По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

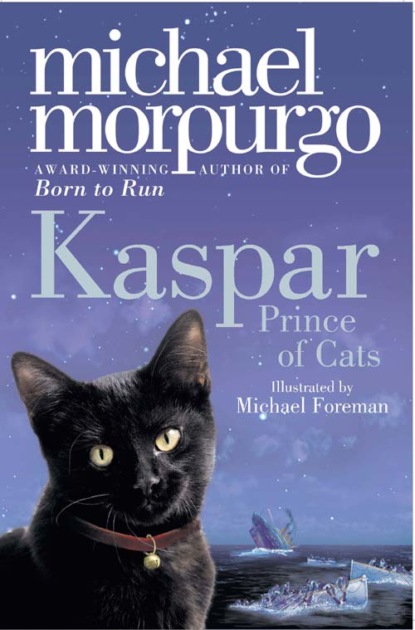

Kaspar: Prince of Cats

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Kaspar: Prince of Cats

Michael Morpurgo

Michael Foreman

Discover the beautiful stories of Michael Morpurgo, author of Warhorse and the nation’s favourite storytellerA heart-warming novel about Kaspar the Savoy cat, from the award-winning author of Born to Run and The Amazing Story of Adolphus TipsKaspar the cat first came to the Savoy Hotel in a basket – Johnny Trott knows, because he was the one who carried him in. Johnny was a bell-boy, you see, and he carried all of Countess Kandinsky's things to her room.But Johnny didn't expect to end up with Kaspar on his hands forever, and nor did he count on making friends with Lizziebeth, a spirited American heiress. Pretty soon, events are set in motion that will take Johnny – and Kaspar – all around the world, surviving theft, shipwreck and rooftop rescues along the way. Because everything changes with a cat like Kaspar around. After all, he's Prince Kaspar Kandinsky, Prince of Cats, a Muscovite, a Londoner and a New Yorker, and as far as anyone knows, the only cat to survive the sinking of the Titanic…

Copyright (#ulink_2606f83f-146c-564c-817e-e2cdbd2e2db6)

HarperCollins Children’s Books An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Michael Morpurgo 2008. Illustrations copyright © Michael Forman 2008

Cover photographs © Masterfile (cat); Shutterstock (sea and sky). Illustrations by Michael Foreman. Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2009.

Micahel Morpurgo asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007267002

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007385935

Version: 2016-11-02

For all the good and kind people at The Savoy who looked after us so well.

MM.

For my brother Pud, a North Sea fisher-man and boy.

MF.

Contents

Cover Page (#u892bd968-5ca4-518a-9e85-c64edbdf0214)

Title Page (#u89ff5909-52d0-5c9b-99fe-530bafb4f159)

Copyright (#ua38a6b13-2519-5065-9e9f-f356c2602d26)

Dedication (#u35bb1604-c33c-577c-8e29-8696cf5b8e21)

The Coming of Kaspar (#u2f9a4a61-5072-532e-b57d-ec813c4f44ad)

Not Johnny Trott at All (#ueb1ba442-0112-59fb-b1ad-a1de7e2bfa57)

A Ghost in the Mirror (#udd7c3511-1f4e-50f4-adb3-8baefeea37cf)

“Who Gives a Fig, Anyway?” (#litres_trial_promo)

Running Wild (#litres_trial_promo)

Stowaway (#litres_trial_promo)

“We’ve Only Gone and Hit A Flaming Iceberg” (#litres_trial_promo)

Women and Children First (#litres_trial_promo)

“Good Luck and God Bless You” (#litres_trial_promo)

A New Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Michael Morpurgo (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Coming of Kaspar (#ulink_9814445e-cdf1-5a8a-b3b7-f3602a3e30e2)

Prince Kaspar Kandinsky first came to the Savoy Hotel in a basket. I know because I was the one who carried him in. I carried all the Countess’ luggage that morning, and I can tell you, she had an awful lot of it.

But I was a bell-boy so that was my job: to carry luggage, to open doors, to say good morning to every guest I met, to see to their every need, from polishing their boots to bringing them their telegrams. In whatever I did I had to smile at them very politely, but the smile had to be more respectful than friendly. And I had to remember all their names and titles too, which was not at all easy, because there were always new guests arriving. Most importantly though, as a bell-boy – which, by the way, was just about the lowest of the low at the hotel – I had to do whatever the guests asked me to, and right away. In fact I was at almost everyone’s beck and call. It was “jump to it, Johnny”, or “be sharp about it, boy”, do this “lickedysplit”, do that “jaldi, jaldi”. They’d click their fingers at me, and I’d jump to it lickedysplit, I can tell you, particularly if Mrs Blaise, the head housekeeper, was on the prowl.

We could always hear her coming, because she rattled like a skeleton on the move. This was on account of the huge bunch of keys that hung from her waist. She had a voice as loud as a trombone when she was angry, and she was often angry. We lived in constant fear of her. Mrs Blaise liked to be called “Madame”, but on the servants corridor at the top of the hotel where we all lived – bell-boys, chamber maids, kitchen staff – we all called her Skullface, because she didn’t just rattle like a skeleton, she looked a lot like one too. We did our very best to keep out of her way.

