По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

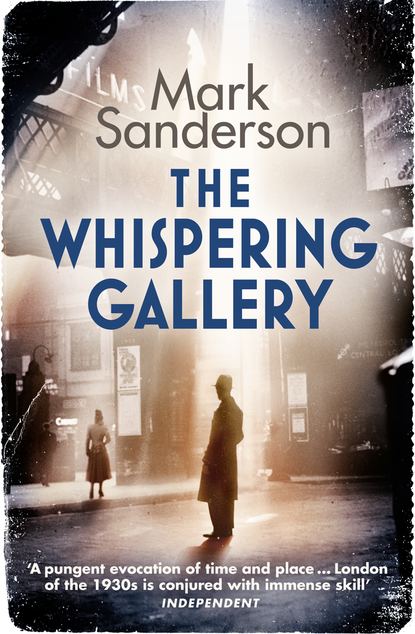

The Whispering Gallery

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Is it okay for me to describe him in my piece? It might prompt someone to come forward.” Johnny held his breath.

“Yes – but I didn’t say that you could. Understood?”

“Of course. Thank you. Have you informed Yapp’s next of kin yet?”

“We’re trying to find out who that is. He was unmarried. Your piece might prove doubly useful.”

“I aim to please. Fancy a drink later?”

“Aren’t you going to see Stella?”

“Why can’t I see both of you?”

“I thought you had something to ask her.”

“I still want to do it in St Paul’s. I’m not going to let what happened stop me.” Some might have chosen to see the accident as an ill omen – but not him. He refused to believe in such nonsense.

“Very well. I’ll be on duty till eight p.m. If I’m not in the Rolling Barrel, I’ll be in the Viaduct.” Matt hung up before he could say anything else.

Instead of replacing the receiver, Johnny dialled the number of The Cock. He knew it off by heart.

“Hello, Mrs Bennion. It’s Johnny. Is Stella there?”

“I’ve told you before: call me Dolly. I thought she was seeing you today.”

“We were due to meet this afternoon but I had to come in to the office. I assumed she’d be back home by now. Perhaps she’s gone shopping.”

“Wouldn’t surprise me.” She lowered her voice. “Did you see Stella last night?”

“No. I haven’t seen her since Thursday. Why?”

“She told us that she was going to visit a friend in Brighton and since she didn’t have to go to work the next day she would spend the night there. Her father took some persuading. He thought you were behind it!”

“Alas, no.” Should he have said that? “So you haven’t heard from her since yesterday?”

“Not a dicky bird.”

“Well, don’t worry. I’m sure she’ll turn up any minute now.”

“I hope so.” She did not sound convinced. Johnny had said the wrong thing: telling people not to worry just served to raise their concern. It was like the dentist, drill in hand, telling you to relax: the very word made you tense up in anticipation of pain.

“I know so. Give my regards to Mr Bennion.”

“I will. He’s having his afternoon nap before the doors open again.” Johnny cursed himself silently. He had probably just woken up his prospective father-inlaw, who already suspected him of whisking off his daughter for a prolonged bout of seaside sex. Now that was inauspicious.

He replaced the receiver and stuck his face in front of the desk-fan. The back of it, which contained the tiny motor, was too hot to touch. The place would probably be cooler if all the fans were turned off.

He should have waited for Stella. What if she hadn’t gone to St Paul’s? Perhaps she had not meant to be late. Something – something bad – could have happened. He crushed the thought. Maybe the beach and the sea breezes had proved too much of a temptation and she had decided to spend the entire weekend away from the stifling City. He wouldn’t blame her if she had.

Stella had never mentioned a pal who lived in Brighton. He’d assumed he’d been introduced to all her friends by now: she’d certainly been introduced to all of his. He enjoyed showing her off, being told that he’d done well for himself, batting away such envious remarks as “Lost her white stick, has she?” Then again, if he had chosen well, so had she. Stella held his heart in her hands. She knew she could count on him.

He checked that the plain gold band was still safely buttoned up in his jacket. It should have been on her finger by now. He sighed in disappointment – but there was no use dwelling on what might have been. He got out his notebook. He had work to do.

It took him less than half an hour. Father Gillespie was unable to furnish him with any further information except the fact that Graham Yapp had been forty-eight. As he bashed out the report, Johnny recalled the other dead man’s expression as he had looked down from the gallery. Even from where he was sitting Johnny could tell it had been one of anticipation rather than fear, of anger rather than regret. And yet his last words had been I’m sorry: an apology for breaking the God-botherer’s neck? A believer was unlikely to have chosen such a place to kill himself.

He handed in his copy to the subs and returned just in time to catch the tea lady. His mother had always said a hot drink was more cooling than a cold one – but only because it encouraged perspiration. He sipped the stewed brew and stared into space. The story was a minor scoop but it had made him a hostage to fortune. If the jumper turned out to have been pushed he would look like an incompetent fool.

He read his messages – there was nothing that couldn’t wait till Monday morning – then turned his attention to the mail.

