По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

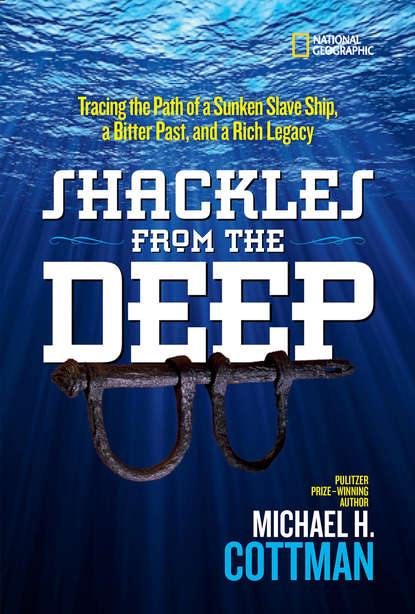

Shackles From the Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 4 (#u0a6213c1-b186-59e2-aacb-868c91edd0c4)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Voyage to Discovery (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading & Other Resources (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments & Photo Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD

by Geoffrey Canada ∼ president of the Harlem Children’s Zone

THESE DAYS, when people talk about slavery in the United States, they think of it as ancient history, but for me it’s not so distant. That’s because I have spoken face-to-face with a slave, my great-grandmother.

She was born just a couple of years before the Emancipation Proclamation, so while she grew up free, she was born into slavery. I only learned about it years after her death, and I was stunned. Suddenly slavery was very real to me. Then something else happened and made me realize slavery is a legacy that’s part of who I am today.

For a segment on the PBS television show Finding Your Roots, historian and Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and his staff did a thorough search of my genetic makeup and my family history. My father had left our family when I was very young, so I had a lot of unanswered questions about my last name and genealogy. Like the characters in the comic books I loved as a young boy, I also wanted to know my “origin story,” to learn what I was made of, what slice of the African-American experience I read about in school was my own. What Gates uncovered was astounding to me.

The researchers dug into old records to see where my father’s surname and family had come from. After some twists and turns, they were finally able to trace the family back to the slave operations of a rural plantation in Virginia run by the Cannady family.

I traveled with Gates to the area where my ancestors were held as slaves. It was disturbing to think of my own flesh and blood living there, people like my great-grandmother, unable to read or write or even know where they were in this strange foreign place. As I walked through the land, surrounded by hills and hearing dogs barking in the distance, I felt in my gut how trapped and frightened my ancestors might have felt there. Even though I now know where my ancestors lived during slavery, I still have so many questions: How long were they there? How were they treated? Did they sail across the Atlantic on a ship like the Henrietta Marie? Sadly that ancestry is untraceable for so many African Americans, who lost their history along with their freedom and dignity.

For me, discovering my own family story highlighted the closeness of history—and that our collective history helps shape us into who we are today.

The Emancipation Proclamation ended the practice of slavery more than 150 years ago, but the tragic legacy of those prior decades continues to cast a long shadow over our present.

Like author Michael Cottman, and the intrepid treasure hunters and marine archaeologists unearthing the wreck of the Henrietta Marie under the sea, it’s critical for all of us to investigate the past—to learn what ground we stand on as we step forward into the future.

TIMELINE OF THE HENRIETTA MARIE

PROLOGUE

“WHERE IS YOUR VILLAGE?” the young girl asked me. It was 1997 and I was traveling through Timbuktu, which is a city in the country of Mali in West Africa.

While there, I met this girl, 10 years old, with brown skin and tiny earrings. She lived on the banks of the Niger River.

She was curious about me. She probably noticed my unusual clothes and correctly concluded that I wasn’t from there.

“I’m from Detroit, in the United States,” I told her.

She paused, then told me that she came from a family of kings and queens, that the men in her tribe were the village elders, and that the women taught young girls to read and write.

“Who are your people?” she asked.

This time I paused. I didn’t really have an answer to her question. I told her about a slave ship called the Henrietta Marie and how I was led to Africa because of this ship. And I told her that we’re all connected through the spirits of our African ancestors regardless of where we live or which villages or towns we come from.

She smiled and whispered to her friends in her West African dialect. I didn’t understand what she was saying, but all of the children smiled and waved to me as I left their village.

Are my people Igbo from Nigeria, or Fulani from Mali, or Wolof from Senegal, or Ashanti from Ghana? Sadly, I may never know. But somehow, as I stood on African soil, I felt at home.

CHAPTER 1

Instruction in youth is like engraving in stone. ∼ Moroccan proverb

I ZIP

UP MY

WET SUIT, adjust my mask, strap on my steel scuba tanks, breathe into my regulator, and slowly descend into a vast underwater world of translucent jellyfish, wide-winged manta rays, and giant sea turtles.

The gentle underwater currents nudge me along the colorful reefs—past the deep purple sea fans, the bursting orange coral heads, and the white tubular anemones that sway in the sea silt.

Bright yellow angelfish swim a few feet above me in synchronized rhythm.