To her any misdemeanour, however minor, was a dreadful crime – slouching, untidy hair, dirty fingernails. Yawning on duty was the worst crime of all. And that’s just what Skullface had caught me doing that morning just before the Countess arrived. She’d just come up to me in the lobby, hissing menacingly as she passed, “I saw that yawn, young scallywag. And your cap is set too jaunty. You know how I hate a jaunty cap. Fix it. Yawn again, and I’ll have your guts for garters.”

I was just fixing my cap when I saw the doorman, Mr Freddie, showing the Countess in. Mr Freddie clicked his fingers at me, and that was how moments later I found myself walking through the hotel lobby alongside the Countess, carrying her cat basket, with the cat yowling so loudly that soon everyone was staring at us. This cat did not yowl like other cats, it was more like a wailing lament, almost human in its tremulous tunefulness. The Countess, with me at her side, swept up to the reception desk and announced herself in a heavy foreign accent – a Russian accent, as I was soon to find out. “I am Countess Kandinsky,” she said. “You have a suite of rooms for Kaspar and me, I think. There must be river outside my window, and I must have a piano. I sent you a telegram with all my requirements.”

The Countess spoke as if she was used to people listening, as if she was used to being obeyed. There were many such people who came in through the doors of the Savoy: the rich, the famous and the infamous, business magnates, lords and ladies, even Prime Ministers and Presidents. I don’t mind admitting that I never much cared for their haughtiness and their arrogance. But I learned very soon, that if I hid my feelings well enough behind my smile, if I played my cards right, some of them could give very big tips, particularly the Americans. “Just smile and wag your tail.” That’s what Mr Freddie told me to do. He’d been working at the Savoy as a doorman for close on twenty years, so he knew a thing or two. It was good advice. However the guests treated me, I learned to smile back and behave like a willing puppy dog.

That first time I met Countess Kandinsky I thought she was just another rich aristocrat. But there was something I admired about her from the start. She didn’t just walk to the lift, she sailed there, magnificently, her skirts rustling in her wake, the white ostrich feathers in her hat wafting out behind her, like pennants in a breeze. Everyone – including Skullface, I’m glad to say – was bobbing curtsies or bowing heads as we passed by, and all the time I found myself basking unashamedly in the Countess’ aura, in her grace and grandeur.

I felt suddenly centre stage and very important. As a fourteen-year-old bell-boy, abandoned as an infant on the steps of an orphanage in Islington, I had not had many opportunities to feel so important. So by the time we all got into the lift, the Countess and myself and the cat still wailing in its basket, I was feeling cock-a-hoop. I suppose it must have showed.

“Why are you smiling like this?” The Countess frowned at me, ostrich feathers shaking as she spoke.

I could hardly tell her the truth, so I had to think fast. “Because of your cat, Countess,” I replied. “She sounds funny.”

Michael Morpurgo

Michael Foreman

Discover the beautiful stories of Michael Morpurgo, author of Warhorse and the nation’s favourite storytellerA heart-warming novel about Kaspar the Savoy cat, from the award-winning author of Born to Run and The Amazing Story of Adolphus TipsKaspar the cat first came to the Savoy Hotel in a basket – Johnny Trott knows, because he was the one who carried him in. Johnny was a bell-boy, you see, and he carried all of Countess Kandinsky's things to her room.But Johnny didn't expect to end up with Kaspar on his hands forever, and nor did he count on making friends with Lizziebeth, a spirited American heiress. Pretty soon, events are set in motion that will take Johnny – and Kaspar – all around the world, surviving theft, shipwreck and rooftop rescues along the way. Because everything changes with a cat like Kaspar around. After all, he's Prince Kaspar Kandinsky, Prince of Cats, a Muscovite, a Londoner and a New Yorker, and as far as anyone knows, the only cat to survive the sinking of the Titanic…

Copyright (#ulink_2606f83f-146c-564c-817e-e2cdbd2e2db6)

HarperCollins Children’s Books An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Michael Morpurgo 2008. Illustrations copyright © Michael Forman 2008

Cover photographs © Masterfile (cat); Shutterstock (sea and sky). Illustrations by Michael Foreman. Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2009.

Micahel Morpurgo asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007267002

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007385935

Version: 2016-11-02

For all the good and kind people at The Savoy who looked after us so well.

MM.

For my brother Pud, a North Sea fisher-man and boy.

MF.

Contents

Cover Page (#u892bd968-5ca4-518a-9e85-c64edbdf0214)

Title Page (#u89ff5909-52d0-5c9b-99fe-530bafb4f159)

Copyright (#ua38a6b13-2519-5065-9e9f-f356c2602d26)

Dedication (#u35bb1604-c33c-577c-8e29-8696cf5b8e21)

The Coming of Kaspar (#u2f9a4a61-5072-532e-b57d-ec813c4f44ad)

Not Johnny Trott at All (#ueb1ba442-0112-59fb-b1ad-a1de7e2bfa57)

A Ghost in the Mirror (#udd7c3511-1f4e-50f4-adb3-8baefeea37cf)

“Who Gives a Fig, Anyway?” (#litres_trial_promo)

Running Wild (#litres_trial_promo)

Stowaway (#litres_trial_promo)

“We’ve Only Gone and Hit A Flaming Iceberg” (#litres_trial_promo)

Women and Children First (#litres_trial_promo)

“Good Luck and God Bless You” (#litres_trial_promo)

A New Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Michael Morpurgo (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Coming of Kaspar (#ulink_9814445e-cdf1-5a8a-b3b7-f3602a3e30e2)

Prince Kaspar Kandinsky first came to the Savoy Hotel in a basket. I know because I was the one who carried him in. I carried all the Countess’ luggage that morning, and I can tell you, she had an awful lot of it.

But I was a bell-boy so that was my job: to carry luggage, to open doors, to say good morning to every guest I met, to see to their every need, from polishing their boots to bringing them their telegrams. In whatever I did I had to smile at them very politely, but the smile had to be more respectful than friendly. And I had to remember all their names and titles too, which was not at all easy, because there were always new guests arriving. Most importantly though, as a bell-boy – which, by the way, was just about the lowest of the low at the hotel – I had to do whatever the guests asked me to, and right away. In fact I was at almost everyone’s beck and call. It was “jump to it, Johnny”, or “be sharp about it, boy”, do this “lickedysplit”, do that “jaldi, jaldi”. They’d click their fingers at me, and I’d jump to it lickedysplit, I can tell you, particularly if Mrs Blaise, the head housekeeper, was on the prowl.

We could always hear her coming, because she rattled like a skeleton on the move. This was on account of the huge bunch of keys that hung from her waist. She had a voice as loud as a trombone when she was angry, and she was often angry. We lived in constant fear of her. Mrs Blaise liked to be called “Madame”, but on the servants corridor at the top of the hotel where we all lived – bell-boys, chamber maids, kitchen staff – we all called her Skullface, because she didn’t just rattle like a skeleton, she looked a lot like one too. We did our very best to keep out of her way.

To her any misdemeanour, however minor, was a dreadful crime – slouching, untidy hair, dirty fingernails. Yawning on duty was the worst crime of all. And that’s just what Skullface had caught me doing that morning just before the Countess arrived. She’d just come up to me in the lobby, hissing menacingly as she passed, “I saw that yawn, young scallywag. And your cap is set too jaunty. You know how I hate a jaunty cap. Fix it. Yawn again, and I’ll have your guts for garters.”

I was just fixing my cap when I saw the doorman, Mr Freddie, showing the Countess in. Mr Freddie clicked his fingers at me, and that was how moments later I found myself walking through the hotel lobby alongside the Countess, carrying her cat basket, with the cat yowling so loudly that soon everyone was staring at us. This cat did not yowl like other cats, it was more like a wailing lament, almost human in its tremulous tunefulness. The Countess, with me at her side, swept up to the reception desk and announced herself in a heavy foreign accent – a Russian accent, as I was soon to find out. “I am Countess Kandinsky,” she said. “You have a suite of rooms for Kaspar and me, I think. There must be river outside my window, and I must have a piano. I sent you a telegram with all my requirements.”

The Countess spoke as if she was used to people listening, as if she was used to being obeyed. There were many such people who came in through the doors of the Savoy: the rich, the famous and the infamous, business magnates, lords and ladies, even Prime Ministers and Presidents. I don’t mind admitting that I never much cared for their haughtiness and their arrogance. But I learned very soon, that if I hid my feelings well enough behind my smile, if I played my cards right, some of them could give very big tips, particularly the Americans. “Just smile and wag your tail.” That’s what Mr Freddie told me to do. He’d been working at the Savoy as a doorman for close on twenty years, so he knew a thing or two. It was good advice. However the guests treated me, I learned to smile back and behave like a willing puppy dog.

That first time I met Countess Kandinsky I thought she was just another rich aristocrat. But there was something I admired about her from the start. She didn’t just walk to the lift, she sailed there, magnificently, her skirts rustling in her wake, the white ostrich feathers in her hat wafting out behind her, like pennants in a breeze. Everyone – including Skullface, I’m glad to say – was bobbing curtsies or bowing heads as we passed by, and all the time I found myself basking unashamedly in the Countess’ aura, in her grace and grandeur.

I felt suddenly centre stage and very important. As a fourteen-year-old bell-boy, abandoned as an infant on the steps of an orphanage in Islington, I had not had many opportunities to feel so important. So by the time we all got into the lift, the Countess and myself and the cat still wailing in its basket, I was feeling cock-a-hoop. I suppose it must have showed.

“Why are you smiling like this?” The Countess frowned at me, ostrich feathers shaking as she spoke.

I could hardly tell her the truth, so I had to think fast. “Because of your cat, Countess,” I replied. “She sounds funny.”