По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

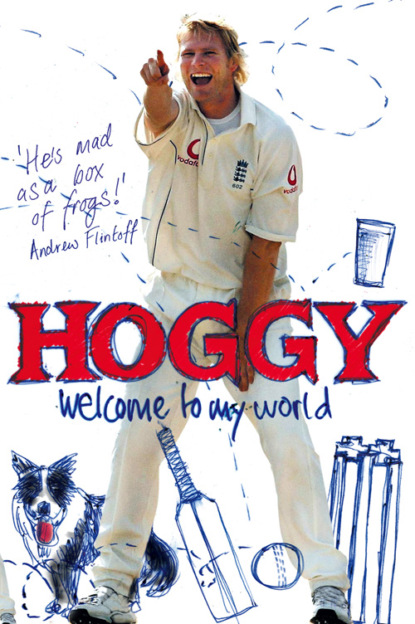

Hoggy: Welcome to My World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Er, yes, I’m afraid it is him. Sorry, Mum.’

So even from that early stage, Sarah was feeling the need to apologise for me. But I’m glad to say that the relationship with my in-laws has progressed considerably since those first days. We get on like a house on fire now and I couldn’t wish for better in-laws. I still regularly play golf with Colin—the Badger, as he has come to be known, because he’s as mad as a badger about his cricket, buying a season ticket for Yorkshire and sitting in the same seat at Headingly all summer. I also still play cricket with Ducey, Sarah’s brother, when I can. As for Carole, I gradually managed to persuade her that I wasn’t always drunk and that I wasn’t quite as rude as she had first thought. I’ve got absolutely no idea what gave her those impressions in the first place, no idea at all. She eventually realised what a fine, upstanding, polite, charming, sober, intelligent individual I was. But it’s a good job that Sarah didn’t listen to her mother’s advice on everything, or I don’t think our relationship would have lasted too long.

† (#ulink_c7479e79-cf8e-5374-b068-d9ad2e6fb381)HOGFACT: By the time they reach the age of SIXTY, most people’s sense of smell is only half as effective as in their younger days. As you can tell by the aftershave that old blokes wear.

† (#ulink_15a650ca-e459-5303-800f-83c6794a00a5)HOGFACT: In Massachusetts, snoring is prohibited unless all bedroom windows are closed and securely locked. I’m led to believe that a man’s punishment for this crime is a slap from the wife.

FIVE GREAT THINGS

ABOUT BEING A

CRICKETER

WORKING CONDITIONS

You don’t have to work in the rain, in the dark, or in the winter: when it gets cold, we just go to a warmer part of the world and play there instead.

REGULAR BREAKS

You get breaks for lunch and tea built into your working day. And breaks for drinks every hour or so as well. Imagine trying to take that many coffee breaks in a normal working day.

LATE STARTS

Our work doesn’t really start until 11 o’clock: okay, we usually have to be at the ground for 9 o’clock, but we don’t really have to be functioning fully until play starts at 11 o’clock.

THE GREAT OUTDOORS

We get to spend all day outside rather than being stuck in an office: a bad day on the cricket field is better than a good day in the office.

SKIVING

Half the time when we’re at work, we don’t actually have to do anything: when your team is batting, you can either sit and chat with your mates or, if necessary, go to sleep on the job. Nice work if you can get it, eh?

PUZZLES

I’ve no doubt that 999,999,999 of my 1,000,000,000 readers will be completely engrossed in the book by now and desperate to get to the next chapter. But just in case you’re the odd one out and feel in need of a break, here are a few puzzles to keep you amused. If you like SuDoku, sorry, I couldn’t draw one of those…

3 Wild and Free (#ulink_e0900b02-4ca0-5d61-9967-1fbcac424b57)

I can remember coming of age clearly, because turning 18 hit me with a thud. The precise moment that the thud occurred was during my 18th birthday party at Pudsey Congs clubhouse (where else?). I was standing on a chair, getting carried away dancing to Cotton-Eyed Joe, and I smashed my head on the fire exit sign. Not quite behaving like a proper grown-up yet, then.

