По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

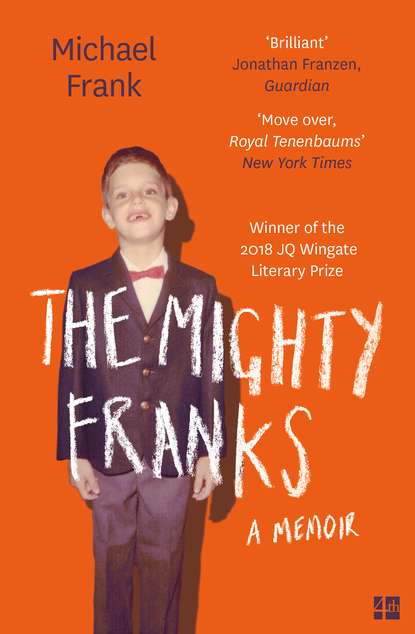

The Mighty Franks: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I don’t understand.”

She put her hand on mine. “He arranged for your grandmother to be cremated.”

I looked at her, confused.

“That means incinerated. Burned instead of buried.”

I shuddered. “All of her?”

“All of her.”

“Has it happened—already?”

“I don’t know the answer to that. He took care of it. The logistics. That’s all I know.”

It was a lot to take in, a lot to put together. “When is the funeral?” I asked.

“Your grandmother didn’t want a funeral. Your aunt doesn’t want one either. And what your aunt wants …” She paused. “Huffy wished to be cremated, and then—then I don’t know what. It’s like she’s still here. I have a feeling it will be like that for a long time.”

If I was so very perceptive, how did I miss so much, how did I miss the central thing?

Was it because I was still just a child? Was it that? Or was it because the central thing had been hidden—purposefully, and with great care—from Huffy herself?

The central thing: this, too, was shared by my two grandmothers.

I had seen Sylvia’s chest deflate—her bra that is, under her dress. And I had seen her reach in to inflate it again, meaning arrange the pad bulked up with crumpled tissues that stood in for her flesh. And I had seen her bra on the hope chest, folded over on itself, its aggregation of padding and tissues peeking out from behind the skin-colored fabric.

No one had ever explained who had taken away a part (two parts) of her body, or why.

What with all that dressing and undressing happening behind closed doors, I had not seen anything equivalent to Sylvia’s deflating chest in Huffy, and nor had I put together all the signs of her changing habits and diminishing energies. What I learned I learned later. The Operation—the mysterious operation that established the ritual of Morning Time—turned out to be a double mastectomy that Huffy had had in October 1965. In 1968 she had a recurrence of the cancer and another surgery, after which the doctor came out from the operating room and told my father, my aunt, and my uncle Peter that he had been unable to remove it all; the disease had spread too far into her body.

“He shook his head,” my mother told me, shaking her own head as she conveyed this scene to me long after the fact. “With that one sentence everything was different … forever different …”

Improbable though it seems now, absurd, really, in view of who this woman was and what her mind and character were like, her children, working in collaboration with the surgeon and our family doctor, agreed—plotted—that very afternoon not to tell my grandmother the truth about herself, about her body, about her body’s fate. Instead they invented a diagnosis, rheumatoid arthritis, that would serve to explain her intermittent pain and weakening and require her to stay in bed for long stretches at a time, like one of her favorite writers, Colette.

For a brief time a stack of Colette’s novels appeared by my grandmother’s bed, in beautiful patterned-paper dust jackets, and my aunt talked about dear, darling Sido—Colette’s mother—and how she and Colette, like Madame de Sévigné and Françoise, were connected in the way that the two Harriets were, beyond mother and daughter, best friends; best friends for all time.

Yet there was something even stranger than this fabrication, this pretend diagnosis that my aunt and my uncle and my father and the doctors devised, and that was the fact that my grandmother went along with it, acting as though she weren’t dying so that her children could act as though she weren’t dying, even though she told a friend of hers, who later told my mother—who was like a great fishing net collecting all the stray, and many of the essential, pieces of information that helped convey the truth of these lives, or a far truer truth than the rest of these people lived by—that Huffy knew perfectly well that the cancer had metastasized and that she was mortally ill.

Everyone was acting, everyone was pretending; too many books had been read, too many movies seen (or conceived, or made). A family that had quite literally written, or story-analyzed, itself into a better, sunnier life, a life where everyone went by new names (and nicknames) and lived in a new or newly done, or redone, house in a new neighborhood in a new city, was unable to write itself out of death. No, not even the Mighty Franks could manage that.

The house filled up with more people.

I went upstairs and changed into a black turtleneck sweater, an article of clothing I wore only when we went skiing. Being unable to cry, I felt I had to find some way to participate, to show people, my aunt above all, that I, too, was upset. When I came downstairs again my mother took one look at me and said, “We don’t dress in black just because someone has died. That’s not who we are or what we do in this family.”

I was ashamed to have been seen through so clearly. I returned to my room and changed back into my school clothes.

I was coming down the stairs again when the doorbell rang. It was Barrie and Wendy, the girls who lived across the street and were our oldest and closest friends. They had come to see if my brothers and I were all right. Their eyes were red and swollen. They called Grandma Huffy “Grandma Huffy” too. But then we were practically related—that’s how we explained it when people asked what we were to each other, since we were so obviously something.

