По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

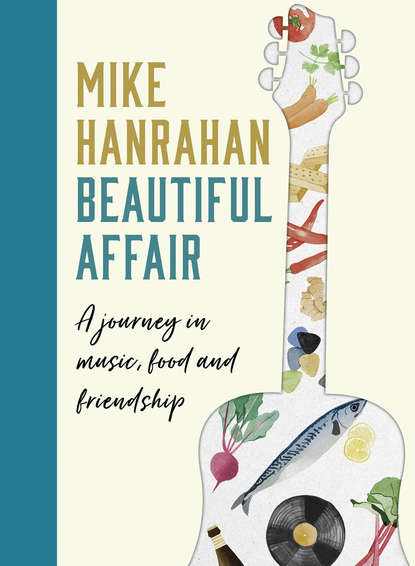

Beautiful Affair

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As a twelve-year-old I harboured ideas of a religious vocation, choosing the Order of St John of God following a visit by a brother to our school on a recruitment mission. Three of us were taken to a seminary in Celbridge, County Kildare, for a trial retreat. It was my first time being so far away from home, and I felt isolated in that seminary. Even though there were lots of people moving around, sports fields surrounded by beautiful tree-lined avenues, large dormitories, lovely food, altars and lots of prayers, I still felt alone.

On my return, my mother and I discussed the visit and she insisted that I really think about what I wanted to do. ‘Mike, I hope you’re not doing this for me or your father, because that would not be right. If you don’t want to go, then please tell me, and that will be the end of it.’ When I told her I wanted to stay at home she said, ‘Good, that’s that, then.’

We never spoke about it again until many years later when she confided she was thrilled with my decision, as she dreaded the prospect of me living away from home at such an early age. Crucially, though, she reiterated that she would have supported me either way. Mum and Dad often pointed out possible obstacles but never ever put one in our way.

As a young teen I was a true believer, and very dedicated to the Catholic Church. I spent a lot of time as an altar boy in the local Friary. It was a beautiful place and most of the Franciscans were wonderful people. We had many visiting priests and brothers who came to spend time at the centre, and when I was about fourteen, maybe fifteen, a regular visiting Franciscan brother came to our house to ask my mother for permission to take me to Galway for a weekend retreat. He sat with my mother and grandmother drinking tea, talking God and Church and praising my work at the Friary. He blessed them both and followed me out to the hallway, closing the door behind him. In the privacy of the hallway he enquired about my girlfriends, their names and which one I liked best. He began poking and feeling around my genital area, asking me if I liked it. I felt trapped, and was extremely uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to do. He continued until I managed to get to the front door. I begged him to leave me alone. As he pushed past, I noticed a lot of dandruff on the collar of his brown robe. That’s how I still remember him today. I felt ashamed, and almost dirty. I made up some excuse for turning down the trip to Galway, and I left it there in that hallway for years and years and tried not to think about it. Years later, I was walking down Abbey Street in Dublin when I spotted him coming towards me. I panicked, and hid in a doorway. As he walked by, all I noticed was the dandruff. It was still there. I wanted to scream at him, but I had no voice. I was still scared, or perhaps ashamed. I was twenty-one years of age. I never saw him again.

We all knew that certain priests in the parish were ‘dodgy’ – many altar boys relayed stories of hands slipping into their trousers. Some of us eleven- or twelve-year-olds were once brought into the office one by one by a Franciscan priest, who said he was to show us some ‘personal hygiene’ habits. He said our parents had requested it, but that we were bound to silence, as they were far too embarrassed to broach the subject further. Best keep it to ourselves. Yes, Father. Among ourselves we knew there was something wrong. We had our names for them, and we tried to steer clear of their advances and warn the younger boys, but the overriding reality was that we had a dedication to a church that controlled every aspect of our lives – and that’s where their power lay.

I have never forgotten those instances of abuse, and unfortunately to this day I still harbour a deep sense of personal responsibility for allowing them to have occurred in the first place. I have had to wrestle with that guilt every time it finds its way to the surface. I certainly felt betrayed. Thankfully, I do not own that shame any more. Healing is powerful in that regard.

In 2001 I felt compelled to write and record a song called ‘Garden of Roses’ after all the harrowing accounts of cases of child abuse by religious orders, including one particular cleric close to home. Deep down I knew I had to speak to Mum about the song’s imminent release, and if I could, talk about my own experience. Words will never truly describe that profound moment between a mother and her son. We talked and cried a little but together crossed over into a very special place of understanding. I felt such a deep sense of relief because I knew she understood my hurt, and I in turn empathised with her own very personal pain.

In the garden of roses where you came by,

Beautiful roses, the eyes of a child

In your secret desire you cut it all down.

Now the petals lay scattered on tainted ground

In the garden of roses, beautiful roses.

Hot Press founder Jackie Hayden called me after hearing the song; he wanted permission to include it in his book In Their Own Words, a compilation of personal stories from abuse victims in the Wexford region to support the Wexford Rape Crisis Centre. I was invited to perform at a few very powerful and moving healing services where the song found its true home. The song continued to make an impression with listeners as the revelations kept coming, as it was included in a 2011 book, The Rose and the Thorn by Audrey Healy and Don Mullan. In the autumn of 2018, I was invited to perform the song once again, but this time at a day of remembrance for Ireland’s lost children at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam in County Galway. It seems we have come some way from those terrible days of darkness. I certainly hope so. May the healing continue.

Now your temple has fallen, the walls cave in.

We witness the sanctum in their evil sin.

But a river once frozen deep in the mind

Flows on like a river should in the eyes of a child

In the garden of roses, those beautiful roses.

– ‘Garden of Roses’, What You Know (2002)

FAREWELL TO DAD

My dad died before the avalanche of abuse stories arrived, and I know he would have been shocked to the core. He was a very religious man, and like many of his generation lived by church rules and served without question. I have no doubt that I could have spoken openly to him about writing ‘Garden of Roses’. He would have listened and offered comfort, of that I am certain. His death in June 2000 had a profound effect on my life and my songwriting. Two years later I released the album What You Know. The title of the album is an expression he used for almost everything that he could not instantly put a name to. If he wanted you to get a paintbrush from the shed he might say, ‘Mikie, will you get the what-you-know from the shed, I want to finish that bit of painting. It’s in the box beside the what-you-know, the screwdrivers.’ You had to be on his wavelength, but we usually were.

A songwriter friend of mine once wrote of his dad’s passing, ‘The greatest man I never knew lived down the hall.’ It was such a sad song. I am glad to say I knew mine very well and we shared many great times together. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he was given nine weeks to live. Such was his strength and determination he lasted almost two years and faced it with great courage. Thankfully, I never had a slate to clean with him so we carried on as normal and tried our best to make the journey comfortable. His funeral was one of the biggest Ennis has ever seen, a testament to his wonderful personality and selfless generosity. He sits on my shoulder for every gig and I love to talk about him. He never got to see me in chef whites but I have absolutely no doubt it would have pleased him and he may have turned to Mum and said, ‘Sure, Mary, once he has a frying pan in his hand, he won’t go hungry.’

Take away the sad and lonely, all the trouble that surrounds him,

Firefighter won’t you come …

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_19434bc6-45e6-5764-987b-4ad7d3f25dec)

DOOLIN (#ulink_19434bc6-45e6-5764-987b-4ad7d3f25dec)

See all the doors swing open,

Your life’s unfolding before your very eyes,

Such a strange affair,

Walk in around, come into the sound,

Forget you’re down, feel the air, beautiful affair.

– ‘Beautiful Affair’, Light in the Western Sky (1982)

McGANN’S PUB, DOOLIN, 2018

I’m sitting on an old bench in McGann’s pub on the rugged north-west coast of County Clare. The walls of old faded photographs come to life, evoking powerful memories of a bygone era. I feel this swell of emotion, exalted and suddenly aware of the significance of these amazing colourful characters who taught me so much all those years ago. Doolin, my gateway from innocence, where the petals of youth opened wide to drink in their first rays of glorious sunshine.