Unsurprisingly, it was Ferg who decided that the time had come for me to broaden my horizons beyond the playing fields of Yorkshire. I’d played my first few games for the county Second XI in the summer of 1995, and not done too badly, but I was still extremely raw, both as a bowler and as a lad.

So Ferg got in touch with Richard Lumb, his old Yorkshire teammate, who had moved out to South Africa and was involved with the Pirates club in Johannesburg. ‘Hoggy, it would do you good to go abroad,’ Ferg said. ‘I’ve sorted you out a club in South Africa, You’ll have a great time. See you in six months.’ And that was pretty much that.

I spent two winters with the Pirates, then returned to South Africa a couple of years later in 1998, a little less raw, for the first of two seasons playing first-class cricket with Free State in Bloemfontein. Both of them were fantastic experiences which, in different ways, helped me to find my way in the world.

My first spell in Johannesburg, shortly after I’d done my A-levels in 1995, was the first time I’d lived away from home. It was also the first time I’d been in an aeroplane. We’d been on umpteen family camping holidays to France when I was younger, but we’d always driven in the car and I’d never been up in the skies. My mum and dad drove me down to Heathrow, and by the time we got to London, I think my fears had gradually given way to excitement. Never mind the six months away from home, I thought, I’m actually going to go up in an aeroplane! Nneeeeeooowwwmmmm!

When I landed at Johannesburg airport, I must have come across like a little boy lost. For what seemed like ages I was looking for Richard Lumb and he was looking for me, both of us without success. He was going round asking anybody with a cricket bag—and there were quite a few—if they were Matthew Hoggard; I was going round looking for a tall bloke with grey hair, and there seemed to be plenty of them as well. Eventually, we found each other and got into his car. We got lost on the drive away from the airport, but he finally managed to take us to the famous Wanderers club, where he set the tone for my trip by buying me lunch and a beer or two.

And that was to become my staple diet for much of my stay in South Africa. Not so much the lunch; just the beer.

I don’t think I’d been warned, by Ferg or anyone else, just how much the South Africans like their beer. They must be the thirstiest nation on earth. Given the chance, they’d have beer for breakfast, and plenty of them do.

Before I’d even played a game with my new team-mates at the Pirates, they took me out to welcome me to the club. We went to the bar at the Randburg Waterfront, a lake just outside Johannesburg with loads of bars and restaurants around it. The evening started with a few convivial drinks, which helped me to relax as I was introduced to these strange people who, like it or lump it, were to become my new friends.

After we’d been in the bar for a couple of hours, I felt myself being shepherded towards the stage. When I was up there, everyone started singing, and I was given a half-pint glass full of the most disgusting-looking green drink. I had no idea what was in it, but something in it had curdled. I later found out that they had gone along the top shelf of spirits and topped up the glass with Coke. Yum yum.

The whole pub was singing at me to down it, so what else could I do? I remember drinking it, but I don’t recall much after that. I just remember waking up in the morning feeling very, very ill. But that had been my initiation ceremony at my new club. Welcome to the Pirates.

The problem was that just about every week seemed to be an initiation. The first game I played was for the club’s second team, so they could have a look at what I was capable of (and perhaps to check that I was still able to bowl a ball in a straight line after my ordeal at the Waterfront). That first game was away from home against Wits Technical College and, in one of those strange coincidences that cricket often throws up, also making his debut for Pirates that day was Gerard Brophy, who a couple of years later would be my captain at Free State and a few years after that came to keep wicket for Yorkshire.

I was quite surprised to find that it was really cold that day. I hadn’t initially planned to pack my cricket jumpers, I just expected it to be baking hot all the time, but I was glad I’d shoved them in at the last minute because it was bloody freezing. Anyway, both Gerard and I did the business on our debuts: he got 100 and I took four wickets.

