По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

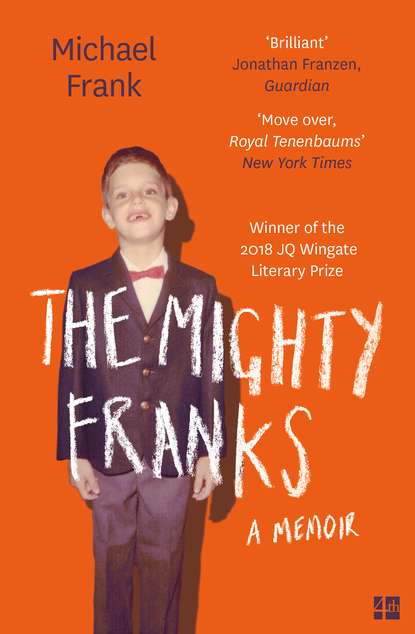

The Mighty Franks: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His wife, naturally. My mother. Who now and then, even in these early days, when she was still the good girl, would introduce a dissenting point of view, a request. That morning, a concern.

“It’s breaking my heart, Marty, to see them treated so differently …”

These weren’t the words that started their argument. They came along somewhere in the middle, after my brothers and I were already listening in.

It started when my father returned from his Sunday tennis game. He was in the kitchen, preparing breakfast. Nothing unusual there. My mother joined him. Not so unusual either. She was always going back downstairs for more coffee. More and more coffee.

What was unusual were the voices, raised so suddenly and to such a decibel that they came up through the floorboards. I was poring over Famous Paintings in my room, my hard-won room of my own, which about a year earlier I had convinced my parents to let me have, arguing that with my reading and drawing and my interest in the visual, and being after all the eldest, it only made sense.

My brothers were in their shared room next door. We came to our respective doorways at the same moment. We looked at one another and then together, in silent agreement, we slipped down the stairs, which were open to the entry hall, which was open to the dining room, which led to the kitchen …

“She’s your sister. You need to speak to her.”

“He’s your brother. Why don’t you speak to him? Go ahead, damn it.”

“She’s the one driving. You know that. She’s the one taking him out nearly every week now, buying him things, never thinking of the other boys. It’s as though they don’t exist. You should have seen their faces. It doesn’t matter what she buys him—the mere fact of it, week after week. It’s breaking my heart, Marty.”

“There is no reaching Hank. You know that.”

There was a pause.

“She told him about your mother and her … exploits. He’s nine years old, for God’s sake. Nine!”

My father was silent.

“You have nothing to say to that?”

“There’s no reaching Hank,” he repeated.

“You don’t try hard enough!”

“I do try! I have tried!”

“Not forcefully enough.”

“I can’t make her do anything. You know her as well as I do. You can’t make that woman—”

“I think you’re afraid to stand up to her. I think you’re afraid, period, of your own sis—”

Loud at his end. High-pitched at hers. I did not need to see my father to know that his nostrils were flaring, his head shaking, as from a tremor.

Our parents had fought before, but not like this. Usually it was in their bedroom, with music on—and turned high. That was our mother’s trick. Crank up the Mamas and the Papas, the children won’t hear. Or they won’t understand if they do.

The children heard. They understood. Their voices, the content. Next: objects. A spatula—a spoon? Had he thrown something? At her? We heard it clattering to the ground.

“I cannot live with this kind of frustration—”

Then we heard a fist, our father’s fist, coming down. Hard. On what? We could not see. Not our mother. Something solid. It sounded like wood.

This sound was followed by another sound: something breaking, then falling to the ground.

There was a pause. A silence. As if even he was surprised at what he had done.

He had banged his fist on the kitchen table. Being an antique—with patina, a story, a treasure brought over from Yurp, all that—it had split in two (we saw the disjointed pieces later, lying there on the floor), scarring the wall as it went down.

“Marty, my God—”

“Don’t you dare—”

“Don’t you say ‘Don’t you dare’—”

My brothers looked at me, the oldest, to do something.

“I’m scared,” whispered Steve.

“So am I,” whispered Danny.

“Get your shoes,” I whispered back. “Come on.”

I could leave a house as stealthily as I could enter it, even with my little brothers following—tiptoeing—down the stairs and out through the glass door in the guest room, then around through the backyard, down the ivy slope, and onto the street.

On the street I noticed that Steve’s shoe was not properly tied. I bent down and knotted it. Double knotted it.

“Is Dad going to hurt Mom?” he asked.

He never had before. He tended to hurt objects, feelings, souls—not people.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I can’t be sure.”

“Where are we going?” Steve asked.

Geographically, Wonderland Park Avenue was a continuation of Greenvalley Road, the reverse side of a loop that wound around the hill the way a string did on its spool; only where Greenvalley was open and sunbaked, Wonderland Park was shady, hidden, mysterious, and at one particular address simply magical. Halfway down the block on the right and bordered by a long row of cypress trees, number 8930 was a formal, symmetrically planned, pale gray stucco house that stood high above its garden (also formal of course, with clipped topiaries and white flowers exclusively) and was so markedly different from all its neighbors that it looked like it had been picked up in Paris and dropped down in Laurel Canyon.

Everything about the house evoked another place, another time, a special sensibility; my aunt’s special sensibility. The curtains in the windows, edged in a brown-and-white Greek meander trim and tied back just so … the crystal chandeliers that even by day winked through the glass and were reflected in tall gilded mirrors … the iron urns out of which English ivy spilled elegantly downward … the eight semicircular steps that drew you up, up, up to the front doors. The doors themselves: tall and made to look like French boiserie, they were punctuated with two brass knobs the size of grapefruit that were so bright and gleaming they seemed to be lit from within.

I led my brothers up the steps and to these doors. Even the doors had their own distinct fragrance, as if they had absorbed and mingled years’ worth of potpourri, bayberry candles, and butcher’s wax and emitted this brew as a kind of prologue to the rooms inside.

I rang the bell. We waited and waited. When I heard the gradually thickening sound of footsteps crossing the long hall (black-and-white checkerboard marble set, always, on the diagonal), I began to feel uneasy for having brought my brothers here, at this time of all times. But where else were we to go?

There was a pause as whoever it was stopped to look, I imagined, through the peephole. Then the left-hand door opened. My aunt, seeing us there, at first lit up. “My darlings, what a surprise.”

It took her a moment to realize that Steve was still in his pajamas. Then she looked, really looked, at our faces. “But what’s wrong?”

“Mom and Dad are having a fight, a terrible, terrible fight,” Danny said, his lower lip turning to Jell-O.

She called back over her shoulder, “Irving—come, come quick.”

Then she knelt down and drew my younger brothers into her arms. “Not to worry, darlings. Everything will be all right.”