Doolin sits on the edge of the Burren, that mystical landscape of limestone rock and rugged terrain where creative energy finds comfort and a true home. They say that Tolkien was inspired to write The Lord of the Rings after spending time here; Dylan Thomas married a local woman and lived in Doolin for a time; George Bernard Shaw and J. M. Synge often wrote of its beauty. In the early 1970s a new generation of free spirits arrived in Doolin from faraway places, and though some passed on through, many remained and integrated to develop a very special community. Today that community thrives and continues to provide a haven for travellers, lovers, dreamers, musicians, poets and singers. It feels so good to be back again, and it feels like I’m home.

TOMMY McGANN

In 1976 Tommy and Tony McGann returned from America and bought a run-down pub in a very quiet and neglected area of Doolin about a mile east of the action on Fisher Street, where Micho Russell held court at O’Connor’s pub, singing and playing the whistle, entertaining fans and visitors from all over Europe. The pub had been owned by two Americans who had run out of money, forcing the bank to take over, and within a couple of years the building had fallen into disrepair. Their father, Bernie McGann, sold a little plot of his land in Kilmaley to finance his sons’ venture. Neither had any previous experience in the pub trade, which resulted in much trial and even more error in the early days. Although Tommy’s management skills were almost non-existent at that time, he found a way through, with a charm that came to define him and set him apart throughout his short life.

In that same year as they took up the pub, my secondary schooling came to an end at Rice College on the banks of the river Fergus, not far away in Ennis. I was a reluctant student to say the least; I had no interest in school apart from history and economics, the latter receiving most of my academic attention. The enigmatic Jody Burns, with his appearance and antics of a nutty professor, was a gifted teacher who managed to corner my full attention on matters of supply and demand. I duly received an A in my Leaving Certificate examination in economics, which was a great shock to many – but not to Jody Burns. He was very proud of my achievement but expressed great disappointment on hearing that I would not be going on to study economics in college. These days third-level education is a natural progression for so many students, but back in the 70s the order of the day for the majority of us school-leavers was to secure a ‘grand pensionable job’, settle down, buy a house and raise a family.

Little did I know while sitting those last exams that as soon as the school books hit the waters of the river Fergus, I’d be in a car on my way up to Doolin to play music with my brother Kieran and first cousin Paul Roche, right here in this very room where I sit today in McGann’s. During that first summer of freedom I shook off the shackles of a sheltered Catholic upbringing. I made many new friends, discovered love, expression and songwriting. I recognised early on that the fish and lamprey eels of the Fergus would benefit much more from my books than I ever did, while I concentrated my further education on the life and music of North Clare and beyond.

MY FIRST KITCHEN JOB

Up to the mid-40s transatlantic flights – mainly seaplanes – had to stop to refuel at Foynes in West Limerick on their way to continental Europe. During the Second World War Foynes became the busiest airport in the world. Shannon Airport was then established in 1945 as Ireland’s first international airport, and within a few years it became the world’s first duty-free airport, operating as a gateway between North America and Europe, as most aircraft still required refuelling for long-haul flights.

In that summer of ’76 I got a job as a kitchen porter in the airport’s ‘free-flow’ restaurant, doing my best to get to Doolin for our Tuesday and Thursday night sessions and up again on Friday evening for a weekend of music and craic. The job was supposed to be a stepping stone either to a culinary career or to a more secure position in the airport or surrounding industrial hub. The busy kitchen served passengers, flights, all airport staff and stocked all duty-free restaurants. Most of my day was spent either on wash-up or working the conveyor belt, which delivered mounds of dirty dishes and cutlery to the sinks. Life as a kitchen porter was non-stop grief, thanks in particular to an ogre of a chef who barked and bellowed orders through an early-morning fug of stale alcohol. Stockpots and skillet missiles whizzed past my right ear to rattle against the sides of the stainless-steel basin before sinking into an angry, greasy ocean of bobbing and weaving pots and pans. The two of us manning the station were not allowed to speak a word, but we soon developed early warning signals for any incoming, including the main man himself, who would storm over with a badly washed pot, reload and fire it back at us again with bonus expletives. By the end of lunch, his anger grew as his hangover craved its afternoon cure. His venomous eyes have stayed with me, but it was a lesson to me to learn my surroundings inside out.

My next-door neighbour and childhood friend Ken Shaughnessy also worked in that kitchen as a commis chef. He went on to culinary college and became an executive head chef for an international hotel chain in Germany. On the very rare occasions we meet, we toast many schnapps to our wonderful childhood, that kitchen and good old Cerberus. Perhaps he was the making of us after all, as our love of food survived and neither of us have ever tolerated kitchen bullies, no matter how important they consider themselves. I will never understand how aggressive chefs get away with humiliating people in their place of work.

I moved quickly from the kitchen to the duty-free mail-order department, packing and posting Waterford crystal, Belleek china, shillelaghs and leprechauns to exotic-sounding destinations like Pine Ridge, Vermont, Wyoming, Montana and Biloxi. I finally left Shannon to work with my friend TV Honan at a newly opened drop-in centre for teenagers in the old refurbished National School in Ennis. It was the first of its kind in Ireland, the brainchild of Sean Sexton, a very proactive, clued-in priest. We called it the Green Door after a short story by American writer O. Henry, a tale of romance, adventure and fate as we search for a door to opportunity. I often think that the story somehow reflected my decision to break free from that grand pensionable position to search for my own green door. With an unyielding determination to find a way to the music I convinced Mum and Dad by telling them my wages at the Green Door were higher than at Shannon, when in fact they were a lot lower, but I figured I could make up the loss from sessions and gigs.

ROOM WITH SEA VIEW

On my weekend visits to Doolin I slept behind the pub in a caravan and in tents beside the beautiful Aille River, or found a sleeping space in the upstairs restaurant. Come the morning there was the usual scurry to clear the beds and clean up last night’s fun to get ready for early lunch. One summer a group of German tourists found their way into a disused, dilapidated, roofless house at the entrance to Doolin pier, cleared it out, filled it with straw and hay and pinned a sign at the front entrance:

Doolin Hilton Hotel

All welcome

Please keep tidy

After closing time, we had some memorable nights at that waterfront Hilton. Everyone checked in, signed the guest book, played music, sang songs and listened to stories from all around the world. We heard about Aboriginal dream time, the Northern Lights, American Indians, Nordic folk tales and magical Dutch fairy stories, while smoking reefers and drinking beers on beds of straw beneath a blanket of sparkling stars. All strangers who entered left as friends. I fell in love there with Bebke Smits, a free-spirited young woman from Boxtel in the Brabant district of southern Holland. Bebke sang Dutch folk songs, wrote and recited deep and weird poetry, danced very freely and was extremely comfortable in her hippie skin. She introduced me to vegetarian food, and gave me my first Herman Hesse novel, Narcissus and Goldmund, a book I return to time and again. It’s a poignant tale about young Goldmund, who develops a friendship with a slightly older and more committed monk, Narcissus, at a monastery somewhere in Germany. Goldmund strays into the woods one night, where he meets a beautiful young woman who seduces him. The confused novice seeks counsel from the older Narcissus, who encourages him to leave the monastery and embrace life beyond the walls rather than remain in search of salvation. On the journey that follows, Goldmund becomes a talented carver but refuses to join the carving guild, preferring to continue unbound on his road to understanding. He meets and loves many other women along the way, and survives the Black Death and all its ugliness. Eventually he returns to his friend Narcissus, where in the monastery the artist and philosopher speak freely about their lives in a beautifully written story.