So the cricket had gone well, but what really got to me was the fines system in the clubhouse afterwards. This was basically an excuse (yet another excuse) for making people drink vast quantities of beer, as decided by the fines-master of the day. Fines would be handed down for stupid comments made during the day, for embarrassing bits of fielding or for any other random transgression that could be deemed punishable by beer. This wasn’t something I’d encountered back at Pudsey Congs. Depending on who the fines-master was for that particular game, the punishment for a brainless comment would probably be to down a bottle of Castle. And that stupid shot you played? Oh yes, you’d better down another bottle for that as well. Needless to say, there was no mercy shown to the newcomers.

The worst offender for each game would be sentenced to death, which meant downing a beer every five minutes. The fines-master would have a watch, and every five minutes a cry of ‘Cuckoo, cuckoo!’ would ring out, signifying that the victim had to stand up and sink another bottle of beer. This would continue for as long as the fines session lasted, sometimes well over an hour. And to thank us for our sterling contributions in our first game for the Pirates, both Gerard and I were sentenced to death that day. So that was Initiation Mark II and another grim hangover the next morning. And there would be plenty more of those to follow.

Throughout my first year in Jo’burg, I stayed with the club chairman, Barry Skjoldhammer (pronounced Shult-hammer) and his family, his wife Nicky, their daughter Kim who was 11, and her brother David, who was 9. I’m not sure they knew what they were letting themselves in for when they agreed to take me in, but they were absolutely fantastic to me and treated me like one of their own. They had a nice house, a games room with a pool table, their own bar and a nice garden with a swimming pool. Life was good. They even took pity on me one morning after I’d come in from a night out at 5.30 a.m. The front door had been bolted and I couldn’t get into the house, so I kicked Sheba, the family dog, out of her bed on the veranda and curled up there for an hour before everyone else woke up. I wasn’t sure what Nicky would say when she found me lying there at 6.30 a.m., but she actually told me off for not waking them up to let me in.

After about three months, the chance came up for me to move out and go to stay in a flat with Alvin Kallicharran, who was also playing club cricket out there. By now, the Skjoldhammers knew that I was a bit wet behind the ears because they said that they wanted me to stay with them so they could keep an eye on me. And no way did I want to go: I got cooked for, I got lifts everywhere, there were kids to play with and they were lovely people. It was great. Even now, I look on the Skjoldhammers as my second family.

It wasn’t just at my new home that I was made to feel welcome. Although it may seem as though they were setting out to kill me with alcohol (I survived more than one death sentence), I couldn’t have been happier with the Pirates.

For a start, we had a very decent team. When they weren’t playing for Transvaal, we had Ken Rutherford, the former New Zealand captain, Mark Rushmere and Steven Jack, who both played for South Africa, and a few guys, like Paul Smith, my fellow opening bowler, who had played for Transvaal.

I also managed to take a few wickets, which helped me to be accepted quickly. It didn’t take me long to adjust my bowling because conditions suited me nicely. We were at altitude in Jo’burg, where the ball tends to swing more in the thinner air, and I was fairly nippy in those days and generally caused a few problems.

It was quite a different club from Pudsey Congs. Back home, I’d been used to there being lots of families around on a weekend. Cricket matches were a family day out on a Saturday and there would always be wives and kids in the clubhouse after the game. Pirates was a bit more spit and sawdust. The wives might come to watch for a while, but the club was mainly frequented by men. For me, that was just part of the learning about a different cricketing and social culture.

There was always a great atmosphere at the club. We used to play our games over two days at a weekend and, as a bowler, there was nothing better than getting your overs out of the way on a Saturday, then turning up on a Sunday morning to watch the batsmen do the hard work, especially as play started at 9 a.m. on the second day.

