По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

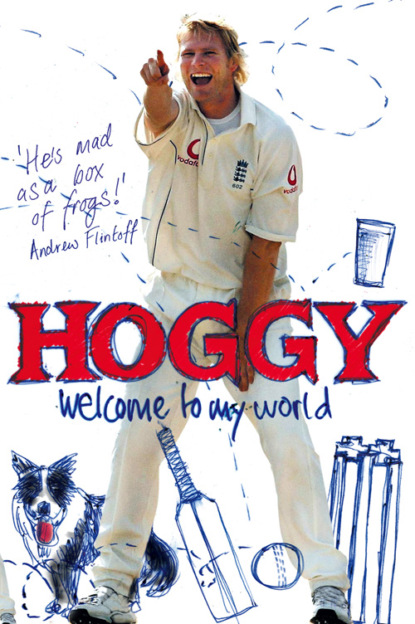

Hoggy: Welcome to My World

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I had a look around the ground and said: ‘Oh, just plonk it on top of that marquee, will you, Boof?’

The next ball was fullish in length. Boof bent down to sweep, put his bottom hand into it and duly deposited the ball on top of the marquee at mid-wicket, as requested.

‘OK, Hog, where shall I put the next one?’ he said. ‘I think I’ll go over mid-on this time.’ Sure enough, Mushy’s next ball disappeared over mid-on, and I started creasing myself as I wandered down the wicket.

‘OK, Boof, what’s next?’ I asked.

‘We’re gonna run two into the covers, OK?’

And you can guess what happened next ball. He called it perfectly. If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I’m not sure I’d have believed it.

And this was against Mushtaq Ahmed, not some second-rate bowler just called up from the second team. I’ve seen plenty of other people try a stunt like this and come a cropper, predicting that the next ball would be a bouncer only to have their middle stump ripped out by a yorker. I might even have been guilty of trying it myself on the odd occasion.

But Boof was different. It was a privilege to play alongside him. And a hell of a giggle.

The winter after we won the championship with Yorkshire, I underwent something of a dramatic transformation as an international bowler. Without so much as playing another game for England, I went from being a novice who had only played two Tests to become the leader of England’s attack. Compared with Jimmy Ormond (one cap), Richard Johnson and Richard Dawson (both uncapped), I was a grizzled, gnarled veteran with the grand total of six Test wickets. We were supported by a couple of all-rounders in Andrew Flintoff and Craig White, but this was hardly an attack to make Sachin Tendulkar toss and turn at night.

This was the tour that came shortly after the 9/11 terrorist atrocities in the US and Andrew Caddick and Robert Croft had opted not to tour. Alec Stewart and Darren Gough had already decided to take the winter off and Mike Atherton had just retired. As a result, we were huge underdogs, there was very little expected of us, but we scrapped and scrapped for everything, and did fairly well to restrict India to a 1-0 win in the three-Test series. Myself and Freddie both did our bit with the ball, and pride was certainly maintained.

This was also the Test series when Phil Carrick’s prediction that VVS Laxman and I, both former team-mates at Pudsey Congs all those years ago, would play each other in a Test match came true. Seven years after he had made it, I was walking onto the outfield at Mohali to warm up for the first Test and I saw Lax having a net with the rest of the Indian lads at the other side of the ground. I looked up to the sky and said: ‘Who’d have thought it, Ferg? You were right.’

Taking on the might of India with a group of spotty youths, we needed a strong and stern headmaster to guide us in the right direction. We had just the man in Mr Nasser Hussain, who did a great job in keeping order in the class. Not that I always saw eye-to-eye with him, and there were a few occasions when I thought I might end up getting the cane. At the end of that first Test in Mohali, we had a massive barney. Or rather, he had a massive barney at me.

We’d been pretty much outplayed throughout that game and our batting had collapsed fairly meekly to 235 all out in the second innings, just avoiding an innings defeat. India then needed only five runs to win, so they opened the batting with Iqbal Siddiqui, a tail-end slogger who had batted at number ten in the first innings.

