discussion of the arguments for proceeding to a statutory policy, beginning with a pay freeze. It is an extraordinary comment on the state of mind that we had reached that, as far as I can recall, neither now nor later did anyone at Cabinet raise the objection that this was precisely the policy we had ruled out in our 1970 general election manifesto. Only with the greatest reluctance did Ted accept that the TUC were unpersuadable. And so on Friday 3 November 1972 Cabinet made the fateful decision to introduce a statutory policy beginning with a ninety-day freeze of prices and incomes. No one ever spoke a truer word than Ted when he concluded by warning that we faced a troubled prospect.

The change in economic policy was accompanied by a Cabinet reshuffle. Maurice Macmillan – Harold’s son – had already taken over at Employment from Robert Carr in July 1972, when the latter replaced Reggie Maudling at the Home Office. Ted now promoted his younger disciples. He sent Peter Walker to replace John Davies at the DTI and promoted Jim Prior to be Leader of the House. Geoffrey Howe, an instinctive economic liberal, was brought into the Cabinet but given the poisoned chalice of overseeing prices and incomes policy.

For a growing number of backbenchers the new policy was a U-turn too far. When Enoch Powell asked in the House whether the Prime Minister had ‘taken leave of his senses’, he was publicly cold-shouldered, but many privately agreed with him. Still more significant was the fact that staunch opponents of our policy like Nick Ridley, Jock Bruce-Gardyne and John Biffen were elected to chairmanships or vice-chairmanships of important backbench committees, and Edward du Cann, on the right of the Party and a sworn opponent of Ted, became Chairman of the 1922 Committee.

As the freeze – Stage 1 – came to an end we devised Stage 2. This extended the pay and price freeze until the end of April 1973; for the remainder of 1973 workers could expect £1 a week and 4 per cent, with a maximum pay rise of £250 a year – a formula designed to favour the low-paid. A Pay Board and a Prices Commission were set up to administer the policy. Our backbench critics were more perceptive than most commentators, who considered that all this was a sensible and pragmatic response to trade union irresponsibility. In the early days it seemed that the commentators were right. A challenge to the policy by the gas workers was defeated at the end of March. The miners – as we hoped and expected after their huge increase the previous year – rejected a strike (against the advice of their Executive) in a ballot on 5 April. The number of working days lost because of strikes fell sharply. Unemployment was at its lowest since 1970. Generally, the mood in government grew more relaxed. Ted clearly felt happier wearing his new collectivist hat than he ever had in the disguise of Selsdon.

Our sentiments should have been very different. The effects of the reflationary budget of March 1972 and the loose financial policy it typified were now becoming apparent. The Treasury, at least, had started to worry about the economy, which was growing at a clearly unsustainable rate of well over 5 per cent. The money supply, as measured by M3 (broad money), was growing too fast – though the (narrower) M1, which the Government preferred, less so.* (#ulink_ca0208b4-e5ff-5dd2-a157-7fc95229d726) The March 1973 budget did nothing to cool the overheating and was heavily distorted by the need to keep down prices and charges so as to support the ‘counter-inflation policy’, as the prices and incomes policy was hopefully called. In May modest public expenditure reductions were agreed. But it was too little, and far too late. Although inflation rose during the first six months of 1973, Minimum Lending Rate (MLR) was steadily cut and a temporary mortgage subsidy was introduced. The Prime Minister also ordered that preparations be made to take statutory control of the mortgage rate if the building societies failed to hold it down when the subsidy ended. These fantastic proposals only served to distract us from the need to tackle the growing problem of monetary laxity. Only in July was MLR raised from 7.5 per cent, first to 9 per cent and then to 11.5 per cent. We were actually ahead of Labour in the opinion polls in June 1973, for the first time since 1970. But in July the Liberals took Ely and Ripon from us at by-elections. Economically and politically we had already begun to reap the whirlwind.

Over the summer of 1973 Ted held more talks with the TUC, seeking their agreement to Stage 3. The detailed work was done by a group of ministers chaired by Ted, and the rest of us knew little about it. Nor did I know that close attention was already being given to the problem which might arise with the miners. Like most of my colleagues, I imagine, I believed that they had had their pound of flesh already and would not come back for more.

