По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

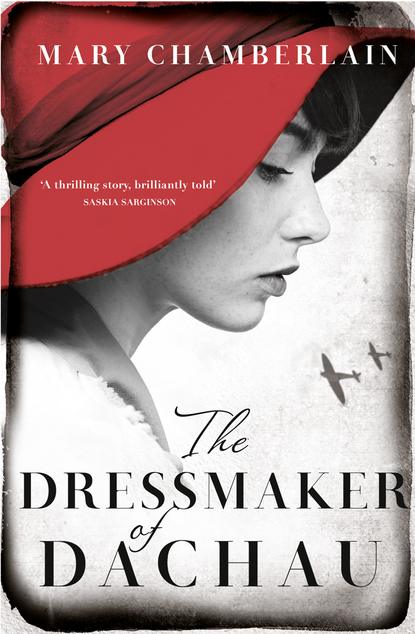

The Dressmaker of Dachau

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘And where are you a mannequin?’

Ada was back on safer ground. ‘At Madame Duchamps.’

‘Madame Duchamps. Of course.’

‘You know her?’

‘My great-aunt used to be a customer of hers. She died last year. Perhaps you knew her?’

‘I haven’t been there very long,’ she said. ‘What was her name?’

Stanislaus laughed and Ada noticed he had a glint of gold in his mouth. ‘I couldn’t tell you,’ he said. ‘She was married so many times, I couldn’t keep up.’

‘Perhaps that’s what killed her,’ she said. ‘All that marrying.’

It would, if her parents were anything to go by. She knew what they would think of Stanislaus and his great-aunt. Morals of a hyena. That was Germany for you. But Ada was intrigued by the idea. A woman, a loose woman. She could smell her perfumed body, see her languid gestures as her body shimmied close and purred for affection.

‘You’re funny,’ Stanislaus said. ‘I like that.’

It had stopped raining by the time they left, but it was dark.

‘I should escort you home,’ he said.

‘There’s no need, really.’

‘It’s the least a gentleman can do.’

‘Another time,’ she said, realizing how forward that sounded. ‘I didn’t mean that. I mean, I have to go somewhere else. I’m not going straight home.’

She hoped he wouldn’t follow her.

‘Another time it is,’ he said. ‘Do you like cocktails, Ada Vaughan? Because the Café Royal is just round the corner and is my favourite place.’

Cocktails. Ada swallowed. She was out of her depth. But she’d learn to swim, she’d pick it up fast.

‘Thank you,’ she said, ‘and thank you for tea.’

‘I know where you work,’ he said. ‘I will drop you a line.’

He clicked his heels, lifted his hat and turned. She watched as he walked back down Piccadilly. She’d tell her parents she was working late.

*

Martinis, Pink Ladies, Mint Juleps. Ada grew to be at ease in the Café Royal, and the Savoy, Smith’s and the Ritz. She bought rayon in the market at trade price and made herself some dresses after work at Mrs B.’s. Cut on the bias, the cheap synthetic fabrics emerged like butterflies from a chrysalis and hugged Ada into evening elegance. Long gloves and a cocktail hat. Ada graced the chicest establishments with confidence.

‘Swept you off your feet, he has,’ Mrs B. would say each Friday as Ada left work to meet Stanislaus. Mrs B. didn’t like gentlemen calling at her shop in case it gave her a bad name, but she saw that Stanislaus dressed well and had class, even if it was foreign class. ‘So be careful.’

Ada twisted rings from silver paper and paraded her left hand in front of the mirror when no one was looking. She saw herself as Stanislaus’s wife, Ada von Lieben. Count and Countess von Lieben. ‘I hope his intentions are honourable,’ Mrs B.’d said. ‘Because I’ve never known a gentleman smitten so fast.’

Ada just laughed.

*

‘Who is he then?’ her mother said. ‘If he was a decent fellow, he’d want to meet your father and me.’

‘I’m late, Mum,’ Ada said. Her mother blocked the hallway, stood in the middle of the passage. She wore Dad’s old socks rolled down to her ankles, and her shabby apron was stained in front.

‘Bad enough you come home in no fit state on a Friday night, but now you’ve taken up going out in the middle of the week, whatever next?’

‘Why shouldn’t I go out of an evening?’

‘You’ll get a name,’ her mother said. ‘That’s why. He’d better not try anything on. No man wants second-hand goods.’

Her mouth set in a scornful line. She nodded as if she knew the world and all its sinful ways.

You know nothing, Ada thought.

‘For goodness sake,’ Ada said. ‘He’s not like that.’

‘Then why don’t you bring him home? Let your father and I be the judge of that.’

He’d never have set foot inside a two-up two-down terrace that rattled when the trains went by, with a scullery tagged on the back and an outside privy. He wouldn’t understand that she had to sleep in the same bed with her sisters, while her brothers lay on mattresses on the floor, the other side of the dividing curtain Dad had rigged up. He wouldn’t know what to do with all those kids running about. Her mother kept the house clean enough but sooty grouts clung to the nets and coated the furniture and sometimes in the summer the bugs were so bad they had to sit outside in the street.

Ada couldn’t picture him here, not ever.

‘I have to go,’ Ada said. ‘Mrs B. will dock my wages.’

Her mother snorted. ‘If you’d come in at a respectable time,’ she said, ‘you wouldn’t be in this state now.’

Ada pushed past her, out into the street.

‘I hope you know what you’re doing,’ her mother yelled for all the neighbours to hear.

*

She had to run to the bus stop, caught the number 12 by the skin of her teeth. She’d had no time for breakfast and her head ached. Mrs B. would wonder what had happened. Ada had never been late for work before, never taken time off. She rushed along Piccadilly. The June day was already hot. It would be another scorcher. Mrs B. should get a fan, cool the shop down so they weren’t all picking pins with sticky fingers.

‘Tell her, Ada,’ one of the other girls said. Poisonous little cow called Avril, common as a brown penny. ‘We’re all sweating like pigs.’

‘Pigs sweat,’ Ada had said. ‘Gentlemen perspire. Ladies glow.’

‘Get you,’ Avril said, sticking her finger under her nose.

Avril could be as catty as she liked. Ada didn’t care. Jealous, most likely. Never trust a woman, her mother used to say. Well, her mother was right on that one. Ada had never found a woman she could call her best friend.

The clock at Fortnum’s began to strike the quarter hour and Ada started to run, but a figure walked out, blocking her way.

‘Thought you were never coming.’ Stanislaus straddled the pavement in front of her, arms stretched wide like an angel. ‘I was about to leave.’