По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

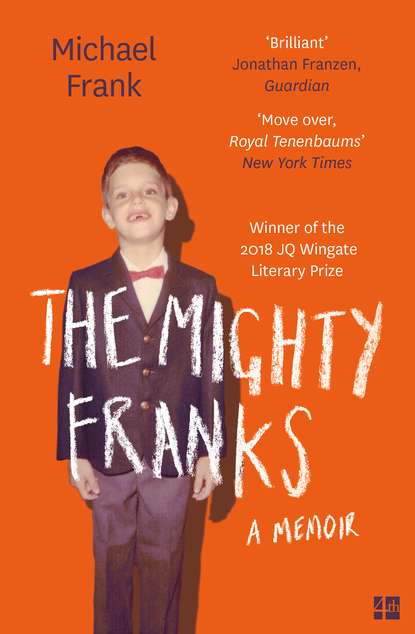

The Mighty Franks: A Memoir

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Make beauty at all times. It’s one of our family tenets, you know.”

“What’s a tenet?”

“A rule you live by. You build your life by.”

“Make beauty. At all times.”

“Yes. In what you draw or paint, in the houses you inhabit. In the way you speak too. And write. And of course be fast about it. Quick-quick. You’ve heard me say that before.”

I nodded.

“There’s plenty of time to sleep in the grave.”

I must have seemed puzzled, because she added, “It means no stopping, no roadblocks allowed. No naps.”

My mother took one every day.

“You must make every moment count,” she went on. “And you must never be afraid to dare. Imagine if Huffy had not dared—imagine if after ten long, horrible years of the Depression in Portland she had not seized the opportunity when Mayer granted her an interview. She piled your father and me and Pups Frank into the Nash and drove straight to Los Angeles, and she knocked the socks off old L.B.M. Everything changed after that. Everything, all of it, everything that makes us the Mighty Franks, comes from that moment, from Huffy, because of her boldness and her courage. Do you understand?”

I shook my head.

“Well, you will. One day. I’ll make sure of that.”

We had glided down out of the canyon. As she turned right onto Laurel Canyon Boulevard, she continued, “Follow your heart wherever it takes you. And always give away whatever possession is most precious to you.”

I looked down at the pages of my new book.

“You mean I have to give this to Danny or Steve one day?”

She cocked her head. “I would say not in this particular case, Lovey. Your brothers’ interests are so markedly different from yours, wouldn’t you agree? Danny—now he is a budding scientist. A logistician. It’s written all over him. He’s going to be a man of facts. I’m as sure of it as I am of my own breath. As for the little one … I see athletics in his future. He’s very skilled physically, just like my brother. Maybe like him he’ll develop a gift for business. Yes, I’m sure he will. We need that in the family, do we not? As a kind of ballast. It’s only practical. Literature, though? Art, architecture? The creative in any and all forms of expression? That’s your purview.”

Purview was like tenet, but I didn’t have to ask. “It means area of expertise. Strength.” She gestured at the book. “No, this one is earmarked for you. As is so much more.”

So much more what? I wondered. As if she could read my mind, my aunt added, “A collector does not spend a lifetime assembling beautiful things merely to have them scattered after she’s gone.”

She turned her face toward me. In her eyes there was that familiar sparkle. It blazed for a moment as she smiled at me, then drove on.

At Hollywood Boulevard we veered left onto a stretch of road that was wholly residential and lined, on the uphill side, with a series of houses that my aunt had previously taught me to identify. Moorish. Tudor. Spanish. Craftsman. Every time I watched these houses flash by the car window I wondered how they could be so different, one from the other, and yet stand next to one another all in an obedient row. Entire streets, entire neighborhoods, were like that in L.A.: mismatched and fantastical, dreamed-up houses for a dreamscape of a city.

At Ogden Drive we turned right, as we always did, and my aunt pulled up in front of number 1648. The Apartment. That is simply how it was known to us: The Apartment. We’re stopping by The Apartment. They need us at The Apartment. Your birthday this year will be at The Apartment. There has been some very bad news at The Apartment.

She never taught me to identify the style of The Apartment, but that was probably because it didn’t have one, particularly. A stucco building from the 1930s, it wrapped around an interior courtyard that was lushly planted with camellias and gardenias and birds-of-paradise, but what mattered most about The Apartment was that, for many years, since well before I was born, my two grandmothers had lived there—together.

“Quick-quick,” my aunt said as she turned off the ignition. “We’re nearly ten minutes late for Morning Time. Huffy will be worried to death.”

Huffy—the older of my two grandmothers, the mother of my aunt and my father—was sitting up in bed, reading calmly, when we hurried into her room. She was in the bed closest to the door. The two beds were a matched pair whose head- and footboards were capped with gold-painted, flame-shaped finials. She looked like she was riding in a boat, a gilded boat that was bobbing in a sea of embossed pink and white urns and wreaths that were papered onto the walls.

“I’m sorry we’re late, Mamma,” my aunt said. “Mike and I were engaged in rapt conversation, and I lost track of the time.”

My grandmother’s hair had come loose in the night, and she wasn’t wearing any makeup, but with her erect posture and her dark focused eyes she still, somehow, seemed alert and all-seeing. “It’s Saturday,” she said as she removed her reading glasses. “Today is the one day you are meant to slow down, my darling. I’ve told you that before.”

“There’s plenty of time to slow down in—” my aunt started to say. “Anyway we’re here now.”

“Is the boy going to noodle around with us this morning?” my grandmother asked.

My aunt smiled at me. “We need his eye, don’t we?”

“He does have a good one,” said my grandmother.

“Of course he does. I trained him myself.”

Morning Time was the sacred hour or so during which my aunt brushed her mother’s hair, wound it into a perfect bun, and pinned it to the top of her head before helping her put on her makeup and her clothes. Afterward she made my grandmother breakfast and sat nearby while my grandmother ate, so that they could visit before my aunt drove back up the hill and (on weekdays) sat down with my uncle to write.

This ritual went back to before I was conscious. It began when my grandmother had The Operation—never further detailed or explained—after which, for a while, she needed help dressing and doing up her hair. It had long since evolved into the routine with which the two women began their days, seven days a week without exception.

During the first part of Morning Time, the grooming and dressing part, I was always sent to wait in the living room. Often, as on this morning, I waited until my aunt had closed the door behind me, then I slipped down the hall to Sylvia’s room. Sylvia was my “other” grandmother, Merona and Irving’s mother.

Her door was closed, as usual. I pressed my ear to it, then knocked.

“Michaelah?”

I opened the door just wide enough to fit myself through, then I closed it again. “I wasn’t even sure you were here,” I said.

“I don’t like to be in Hankie’s way when she’s making breakfast.”

“What about yours?” I asked.

“Later,” she said with a shrug.

She was sitting on the corner of her bed, fully dressed, a folded newspaper in her lap. Her room was half the size of Huffy’s, and had no grand headboard with leaping gold flames. The bed was the only place in the room to sit other than a low, hard cedar hope chest.

Besides the hope chest, there was a high dresser on top of which stood several photographs of Sylvia’s husband, my striking-looking rabbi grandfather who died before I was born; these pictures were the only thing in the entire room—the entire apartment—that was personal to Sylvia, other than the radio by the bed, which was tuned to a near whisper and always to the local classical station.

“Are you coming out with us this morning?” I asked.

Sylvia’s head fell to an angle. It was as though my grandmother—my second grandmother, as I thought of her—was always assessing, or taking careful measure, before she spoke or acted.

“I think not—today.”

Physically Sylvia was smaller and shorter than Huffy, as my mother was smaller and shorter than my aunt; even her nose and eyes were smaller, more delicate and tentative. Dimmer too, you might say, except that they missed very little.

These small noting eyes of hers peered down the hall, or where the hall would have been visible if the door had been open.

“Maybe next week,” she added.

I knew she was lying. She knew I knew she was lying. We’d had a version of this conversation many Saturdays before.

“Monday I’m on the hill,” she said, meaning at our house on Greenvalley Road, where she could cook in our kitchen and eat kumquats off the tree and read in the garden under the Japanese elm in the backyard and let the vigilance drain out of those small eyes. “I’ll make tapioca.”