The two envelopes were the same size but there the similarity ended. The first one was cream-coloured and unsealed. The thick weave of the paper felt pleasurably expensive. It contained a postcard of Saint Anastasia. The martyr, golden-haloed, was draped in red robes. She held a book in one hand and a sprig of palm in the other. A look of ecstasy spread across her pale face. There was a single sentence, carefully inscribed in a swooping hand, on the back:

Beauty is not in the face; beauty is a light in the heart.

There was no signature. He was always getting letters from cranks. To begin with he had kept them in a file along with the threats of grievous bodily harm – or worse – from people who disagreed with what he had written or objected to having their criminal activities exposed in print. Nowadays he just threw them straight in what the public schoolboys, who were everywhere in the City, called the wagger-pagger-bagger. However, he liked the image of the serene saint so he simply put it to one side.

The second envelope, a cheap white one that could have been bought in any stationer’s, was sealed. Wary of paper cuts, he used a ruler to slit it open. An invitation requested his presence at the re-opening of the much-missed Cave of the Golden Calf in Dark House Lane, EC4 on Friday, 9th July from 10 p.m. onwards. A woman, one arm in the air, danced on the left side of the card. Johnny studied the Vorticist design: the way a straight black line and a few jagged triangles conjured up an image of swirling movement, of sheer abandon, was remarkable.

Much-missed? He had never heard of the place. Still, it was intriguing. What was the Cave? A new restaurant? Theatre? Nightclub? There was no telephone number or address to RSVP to, so he would have to turn up to find out. Perhaps Stella would like to go.

Chapter Three (#ulink_fa78157b-4187-53e1-89db-b2177d65bedd)

He hung around for as long as he could, willing the telephone to ring. It didn’t.

Patsel, throwing his considerable weight about as usual, provided a distraction. Bertram Blenkinsopp, a long-serving news correspondent, had written a piece about widespread fears that the groups of Hitler Youth currently on cycling tours of Britain were actually on reconnaissance missions. The smiling teenagers – who looked, at least in the photographs, very smart in their navy blue uniforms of shorts and loose, open-neck tunics – were said to be “spyclists” sent to note down the exact locations of such strategic sites as steelworks and gasworks. Why else would they have visited Sheffield and Glasgow?

However, Patsel, putting the interests of the Fatherland above those of his adopted country, spiked the article – “Where’s the proof?” – and accused Blenkinsopp of producing anti-Fascist propaganda. A stand-up row ensued. The whole newsroom kept their heads down and pretended not to be listening as the irate reporter lambasted his so-called superior:

“You’re not fit to be a journalist. You wouldn’t know a good story if it came up and kicked your fat arse.”

Such exchanges were not uncommon – Patsel had given up complaining to the high-ups; their inaction was widely interpreted as a suggestion that the German should quit before he was interned – but they had become more frequent as the heatwave lengthened and tempers shortened.

The oppressive temperatures only added to the sense of a gathering storm. The “war to end all wars” had been nothing of the sort. It was becoming increasingly obvious each week that diplomacy – or, as Blenkinsopp put it, lily-livered appeasement – had failed and that Britain would soon be at war again.

The argument stopped as suddenly as it had started. Blenkinsopp knew there was nothing he could do: the Hun’s word was final. He stormed off to the pub leaving Patsel pontificating to thin air. Johnny, catching Dimeo’s eye, had to bite the inside of his cheek to stop himself grinning. Blenkinsopp had the right idea: it was time for a beer.

Johnny joined the exodus of office-workers as they poured out into the less than fresh air. The north side of Fleet Street remained in the sun: its dusty flagstones radiated heat. A stench that had recently become all too familiar hung over its drains. Johnny, ignoring the horns of impatient drivers, crossed over into the shade. He still had a couple of hours to kill before he was due to meet Matt.

He lit a cigarette and strolled down to Ludgate Circus, jostled by those keen to get back to their families, gardens or allotments. It was not an evening to go to the pictures. Cinema managers were already complaining about the drop in audiences. On the other hand, the lidos were packed out. People were fighting – literally – to get in.

In Farringdon Street the booksellers were closing up for the day, a few bibliophiles browsing among the barrows until the very moment the potential bargains disappeared beneath ancient tarpaulins. He cut through Bear Alley and came out opposite the Old Bailey.

A crowd of men, beer in hand, sleeves rolled up, blocked the pavement in West Smithfield. It was illegal to drink out of doors but in such weather indulgent coppers would turn a blind eye – in return for a double Scotch. Squeals and shouts came from children playing barefoot in the recreation ground. A couple of them were trying to squirt the others by redirecting the jet of the drinking fountain. There was a palpable sense of relief that the working week was finally over.

The swing doors of The Cock were wedged open. Stella’s father was behind the bar. Johnny perched on a stool and waited for him to finish serving one of his regulars, a retired poulterer who didn’t know what else to do but drink himself to death.

“So she really isn’t with you then?”

Johnny noted the choice of words – isn’t not wasn’t – and shook his head. “Still no word?”