По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

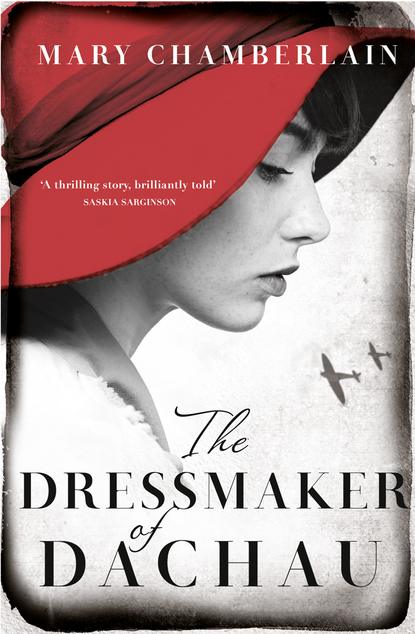

The Dressmaker of Dachau

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She started to answer, but the words tangled in her mouth. Lambeth. Lambeth.

‘No,’ she said. ‘Thank you. I’ll get the bus.’

‘Let me walk you to the stop.’

She wanted to say yes, but she was frightened he’d press her on where she lived. The number 12 went to Dulwich. That was all right. She could say Dulwich, it was respectable enough.

‘You’re hesitating,’ he said. His eyes creased in a smile. ‘Your mother told you never to go with strange men.’

She was grateful for the excuse. His accent was formal. She couldn’t place it.

‘I have a better idea,’ he went on. ‘I’m sure your mother would approve of this.’ He pointed over the road. ‘Would you care to join me, Miss? Tea at the Ritz. Couldn’t be more English.’

What would be the harm in that? If he was up to no good, he wouldn’t waste money at the Ritz. Probably a week’s wages. And it was in public, after all.

‘I am inviting you,’ he said. ‘Please accept.’

He was polite, well-mannered.

‘And the rain will stop in the mean time.’

Ada gathered her senses. ‘Will? Will it? How do you know?’

‘Because,’ he said, ‘I command it to.’ He shut his eyes, stretched his free arm up above his head, raising his umbrella, and clenched and opened his fist three times.

‘Ein, zwei, drei.’

Ada didn’t understand a word but knew they were foreign. ‘Dry?’ she said.

‘Oh, very good,’ he said. ‘I like that. So do you accept?’

He was charming. Whimsical. She liked that word. It made her feel light and carefree. It was a diaphanous word, like a chiffon veil.

Why not? None of the boys she knew would ever dream of asking her to the Ritz.

‘Thank you. I would enjoy that.’

He took her elbow and guided her across the road, through the starlit arches of the Ritz, into the lobby with its crystal chandeliers and porcelain jardinières. She wanted to pause and look, take it all in, but he was walking her fast along the gallery. She could feel her feet floating along the red carpet, past vast windows festooned and ruched in velvet, through marble columns and into a room of mirrors and fountains and gilded curves.

She had never seen anything so vast, so rich, so shiny. She smiled, as if this was something she was used to every day.

‘May I take your coat?’ A waiter in a black suit with a white apron.

‘It’s all right,’ Ada said, ‘I’ll keep it. It’s a bit wet.’

‘Are you sure?’ he said. A sticky ring of heat began to creep up her neck and Ada knew she had blundered. In this world, you handed your clothes to valets and flunkeys and maids.

‘No,’ the words tripped out, ‘you’re right. Please take it. Thank you.’ Wanted to say, don’t lose it, the man in Berwick Street market said it was real camel hair, though Ada’d had her doubts. She shrugged the coat off her shoulders, aware that the waiter in the apron was peeling it from her arms and draping it over his. Aware, too, that the nudge of her shoulders had been slow and graceful.

‘What is your name?’ the man asked.

‘Ada. Ada Vaughan. And yours?’

‘Stanislaus,’ he said. ‘Stanislaus von Lieben.’

A foreigner. She’d never met one. It was – she struggled for the word – exotic.

‘And where does that name come from, when it’s at home?’

‘Hungary,’ he said. ‘Austria-Hungary. When it was an empire.’

Ada had only ever heard of two empires, the British one that oppressed the natives and the Roman one that killed Christ. It was news to her that there were more.

‘I don’t tell many people this,’ he said, leaning towards her. ‘In my own country, I am a count.’

‘Oh my goodness.’ Ada couldn’t help it. A count. ‘Are you really? With a castle, and all?’ She heard how common she sounded. Maybe he wouldn’t notice, being a foreigner.

‘No.’ He smiled. ‘Not every count lives in a castle. Some of us live in more modest circumstances.’

His suit, Ada could tell, was expensive. Wool. Super 200, she wouldn’t be surprised. Grey. Well tailored. Discreet.

‘What language were you talking, earlier, in the street?’

‘My mother tongue,’ he said. ‘German.’

‘German?’ Ada swallowed. Not all Germans are bad, she could hear her father say. Rosa Luxemburg. A martyr. And those who’re standing up to Hitler. Still, Dad wouldn’t like a German speaker in the house. Stop it, Ada. She was getting ahead of herself.

‘And you?’ he said. ‘What were you doing in Dover Street?’

Ada wondered for a moment whether she could say she was visiting her dressmaker, but then thought better of it.

‘I work there,’ she said.

‘How very independent,’ he said. ‘And what do you work at?’

She didn’t like to say she was a tailoress, even if it was bespoke, ladies. Couldn’t claim to be a modiste, like Madame Duchamps, not yet. She said the next best thing.

‘I’m a mannequin, actually.’ Wanted to add, an artiste.

He leant back in the chair. She was aware of how his eyes roamed over her body as if she was a landscape to be admired, or lost in.

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘Of course.’ He pulled out a gold cigarette case from his inside pocket, opened it, and leant forward to Ada. ‘Would you like a cigarette?’

She didn’t smoke. She wasn’t sophisticated like that. She didn’t know what to do. She didn’t want to take one and end up choking. That would be too humiliating. Tea at the Ritz was full of pitfalls, full of reminders of how far she had to go.

‘Not just now, thank you,’ she said.

He tapped the cigarette on the case before he lit it. She heard him inhale and watched as the smoke furled from his nostrils. She would like to be able to do that.