По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

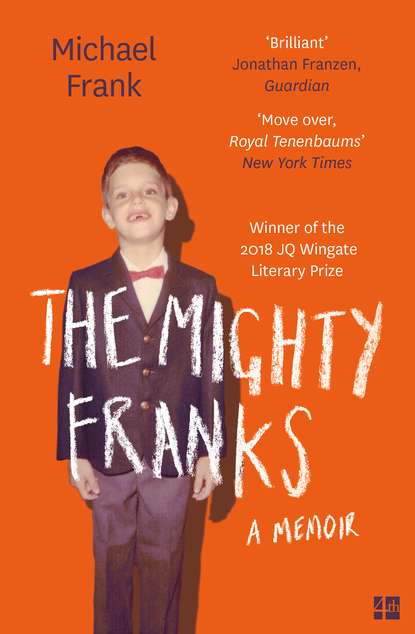

The Mighty Franks: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I put the diary that Grandma Huffy gave me in the drawer of the table by my bed and soon became so absorbed in Famous Paintings, which was my favorite of all the gifts my aunt gave me that weekend, that I was unaware of the door to my room cracking open to allow eyes, two sets of them—my brothers’ two sets—to observe me.

The door cracked, then creaked. I looked up. It opened wider, and first Danny, then Steve, stepped in.

The three of us were graduated in size. I was the tallest and, in these years before adolescence hit, had thick, silky hair that I had recently begun wearing longer over my ears. I had a version of my aunt’s botched nose, though I had been born with mine, which angled off slightly to the left; my eyes were green and often, even then, set within dark black circles that my mother said I had inherited from her father, my rabbi grandfather, but my aunt said were a sign of having an active, curious mind that was difficult to slow down even in sleep. Danny came next in line. His hair, also longer now, had a reddish tinge, and his face looked as if someone had taken an enormous pepper shaker and sprinkled freckles across it. His eyes were not circled in black; instead they went in and out of focus, as if he were intermittently listening to some piece of private music or following a conversation that he had no intention of sharing with anyone, ever. Steve was the “little one”; compact, wiry, athletic (as my aunt often said), he had a sly sense of humor and agate-like gray-green eyes that, even from the doorway, took rapid inventory of the new things on my desk.

“What’re you doing, Mike?” asked Danny.

“Reading,” I said.

“Is that book new?”

I nodded. “It’s a book about art.”

He approached my desk. Steve followed.

“You went to a bookstore without me?” Danny loved bookstores. The books he loved were simply different from the ones I loved. The ones my aunt and uncle and I loved.

I shook my head. “It’s something Auntie Hankie bought for me.”

He shrugged, too casually. “What’s that one?”

“I’m borrowing it from Grandma’s house. It’s a novel. Auntie Hankie read it when she was about my age. It’s for grown-up kids,” I added.

“You’re a grown-up kid?”

When I didn’t answer, Danny moved closer.

“I read novels too, you know.”

“You read science fiction. That’s different.”

“It’s still made-up. It’s still a story,” Danny said.

He picked up the pencil box and asked what it was for. I explained its purpose. I used the words artist, tool of an artist. Patina. Fragile. I said it wasn’t anything he would be interested in. He was the scientist in the family, I reminded him.

The phrase was so expertly parroted I didn’t realize I hadn’t thought it up by myself.

Steve reached over and picked up the box Danny had put down.

“Be careful,” I told him as he opened and closed the lid. “It’s old. It’s not a toy.”

The hinges on the pencil box were fragile. The lid snapped off.

“Sorry,” Steve said. “I didn’t mean to.”

“Sure you didn’t,” I said impatiently.

“I just wanted to see what was inside.”

“I’ll fix it,” I said, grabbing it away from him.

There was another set of eyes at the door now. My mother’s. She took in the scene as much through her pores as through her eyes.

She came in and made her own inventory. Then she looked out the window at the fold of canyon that enclosed our house in a green and brown ravine. The sky overhead was bright and nearly leached of all its color.

“Boys,” she said to my brothers more than to me, “I’ve told you before, I know I have, that things aren’t always equal, with siblings. They can’t be.”

She might not have always looked so carefully at the rest of our house, but in my room just then she was tracking sharply.

“Sometimes it might feel like it’s more unequal than others, but …”

The books, the bookends. The now-damaged pencil box. The pencils. The paper wrapping and bags left from the day’s loot in a hillock on the floor.

“But it all evens out in the end,” she said without much conviction. Without, from what I could tell, much accuracy either.

I found her later in the kitchen before dinner. She was pricking potatoes before putting them into the oven to bake—stabbing them was more accurate.

At dusk, when the lights were on in our kitchen, the window over the sink turned into a mirror. Our eyes met there.

“It’s not my fault if Auntie Hankie likes to buy me things,” I said.

My mother did not turn around to face me. She spoke to the window instead. “I know that,” she said.

She put the potatoes in the oven.

“Or tells me things …”

She closed the oven door. She turned to face me. “What kinds of things?”

I felt my skin redden. But I had started, so I had to finish. Or try to finish. So I repeated to her, as best I could, as best I understood, what my aunt had told me about my grandparents and their marriage.

I felt so … weighted down after that moment in the car. Telling my mother was like taking a huge rock out of my pocket.

My mother’s eyebrows drew close together. “Your aunt is a screenwriter. A dramatist. She is always making up things, making them more—”

“But is it true, what she said?”

With some difficulty my mother regained control of her face. “Not everyone—not every marriage—is like every other,” she said cautiously.

“So it is true, then.”

Her intake of breath made a wheezing sound. “Yes,” she said. “Your grandparents were not—happy together. But there’s no reason for a child to know anything about all that. I don’t know what your aunt was thinking. Really it’s best put out of your mind, Mike. It’s a story for later on.”

My father was a large man, and as different from my uncle as my mother was from my aunt. He had a version of his mother’s forceful, emphatic features, though he was darker and physically more powerful. A former high school football player, he skied and played tennis. He did everything hard. He worked hard at his own medical equipment business. He played sports hard. He chewed his food hard. He trod the stairs with a hard, loud step. When he became ill, which was rare, he became ill hard, spiking outrageous fevers or coming down with stomach bugs that would have landed other men in the hospital. He pruned trees and painted the house hard; he even washed cars hard.

My uncle was softer in every sense. He was brainy, bookish, and gentle. Curious, endlessly curious, about us children. He spoke quietly and with dry humor. He never raised his voice, at least to us, which distinguished him dramatically from my father, who had a terrific, terrifying temper. The Bergman Temper, my mother called it. In our family my father’s temper was assumed to be as elemental, and as unpredictable, as a winter storm. And as natural: he inherited it from his mother; he shared it with his sister and older brother. His rages came on suddenly and were loud and fierce; when he got going there was no reaching him, not ever. “It’s in his genes,” my mother said, trying to explain away what she was powerless to change.

Many different things could set my father off. A dropped egg in the kitchen while he was cooking. An unruly child and (later) an adolescent who gave lip. Traffic. A traffic ticket. Republicans. Criminals. A scratch on the car. A minor loss at gin.