I hope, though, that I would have given a great deal more attention than anyone seems to have done to building up coal stocks against the eventuality, however remote, of another miners’ strike. The miners either had to be appeased or beaten. Yet, for all its technocratic jargon, this was a government which signally lacked a sense of strategy. Ted apparently felt no need of one since, as we now know, he had held a secret meeting with the miners’ President, Joe Gormley, in the garden of No. 10 and thought he had found a formula to square the miners – extra payment for ‘unsocial hours’. But this proved to be a miscalculation. The miners’ demands could not be accommodated within Stage 3.

In October Cabinet duly endorsed the Stage 3 White Paper. It was immensely complicated and represented the high point – if that is the correct expression – of the Heath Government’s collectivism. All possible eventualities, you might have thought, were catered for. But as experience of past pay policies ought to have demonstrated, you would have been wrong.

My only direct involvement in the working of this new, detailed pay policy was when I attended the relevant Cabinet Economic Sub-Committee, usually chaired by Terence Higgins, a Treasury Minister of State. Even those attracted by the concept of incomes policy on grounds of ‘fairness’ begin to have their doubts when they see its provisions applied to individual cases. My visits to the Higgins Committee were usually necessitated by questions of teachers’ pay.

On one sublime occasion we found ourselves debating the proper rate of pay for MPs’ secretaries. This was the last straw. I said that I hadn’t come into politics to make decisions like this, and that I would pay my secretary what was necessary to keep her. Other ministers agreed. But then, they knew their secretaries; they did not know the other people whose pay they were deciding.

In any case, reality soon started to break in. Two days after the announcement of Stage 3 the NUM rejected an NCB offer worth 16.5 per cent in return for a productivity agreement. The Government immediately took charge of the negotiations. (The days of our ‘not intervening’ had long gone.) Ted met the NUM at No. 10. But no progress was made.

In early November the NUM began an overtime ban. Maurice Macmillan told us that though an early strike ballot seemed unlikely and, if held, would not give the necessary majority for a strike, an overtime ban would cut production sharply. The general feeling in Cabinet was still that the Government could not afford to acquiesce in a breach of the recently introduced pay code. Instead, we should make a special effort to demonstrate what was possible within it. The miners were not the only ones threatening trouble. The firemen, electricians and engineers were all in differing stages of dispute.

Admittedly, the threatened oil embargo and oil price rises resulting from the Arab-Israeli war that autumn made things far worse. As the effects of the miners’ industrial action bit deeper, the sense that we were no longer in control of events deepened. Somehow we had to break out. This made a quick general election increasingly attractive. Quite what we would have done if we had been re-elected is, of course, problematic. Perhaps Ted would have liked to go further towards a managed economy. Others would probably have liked to find a way to pay the miners their Danegeld. Keith and I and a large part of the Parliamentary Conservative Party would have wanted to discard the corporatist and statist trappings with which the Government was now surrounded and try to get back to the free market approach from which we had allowed ourselves to be diverted in early 1972.

At Cabinet on Tuesday 13 November it was all gloom as the crisis accelerated on every front. Tony Barber told us that the October trade figures that day would show another large deficit.

One shrewd move on Ted’s part at the beginning of December was to bring Willie Whitelaw back from Northern Ireland to become Employment Secretary in place of Maurice Macmillan. Willie was both conciliatory and cunning, a combination of qualities particularly necessary if some way were to be found out of the struggle with the miners. The Government’s hand was also strengthened by the fact that, perhaps surprisingly, the opinion polls were now showing us with a clear lead over Labour as the public reacted indignantly to the miners’ actions. In these circumstances, all but the most militant trade unionists would be fearful of a confrontation precipitating a general election.

On Thursday 13 December Ted announced the introduction of a three-day working week to conserve energy. He also gave a broadcast that evening. This gave an impression of crisis which polarized opinion in the country. At first industrial output remained more or less the same, itself an indication of the inefficiency and overmanning of so much of British industry. But we did not know this at the time. Nor could we know how long even a three-day week would be sustainable. I found strong support among Conservatives for the measures taken. There was also understanding of the need for the £1.2 billion public spending cuts, which were announced a few days later.

At this stage we believed that we could rely on business leaders. Shortly before Christmas, Denis and I went to a party at a friend’s house in Lamberhurst. There was a power cut and so night lights had been put in jam jars to guide people up the steps. There was a touch of wartime spirit about it all. The businessmen there were of one mind: ‘Stand up to them. Fight it out. See them off. We can’t go on like this.’ It was all very heartening. For the moment.

