По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

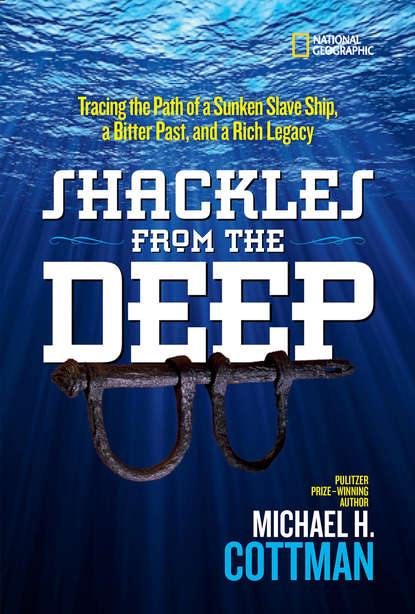

Shackles From the Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It didn’t take long before divers, treasure salvagers, and marine archaeologists were all talking about this mysterious shipwreck without a name. It wasn’t the Nuestra Señora, which Moe would go on to find in 1985. Moe had come across what came to be known only as the “English Wreck.”

The artifacts from the English Wreck were unloaded from the Virgalona and stored in a laboratory in Key West, Florida. Ten years passed, and it seemed the relics with such mystery and importance might be forgotten and lost to time once again.

CHAPTER 3

The future emerges from the past. ∼ Senegalese proverb

WHAT IS

KNOWN AS

THE transatlantic slave trade began in 1441, according to historians, when two Portuguese ships sailed the coast of West Africa. They were looking for gold and other goods in Africa. But they discovered that slavery, the buying and selling of people, could be profitable as well. They knew there was a demand for workers to harvest plantations in the Caribbean and to serve as laborers in Europe and South America.

What began as trading for a few African people ultimately evolved into the centuries-long global kidnapping and exploitation of the West African civilization by European nations, including Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. By the start of the 16th century, according to some historians, tens of thousands of African people had been transported to Europe and islands in the Atlantic Ocean. They were chained inside jam-packed slave ships and would never see Africa—their homeland—again.

The seed of fear was sowed into the fabric of the once vibrant West African villages, generations of African families were torn apart, and life for African men, women, and children would never be the same.

I didn’t know it at the time, but present-day marine archaeologist David Moore was studying the slave trade and had gotten wind of the English Wreck. Because so many shackles were found underwater in a single location, David suspected, like Moe, that New Ground Reef might be the site of a shipwreck that had been part of the 17th-century transatlantic slave trade.

Ten years had passed since Moe Molinar had discovered the shackles from the English Wreck. David was surprised that no one had yet examined the shackles. They felt it was an injustice to let those relics be forgotten and fade away like something swept beneath the carpet of time and history.

He took on a mission to learn everything he could about the English Wreck. He was beginning an amazing journey, and little did I know that I would soon be part of it. David and I believed that to understand our past—the people, cultures, and rationale for slavery—is to also understand ourselves. And so, in some ways, to David archaeology is also about the future and learning from our mistakes.

But David needed more information—a name, a date, a timeline—anything solid that could help him trace the origin of this shipwreck.

For that, David would need to strap on his wet suit and do a little underwater detective work.

BY THE START OF THE 16TH CENTURY, ACCORDING TO SOME HISTORIANS, TENS OF THOUSANDS OF AFRICAN PEOPLE HAD BEEN TRANSPORTED TO EUROPE AND ISLANDS IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN.

CHAPTER 4

Wisdom does not come overnight. ∼ Somali proverb

LATE ONE

AFTERNOON in July 1983, David Moore was aboard the Trident, peeling off his sea-worn wet suit.

For days, David had worked with other divers to survey strategic sections underwater looking for one important yet elusive piece of evidence: the ship’s bronze sailing bell. He assumed that like most ships there would be a bell that would bear the name of the vessel—a vital clue that would help them unravel the mystery of this shadowy shipwreck. They needed this piece to start to put together the puzzle and confirm their theories about the ship’s origins.

David was tired and a bit anxious. But then, as he emerged from the water, he heard one of his crewmates yell: “Hey, you’re not going to believe this. I think we found something big!”

David rushed to the front of the boat, grabbed his dive gear, and stepped into the Gulf of Mexico. The other divers quickly followed.

On the seafloor, one crewmate led the group to an unexplored section of New Ground Reef where, buried in the sand and crusted over, there was a large object. David smiled through his dive mask.

It took a team of three men to hoist the heavy bell onto the Trident and place it in the middle of the deck. After several minutes of staring at the bell in disbelief, everyone started laughing and clapping and high-fiving and reveling in the most significant find from the English Wreck.

The bell was 13 inches high, and two-thirds of it was covered in limestone, which had helped protect it from the salt water.

But David, having studied the history of similar ships, recognized this as a specific kind of bell, a watch bell, which sounds every half hour to signal crew changes aboard a ship. Watches on deck are changed every eight bells.

David reached for a screwdriver (hey, not all archaeology is about delicate brushes and picks) and began to chip away at the thick coating on the bell.

As he scraped the hard, green layers away, a number slowly appeared. A “9.” During the next few minutes, another “9” appeared, and then a “6,” until a full date was showing on the bell: “1699.” Everyone crowded around as David turned the bell around and started scraping the other side.

Slowly, one by one, bold letters began to appear until the crew was able to read the words that were inscribed on the bell:

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: