По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

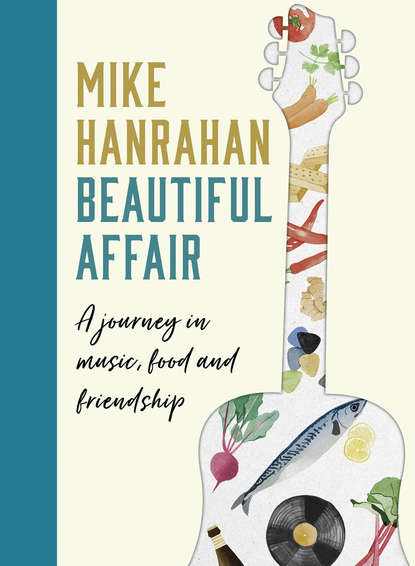

Beautiful Affair

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Once a week they travelled to Ennis to shop at Mick O’Dea’s grocery and pub. From the street you entered a shop stocked with everything from the humble spud to packs of washing powder and everything in between. A door then led you to a small bar with a high counter usually housing a row of creamy pints. It was the most beautiful bar in the world, not for its decor, which was very retro, but for its clientele, its history and most of all the friendly atmosphere. Micky usually had a few in there while Aggie filled the messages box with the help of the shopkeepers in their brown coats, who later delivered to the cottage.

The O’Deas are practically cousins to us, such was the closeness of the two clans. I went to school with young Mick O’Dea, who followed his passion for art and is now a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy and has served as its president for a number of years. His work is exhibited internationally and he is regarded as one of our greatest portrait painters. Some of his work adorned the walls of the pub when his older brother John ran it after their dad retired. Sadly, John also retired, and with him went much of the pub’s character and charm. Christmas week at O’Dea’s was particularly wonderful, as the townies returned from all over the world to reconnect for the festive season. A small transistor radio sat on the shelf in between various trinkets and was only switched on for news or late-night specialist roots music shows. In the adjacent room, once the family sitting room, the TV transmitted sports and The Late Late Show to a select club of locals seated in front of a constant burning fire.

The grocery business was very important to my grandfather’s generation. All the essentials were there: tea, butter, biscuits, cornflakes, cleaning supplies, all packed into large apple boxes and delivered on the day of purchase. O’Dea’s supplied many families with their weekly shop, but it was also a place of social gathering. There was a bond of trust and friendship within its community. As the years passed supermarkets forced many of these beautiful quaint shops to close, but in the case of O’Dea’s groceries, it was another harbinger of modernity, the health and safety officer, who finally closed the door for ever. A rarely used meat slicer on the counter drew her attention, and she instructed John that if he was to be selling fresh food, he’d have to add structural changes, which included a sink with hot and cold running water. John explained that he sold very little food, and was simply looking after a few of his older customers who had been coming for years; it wouldn’t be worth his while putting the extra money in for such a small return. When she insisted, John sighed and said, ‘Mam, there’s a terrible siege going on over there in Sarajevo, and I hear there’s hardly any food getting in at all. Yet I bet you the price of the sink that they sell more cold meat in downtown Sarajevo of a Saturday morning than I would here in a month of Sundays.’ Unfortunately, his pleas fell on deaf ears and within weeks the few groceries were replaced with bottles and cans of beer as the pub engulfed what was left of the grocer’s counter. Years of public service came to an abrupt end. Five generations of my family frequented O’Dea’s pub, either sipping porter, drinking orange or buying supplies, while others preferred their mugs of tea with a little chat upstairs in Mrs O’Dea’s kitchen.

AGGIE HANRAHAN

My father’s mother, Aggie, was formidable, the matriarch who ruled the house. In fairness, someone had to, as Micky was very easy-going and prone to stray onto the missing list. She ran the household with absolute authority, and cooked and baked the most delicious breads, cakes and scones. I still smell the griddle cake as she lifted it from the oven onto the table next to the butter dish and a pot of her homemade jam.

Aggie baked with sour milk purchased from a neighbour down the road. These days sour milk is not recommended and has been replaced with the conventional commercial product buttermilk. Since pasteurisation, souring your own milk is now a thing of the past. My mother usually left the bottle of milk out in the air to sour naturally before baking.

Aggie’s griddle bread

Makes one loaf

A little butter or oil, for greasing

350g plain white flour

A pinch of salt

1 tsp baking powder

1½ tbsp sugar

1 egg, beaten with 2 tbsp melted cooled butter

1½ tbsp melted butter

300ml buttermilk (you may not use it all)

Butter and homemade jam, to serve

1 Grease a griddle pan or heavy frying pan with a little butter or oil.

2 Sieve the flour, salt and baking powder into a bowl. Add the sugar. Whisk the ingredients further to add more air.

3 Add the egg, butter and most of the buttermilk. Gently bring together. If it’s too dry, add more milk, but we don’t want a very wet dough. Do not knead, as that will take the air from the mix. Shape to the size of the griddle pan, and ensure the dough is about 5cm thick.

4 Cook on a medium heat for 10 minutes.

5 Flip and cook for another 10 minutes.

6 Cut into wedges, and serve with butter and homemade raspberry jam.

Nana kept between fourteen and twenty goats in an old outhouse shed. Once a year they were herded west along the road to meet their puck, then returned to the farm and were encouraged to roam freely throughout the crag, where they feasted on nuts and roughage. They were never allowed too much time on grass, as it added far too much fat to their bodies. Kid meat was regular Easter fare in Clare, long before we turned to lamb, and the preparation of the feast varied from house to house. The meat certainly needed slow cooking, and some added juicy seasonal berries in with the roast for extra flavour, constantly basting. Others braised the meat in a broth of vegetables. The family drank the goat’s milk, and my uncle Chris says that excess goat’s milk might inadvertently find its way into the churn of cow’s milk before it was sent to the creamery. No waste was allowed, and no one said a word. Some families made yogurt, or their own version of soft cheese. One of Ireland’s best goat’s cheeses, St Tola, is made on a family farm in Inagh in County Clare run by Siobhán Ni Ghairbhith and her team, who produce a variety of stunning hard and soft cheeses.

Aggie reared her goats for the Easter celebrations, but her pride and joy were the Bronze turkeys, with each member of the family receiving one every Christmas. Some did better out of it than others, though – once she posted a turkey over to her son Tony in Birmingham, but somewhere along the line the parcel was held up and arrived two weeks after the Christmas celebrations. By all accounts the scene when it was opened was not for the faint-hearted, and left an indelible mark on the poor children present.

Aggie’s kitchen was the hub of Hanrahan life. The half door was constantly open for all to call and say hello. She always sat by the range while Micky sat at the table with his tiny transistor radio waiting for the latest result from Leopardstown. It was a great room for chat, food, music and gossip, and over the years a lot went on in that small confined space around the kitchen table with its ever-present pot of hot tea.

MOTHER

She’s an angel, my angel, she moves me, she sees the child in me

Won’t abandon me, my angel

– ‘Angel’, Someone Like You (1994)

My mother was taken from school in her very early teens and sent to work at Fawl’s on O’Connell Street in Ennis. Fawl’s was a pub, shop and tea importer also known as the Railway Bar. Large tea chests arrived from Dublin and the tea was bagged for sale. When we were babies our playpen was one of those tea chests. Dad fixed a bicycle tyre round the top for safety and all was going well for a couple of years until my brother Kieran worked out a way to topple the chest and crawl to freedom. In the evenings after the long journey home, my mother helped with household chores and tended to the needs of her four brothers. I have difficulty understanding why her parents chose that path for her, cutting short her education at such a young age, but she never discussed it much with any of us, and explained it away as being a different time. She never really spoke much at all about her childhood, but her photographs always show a smiling, beautiful young girl. She met my father when they were both young, fell in love and spent the rest of their lives falling deeper and deeper into that love.

My mother and I share a great passion for food and for many years we exchanged various tips over the phone or on my short visits home. I never left home without a plate of her luscious scrambled eggs and toast to set me on my early-morning journey back to Dublin. She was a brilliant cook and baker. After years of trying, I finally managed to record some of her baking recipes.

‘Right, Mum, are you ready to give up those recipes?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘So, Mother, your bread recipe – that brown one we all loved so much …’ I switched on the Dictaphone. She eyed it suspiciously.

‘I’m not talking into that yoke, Mike.’ I quickly found a pen and opened my copy book. I was very excited; my mother was about to give up the family’s secret recipes.

‘Well, for the brown, I get a fist or two of plain flour; a fist of the brown flour; a fist of bran; pinch of salt; a good pinch of baking soda – not too much, because that sometimes turns it a bit yellow although it never stopped ye all from eating it. I suppose it’s all really down to practice. After a while you get to know the ingredients and the feel of the mix, y’know. Oh yes – I sometimes add a little bit of sugar. Sometimes I might add raisins, or currants, although I never liked using the currants for some reason … I preferred using the larger raisins. And sometimes a pinch of ginger, or allspice. And sure, it really came down to what I had in the cupboard. That’s it.’

‘What was wrong with the currants?’

She dipped her head, grimaced and eyed me over her spectacle rims, ‘Sure I was eating most of them, Mike.’ She continued.

‘Well, then you need to mix them all with margarine or butter, half a pound or thereabouts, but I preferred the margarine, and then add an egg. Maybe not a full egg, it’s hard to know, Mike, you just have to judge it. After that I added some sour milk to bring it all together – not too wet, but it can’t be dry either.’

‘What happened if you had no sour milk?’

‘Well … if I had no sour milk, I would add a drop of vinegar to the good milk and that would sour it over about ten minutes. Did I mention not to use a full egg?’

‘Why did you bake the bread in a frying pan?’

‘Well, it was an old frying pan, and your father knocked off the handle for me as I thought it would make a good baking tray. It did – I used the same one for years and years. I’d butter the pan, put the paper at the bottom, pour the bread mix in and draw a sign of the cross on top with the knife and into the oven for about an hour or thereabouts. I’d turn the bread out then and leave it on top of the range, covered with a damp towel until we were ready to eat it. And that’s it, Mike. Very simple. And shur, ye loved it. Or at least that’s what ye told me, anyway.’

It was beautiful – not so sure about the simplicity of the recipe, though.

She went on to talk about her stews, casseroles, her mother’s cheese and that horrible homemade butter – she admonished me once again for my description of the butter. I had a beautiful afternoon with Mum, even though the baking lesson lasted minutes, but it was good to talk food with her. I could not wait to get back to my own kitchen to try out the recipes for myself and translate those fists into grams …

MY MUM’S RECIPES

After much trial and error, I managed to translate Mum’s measurements. I’m thinking a fist of flour is about 150g. So, we can take it from there.

Mum’s brown bread mix

Makes one loaf