There still seemed no honourable or satisfactory way out of the dispute itself. The Government offer of an immediate inquiry into the future of the mining industry and miners’ pay if the NUM went back to work on the basis of the present offer was turned down flat.

It was clear that, if and when we managed to come through the present crisis, fundamental questions would need to be asked about the Government’s direction. The miners, backed in varying degrees by other trade unions and the Labour Party, were flouting the law made by Parliament. The militants were clearly out to bring down the Government and to demonstrate once and for all that Britain could only be governed with the consent of the trade union movement. This was intolerable not just to me as a Conservative Cabinet minister but to millions of others who saw the fundamental liberties of the country under threat. Denis and I, our friends and most of my Party workers, felt that we now had to pick up the gauntlet and that the only way to do that was by calling and winning a general election. From now on, this was what I urged whenever I had the opportunity.

I was, though, surprised and frustrated by Ted Heath’s attitude. He seemed out of touch with reality, still more interested in the future of Stage 3 and in the oil crisis than he was in the pressing question of the survival of the Government. Cabinet discussions concentrated on tactics and details, never the fundamental strategy. Such discussions were perhaps taking place in some other forum; but I rather doubt it. Certainly, there was a strange lack of urgency. I suspect it was because Ted was secretly desperate to avoid an election and did not seriously wish to think about the possibility of one. In the end, perhaps – as some of us speculated – because his inner circle was split on the issue, Ted finally did ask some of us in to see him, in several small groups, on Monday 14 January in his study at No. 10.

By this stage we were only days away from the deadline for calling a 7 February election – the best and most likely ‘early’ date. At No. 10 in our group John Davies and I did most of the talking. We both strongly urged Ted to face up to the fact that we could not have the unions flouting the law and the policies of a democratically elected government in this way. We should have an early election and fight unashamedly on the issue of ‘Who governs Britain?’ Ted said very little. He seemed to have asked us in for form’s sake. I gathered that he did not agree, though he did not say as much. I went away feeling depressed. I still believe that if he had gone to the country earlier we would have scraped in.

The following Wednesday, 30 January, with the strike ballot still pending, an emergency Cabinet was called. Ted told us that the Pay Board’s report on relativities had now been received. The question was whether we should accept the report and set up new machinery to investigate ‘relativities’ claims. The miners had always claimed to be demanding an improvement in their relative pay – hence their rejection of Ted’s ‘unsocial hours’ provision, which applied to all shift workers. The Pay Board report might provide a basis for them to settle within the incomes policy – all the more so because it specifically endorsed the idea that changes in the relative importance of an industry due to ‘external events’ could also be taken into account when deciding pay. The rapidly rising price of oil was just such an ‘external event’.

We felt that the Government had no choice but to set up the relativities machinery. Not to do so – having commissioned the relativities report in the first place – would make it seem as if we were actively trying to prevent a settlement with the miners. And with an election now likely we had to consider public opinion at every step.

An election became all but certain when, on Tuesday 5 February, we learned that 81 per cent of those voting in the NUM ballot had supported a strike. Election speculation reached fever pitch from which there was no going back. Ted told us at Cabinet two days later that he had decided to go to the country. The general election would take place on Thursday 28 February.

Willie proposed formally to refer the miners’ claim to the Pay Board for a relativities study. He couched his argument for this course entirely in terms of it giving us something to say during the election in reply to the inevitable question: How will you solve the miners’ dispute if you win? Cabinet then made the fateful decision to agree to Willie’s proposal.

Because of the emergency nature of the election, I had not been involved in the early drafts of even the education section of the manifesto, which was now published within days. There was little new to say, and the dominant theme of the document – the need for firm and fair government at a time of crisis – was clear and stark. The main new pledge was to change the system whereby Social Security benefits were paid to strikers’ families.

During most of the campaign I was reasonably confident that we would win. Conservative supporters who had been alienated by the U-turns started drifting back to us. Indeed, their very frustrations at what they saw as our past weaknesses made them all the more determined to back us now that we had decided, as they saw it, to stand up to trade union militancy. Harold Wilson set out Labour’s approach in the context of a ‘social contract’ with the unions. Those who longed for a quiet life could be expected to be seduced by that. But I felt that if we could stick to the central issue summed up by the phrase ‘Who governs?’ we would win the argument, and with it the election.