Nasser didn’t like them doing this. I think he was fairly insulted. As I was opening the bowling, he told me to bounce Siddiqui and make them think twice about doing this sort of thing again. Even though they only wanted five to win, he wanted to show that we were still scrapping.

So Muggins here thought: ‘Bollocks to that, I’m going to try to get him out.’ So I pitched the ball up outside off stump. It was quite a good ball, Siddiqui had a go at it and snicked it through the slips for four. Next ball he clipped one through the leg-side and it was game over.

Back in the dressing-room, I got the biggest bollocking of my life. ‘If I tell you to bowl a f***ing bouncer, I want you to run in and bowl a f***ing bouncer!’ Nasser yelled in my face. ‘You don’t see f***ing McGrath and f***ing Ambrose coming in and bowling piddly half-volleys on leg stump.’ And so it went on. ‘F-this, F-that and F-the F***ing other.’ All of which basically amounted to me getting an almighty bollocking for failing to defend a TARGET OF FIVE.

This happened in front of everybody else in the dressing-room and it made me really upset. When we had to go back out onto the field for the presentation ceremony, I was standing on my own with tears in my eyes. It was my third Test match and I’d just been given the rollicking of my life by the captain when I barely felt that I deserved it. I had people coming up to me and putting their arm round me telling me not to worry about it. But it was a bit late for that.

A couple of hours later, back at the hotel, I was still seething in my room when there was a knock on the door. It was Duncan Fletcher, the coach. I hadn’t had much to do with Fletch up to this point, because he tended to keep himself to himself in the dressing-room and only intervene when he felt it necessary. He clearly felt it necessary this time and said: ‘Don’t take it personally. Nass was just really het up. You didn’t deserve it.’ Half an hour later there was another knock on the door. Nass walked in and gave me a cuddle, told me that he was sorry and walked out again.

Fair enough. That was Nass. He was a very intense, very fiery character, but deep down he can be a really lovely, compassionate guy. When his emotions got the better of him, he could be a complete and utter twat, but I don’t think he ever meant badly. Nass was Nass.

The first time I had encountered his temper had been on that first tour to Pakistan the previous winter. At one of the Test matches, I was one of three or four twelfth men who would take it in turns, session by session, to run errands out onto the field, while the other twelfth men stayed to look after the dressing-room.

On one of the sessions that I was on duty, Nasser had just been dismissed. At the fall of the wicket, I’d done my duty by running down to look after the batsman out in the middle, Mike Atherton, taking him a spare pair of gloves, a drink and some ice. I then went back up to the dressing-room, sat down in my seat and started sending a text message to my missus. (Those were the days when we were still allowed mobile phones in the dressing-room.)

All of a sudden, across the other side of the room, Nasser erupted: ‘I’ll get my own f***ing drink then, shall I?’ he shouted at me. At this time, he was sitting right next to the fridge and could have reached over to open the door himself to get a drink. I was sitting miles† (#ulink_656dc73e-8a97-5095-b642-d25e3b658f87) away from the fridge, presuming that I’d done my duties by attending to Athers. But poor old Nass was a bit upset at getting out and I was in the firing line. I heard a couple of the lads sniggering behind me but didn’t think it wise to join in. I don’t think Nass was in the mood to see the funny side at the time.

So I had plenty of run-ins with Nass because he was a strict disciplinarian as captain and, in those days, I was one of the class clowns. There was one practice day during a one-day series in Zimbabwe when I had taken to making chicken noises all day. I can’t remember why, but I’m sure there was a very sensible, grown-up reason for doing so. For some reason, Nass was getting a bit fed-up of the chicken noises, so he bought Chris Silverwood into the dressing-room and said: ‘Spoons, your job is to keep that twat over there quiet. If I hear any more bird noises out of him. I’m sending the pair of you back to England.’ Spoons and I looked at each other and both started clucking at the top of our voices. Nasser just burst out laughing, shouted, ‘Piss off,’ and legged it out of the dressing-room. Just as well he saw the funny side, really. I wouldn’t have wanted my international career to end for making a few bird noises.