Barrie and Wendy nestled between my brothers and me chronologically, boy-girl-boy-girl-boy, oldest to youngest, tallest to shortest. We sometimes broke down into different pairs and configurations; sometimes we fought with one another, but mostly we adored each other. After school and during the summer, we were often inseparable, playing games and doing art projects and putting on shows together or playing handball or building forts up on the hill—my time with them constituted altogether the most, virtually the only, “normal” time in my childhood.

What practically related us was marriage. Trudy, their aunt, was married to Peter, my father and aunt’s brother and our “outlying” uncle (Herbert was the outlying uncle on my uncle and mother’s side but brought no parallel interlacing into our world); this meant that we had first cousins in common. It was a very Mighty Franks sort of situation and had not come about by accident, either. Trudy had worked as Huffy’s secretary for a time at MGM and had made a good enough impression on my grandmother that when Huffy finally became exasperated by Peter’s taste in women, who inevitably fell short, way short, of The Standard, she invited Trudy to dinner one Sunday and seated her next to her firstborn son. By dessert she had already nicknamed her Beaky, on account of her being tiny, birdlike, and apparently unthreatening, and declared her to be full of clever insights and perceptive conversation. And voilà: this, one of the earliest of my grandmother’s many stabs at matchmaking, became also the most easily realized.

Beaky, it turned out, had a younger brother, Norm, whom Huffy looked up when she traveled to New York on one of her scouting trips for the studio; finding Norm bright and congenial, she convinced him to move to Los Angeles after he finished high school, and she absorbed him, too, into the family, moving him into a spare bedroom for a while until she got him enrolled at UCLA and on his feet. Norm and my father became great friends; after my father moved to Greenvalley Road, he convinced Norm and Linda, his new wife, to move across the street; as before with Aunt Baby, my grandmother’s conjuring yet again expanded and tightened the family weave. And the girls and their parents would have been fully absorbed into our extended family except for one thing: for reasons we never understood, my aunt developed a seething dislike of Norm, Linda, and—especially—the girls. Even on this day of all days, all she had to do for her face to turn black with disapproval was take one look at Barrie and Wendy as they stepped tentatively into the living room to pay a sympathy call.

As the oldest of the five of us kids, I felt very protective of the girls, but there was no way I could shield them from my aunt’s dark look other than trying, and failing, to stand where I could block her view of them and theirs of her.

The girls seemed uncertain whether they should approach Hank or not. They went for not and received an embrace from Trudy, their aunt, instead.

Hank had moved into an armchair. She was no longer rocking back and forth, but then she didn’t have anyone to rock with her. She was still a magnet for everyone’s attention—she had no need for a black turtleneck, or a black anything else. The grief was just pouring off her, like rain. Was grief always like this? My aunt was undergoing a very private experience in a very public setting. Everyone was keeping an eye on her, wondering when she would again erupt. The room was taut with anticipation.

In the armchair she was sitting upright, talking to our family doctor. Her eyes had vanished behind her largest pair of sunglasses. My uncle was standing behind her with one steadying hand resting on her shoulder.

Dr. Derwin said, “I have never had a patient, or known a woman, quite like Senior. It’s hard to think of your family without her …”

From behind my aunt’s sunglasses tears began to shower across her cheeks as a sound formed itself deep in her chest. A moan came up out of her, and another, and soon she was howling again and trembling so violently that she slipped out of the chair. My uncle and the doctor drew in to catch her before she hit the floor.

Barrie came over to me and whispered, “I think we should go now.”

“Maybe you should,” I whispered back.

I walked them out. When I returned, my aunt was back in the chair, but she was still shaking.

In the kitchen my mother was on the phone speaking to Dr. Coleman, our pediatrician. “I don’t think it’s healthy for the children to witness such extreme grief,” she was saying into her hand, which was cupped around the mouthpiece.

Later that night, on Dr. Coleman’s advice, she would dispatch me for several days to the deep Valley, to my cousins. My brothers would be sent elsewhere, to similarly far-removed relatives.

“If you want me out of the house, why can’t I just stay at Barrie and Wendy’s?” I asked when she told me where I was to go.

“It’s not far enough away,” my mother said firmly.

I would never forgive my parents for that, for cutting me off from my own private source of oxygen, which was knowing. Knowing and noting.

My father had not yet come inside. I saw him through the large windows, standing at the edge of the lawn, looking out over the canyon, where daylight was slowly leaking from the sky.

I found Sylvia in the guest room. She was sitting patiently on the sofa, as if she had been waiting for me all this time. I sat down next to her, and she gathered me up in her arms. In her arms I could breathe.

“Are you going to die soon, Grandma?” I asked.

She gave me one of those knowing smiles of hers. “Not soon, my darling,” she said. “No, I’m not.”

“You promise?”

“Yes,” she said, “I promise.”

THREE (#ulink_4552a5e4-83a5-5c03-a936-db85b8afb41c)

ON GREENVALLEY ROAD (#ulink_4552a5e4-83a5-5c03-a936-db85b8afb41c)