The Pirates’ ground was in a bowl, so we used to sit up on the banking and start up a scottle braai, a gas barbecue with a flat pan on top, and cook up breakfast for everyone. We’d take it in turns to get the bacon, the eggs, the sausages, and fill our faces with sandwiches while the batsmen went out to do their stuff. I would lose count of the number of times that someone would have just got a sandwich in their hand and a wicket would fall, prompting a distressed cry of: ‘Shit, I was looking forward to that sandwich. Can someone hold onto it for a while?’

I wasn’t paid to play for Pirates and I lived rent-free with the Skjoldhammers, but I did a few odd jobs to pay for my beer money. I helped out at Barry’s Labelpak business, for example, putting together packs of flat-packed furniture, I coached the Pirates kids on a Saturday morning and also did a bit of coaching at Rosemount Primary School during the week. At the school, I remember clipping one irritating lad round the back of the head when he wouldn’t do as I told him. I then got a bit worried when he said: ‘I’m going to go and tell the headmaster you did that.’

Fortunately, the headmaster was Paul Smith, the Pirates’ opening bowler. When the young lad went into the headmaster’s office, he said: ‘Mr Smith, Mr Hoggard just hit me round the back of the head.’ So Smithy hit him round the back of the head himself and said: ‘Well, you must have deserved it then. Now get back to your lesson straight away.’ Good job that wasn’t a few years later. I’d probably have got a lawsuit for doing that nowadays.

The best job I had in Jo’burg was being a barman at the Wanderers’ ground for the big games there. The Pirates had a box and, naturally, they asked me to man the bar. I can’t say it was the most taxing of jobs. I didn’t even have to take cash because there was always some sort of raffle ticket system in operation. I just had to open a few bottles of beer, pour the occasional glass of wine and watch a lot of cricket. And it just so happened that England were touring South Africa that year, so I got to spend a full five days at the second Test when Mike Atherton and Jack Russell staged their famous rearguard action. They certainly worked a lot harder out there than I did up in the bar.

But the important thing about my jobs was that they gave me enough beer money to take advantage of the opportunities for socialising provided by my thoughtful Pirates team-mates. There were plenty of them. Sometimes, I would go out the night before a game with the Smith brothers, Paul and Bruce, and we would put our cricket kit in the car before we went out. That way, we could stay out until the early hours, then drive to wherever we were playing, get a few hours’ kip in the car and wait for our team-mates to wake us up when they arrived. One important part of the procedure was that, before you went to sleep, you had to make sure that your car was under a tree and facing west, so you wouldn’t get burned by the sun when it came up in the morning.

Drink-driving was just not an issue in South Africa in those days. There would be times when we would go on a night out and, while we were driving from one bar to another, everyone would jump out of the car at a red traffic light, run around the car until the lights turned to green, then the one standing nearest the driver’s door had to jump back in and start driving. Everyone else had to squeeze in as well if they could and, if they didn’t, they were left behind. There would be people jumping through windows, hanging onto the roof. We obviously thought it was funny at the time, but it seems like absolute bloody madness now.

Another time when I was out with Bruce Smith, we’d ended up in the Cat’s Pyjamas (nice name), a 24-hour drinking place. For some reason, Bruce suggested we go to the Emmarentia Dam, which was a short drive away. He dared me to swim the 30 metres or so across it, run round a lamppost at the other side, and swim back again. In the clear-sighted wisdom created by God-knows-how-many bottles of Castle lager, I said I’d do it, as long as he did it with me.

We parked up by the dam on an empty side street, took our clothes off in the car and walked to the dam, stark bollock naked. We started swimming across the dam and I was going fairly well, thinking: ‘Yep, this isn’t so bad, I’ll manage it no problem.’ Then it suddenly started thundering and lightning, which made me think we ought to get a move on. We swam across to the other side of the dam, ran round the lamppost and had swum halfway back across the other way when lightning struck the dam. I’ll never forget that feeling when the shock got through to me, sending tingles throughout my body. Even in my less-than-sober state, I was more than a bit worried. ‘Do you feel all right?’ Bruce asked me. ‘Erm, yes, I think so,’ I lied back.