His stricter side was more evident out in the middle. Whenever I bowled a bad ball, I’d turn round to walk back to my mark and see him kicking the dirt at mid-off, which I’m not sure was the most constructive of responses. But Nass did a hell of a lot of good for English cricket while he was captain. He is an immensely passionate person and that rubbed off on a lot of people. His relationship with Fletch was the catalyst for our recovery. They started the consistency of selection that helped to create such a healthy dressing-room environment. Once the older brigade had gone, you wouldn’t just go out with your mates in the same groups for a meal in the evening. Anybody could go out with anybody else.

I think that tour to India, with such a young team, gave Nass and Fletch the opportunity to really stamp their mark on the England team and its culture. And in the longer term we were much better for it.

For the tour that followed to New Zealand in early 2002, we had a couple of older heads back on board and drew the Test series 1-1. The first Test in Christchurch was one of the most bizarre in history, played on a drop-in pitch that seamed about all over the place to start with and then became flatter as the game went on. Nass made a magnificent hundred out of 228, then I got seven for 63 as we skittled them for 147. Nice to have a slightly friendlier pitch to bowl on after slogging away on those dead tracks in India.

We then set New Zealand 550 to win after Thorpey had made a double-century and Fred hit his first hundred, so our victory was just a matter of time. Or so you would have thought.

By now, the pitch was as flat as a fart and Nathan Astle started to chance his arm. The result was that he scored the fastest double-hundred in Test history, hitting sixes left, right and centre. It was a freakish innings. The ball kept going just over someone’s head, or landing just out of somebody else’s reach, but he certainly made the most of his luck.

Chris Cairns had been injured and came in at number eleven—he only came in because they had an outside chance of victory—and when they whittled the target down to fewer than 100 to win, we were feeling seriously jittery. I don’t think we’d have been allowed back to England if we had conceded 550 to lose a Test. Come to think of it, I’m not sure we would have wanted to return. So just when I was wondering whether I would be spending the rest of my life shearing sheep in New Zealand, I managed to get Astle out, caught behind by James Foster off a slower ball. There was a photo in the papers the next day of me celebrating and all the veins looked like they were going to pop out of my neck. We were that relieved.

We may have only drawn the series but I took seventeen wickets in the three Tests and was starting to feel like this Test cricket lark might not be quite so bad after all. As ever with this game, though, you can never make yourself too comfortable. The saying that you are only as good as your last game is one of sport’s biggest clichés, but as an international cricketer it’s something you’re of aware of all the time. You could play like a king one game, but then as soon as you mess up in the next match the first game may as well have never happened. Get ahead of yourself and the game will catch you up and bite you on the bum.

In the first Test of the 2002 English season, against Sri Lanka at Lord’s a couple of months later, I really struggled. I took a couple of wickets, but I went for more than four an over and I was some way short of my best. To make matters worse, before the second Test at Edgbaston I played a Benson & Hedges Cup game for Yorkshire against Essex and got knocked around by Nasser Hussain, of all people, who hit a hundred. Great timing to come up against the England skipper when I was scraping the barrel for anything resembling form.

When I turned up at Edgbaston, my confidence levels were fairly low and Duncan Fletcher knew it. Whether Nass had had a word in his ear or not, I don’t know. In the old changing-rooms at Edgbaston there was a small coach’s office off to one side, and Fletch called me in. ‘Uh-oh,’ I thought. ‘This could be bad news.’

‘Sit down, Hoggy,’ said Fletch. So I did, and held my breath. ‘I just wanted to ask you whether you want to play in this Test match,’ he said.

‘Hell, yes, of course I do, Fletch.’

‘Do you think you are confident enough to play?’

Difficult question to answer. I wasn’t feeling on top of my game and there had been a bit of debate about whether I should hang onto my place. But if you tried to pick and choose your games at international level, waiting until you felt on top form, you’d be no use to anyone.

‘I know I haven’t been at my best in the last couple of weeks, Fletch, but I’m desperate to make it up in this game and, yes, I’ll back myself to do so. I definitely want to play.’

I was lucky at this point that I’d had a good winter in India and New Zealand and this was the time that Fletch was really trying to impose some consistency in the selection. He showed faith in me, gave me another chance and I was extremely chuffed to be able to repay that faith. I took a couple of top-order wickets in the first innings, got 17 not out with the bat, helping Thorpey to add 91 for the last wicket, and then picked up a five-fer in the second innings. We won by an innings and I was named Man of the Match.

I was ecstatically happy after that game, pleased that I’d justified Fletch’s confidence in me and proud that I’d shown the balls to stand up and fight my corner. We had a team meal after the game and then went out to the Living Room in Birmingham. As David Brent would say, ‘El Vino did flow.’

That evening, I was due at my friend Tony Finch’s house on the outskirts of Birmingham for a barbecue. Sarah had gone there to wait for me and Allan Donald was there with Tina, his wife, and their kids. By the time I rocked up in a taxi rather late in the evening, I could barely speak. To get myself to Finchy’s house, I had to ring him up and pass the phone to the taxi driver because I was in no state to pass on directions.

We finally got there and I continued to have a thoroughly marvellous time until it was time to for Sarah and me to go home in a taxi with AD and family. The only memory I have of that journey home is of Hannah, AD’s oldest, saying: ‘Daddy, why has Matthew got his head out of the window?’

AD said, ‘I don’t think he’s feeling too well, Hannah.’

So I was back on track and I then had a decent enough series against India, with the exception of Headingley, where the ball swung all over the place, they got 600-plus and, try as I might, I just couldn’t make Rahul Dravid play. It swung and he left it, time and again.

I had a chat with Fletch about what was going wrong and he suggested that I go wider on the crease, but I wasn’t sure that he was right on this one. At very least, I wanted to try it out for myself, so between Tests I did a bit of work on my bowling with Steve Oldham, the Yorkshire bowling coach whom I respect. I practised quite a bit and, when I got to the Oval for the next Test, I told Fletch that I thought I’d solved my problems. When he watched me bowling, he said: ‘You’re just going wider on the crease. That’s exactly what I told you to do a week ago. Why didn’t you listen to me then?’

That was absolutely fair enough, but I had just wanted to try it out for myself and, before I made a major change in a Test match, to be comfortable and happy in myself that I was doing the right thing. I suppose what it really came down to is that I can be a stubborn sod at times, and Fletch is very stubborn as well, so there were a few occasions when immovable object met immovable object and friction was created as a result.

I played in all seven Tests that summer and I was the leading wicket-taker against both Sri Lanka and India, so I must have done a few things right along the way. And at the end of the season, before we set off for my first Ashes series in Australia, I was awarded a central contract by the ECB. This meant better pay and a workload managed by the England coach. For the first time in my career, my job description was primarily to be an England player, rather than a Yorkshire player who might occasionally play for England. I won’t say that this meant I felt like part of the furniture or settled in the side, but it was at least a bit of evidence that the management had some confidence in my ability. Either that or they just wanted to make sure they could keep a closer eye on me. Whatever the reason, my main bosses were now at Lord’s rather than Headingley, and I didn’t even have to move to London. But it was beginning to look as though I might be a proper England player after all.

† (#ulink_b096f134-3f65-5acc-b2ef-989538fafbb7)HOGFACT: A cough or sneeze makes the AIR in the human respiratory system move faster than the speed of sound. So if someone sneezes right in front of your face, you’ve got to be pretty sharp to get out of the way.

† (#ulink_f8b9e651-0b11-508c-9ee3-f58ba5cdcd70)HOGFACT: The average housewife walks ten MILES a day around the house. I wonder how much of that is walking to the telephone and back to natter to her mother or her friends?

‘Daddy, Daddy, please can I do some words for your book?’

‘Not just yet, Ernie. The nice people want to know all about all the things that Daddy likes to eat that make him big and strong.’