По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

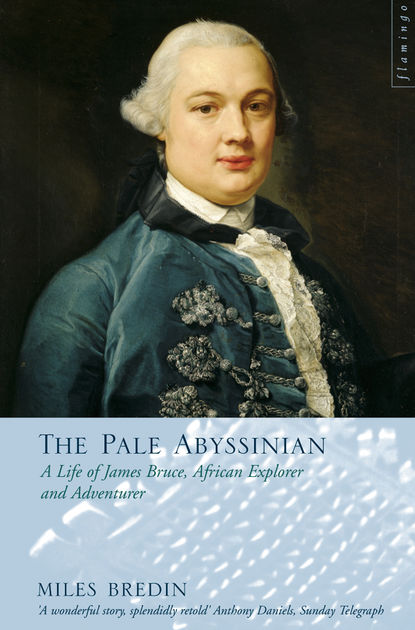

The Pale Abyssinian: The Life of James Bruce, African Explorer and Adventurer

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Pale Abyssinian: The Life of James Bruce, African Explorer and Adventurer

Miles Bredin

The biography of one of Britain’s greatest explorers by a brilliant young writer.The achievements of James Bruce are the stuff of legends. In a time when Africa was an unexplored blank on the map, he discovered the source of the Blue Nile, lived with the Emperor of Abyssinia at court in Gondar, commanded the Emperor’s horse guard in battle and fell in love with a princess.After twelve years of travels, and having cheated death on countless occasions, Bruce returned to England from his Herculean adventures only to be ridiculed and despised as a fake by Samuel Johnson and the rest of literary London. It was only when explorers penetrated the African Interior one hundred years later and were asked if they were friends with a man called Bruce, that it was finally confirmed that Bruce really had achieved what he had claimed.The Pale Abyssinian is the brilliantly told story of a man’s battle against almost insurmountable odds in a world nobody in Europe knew existed. Born in 1730, the son of a Scottish laird, James Bruce was an enormous man of six foot four with dark red hair, and he had to use all of his bearing and his wits to survive the ferocious physical battles and vicious intrigues at court in Abyssinia (Ethiopia today). His biographer, Miles Bredin, through ingenious detective work both in Bruce’s journals and in Ethiopia itself, has also unearthed a darker mission behind his travels: a secret quest to find the lost Ark of the Covenant.A highly talented and daring young writer, Miles Bredin has created a stunning account of the life and adventures of an extraordinary man. The Pale Abyssinian will re-establish once and for all the name of one of Britain’s greatest explorers who penetrated the African Interior over a century before the likes of Stanley, Livingstone and Burton set foot on the continent.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

THE PALE ABYSSINIAN

A LIFE OF JAMES BRUCE,

AFRICAN EXPLORER AND ADVENTURER

Miles Bredin

DEDICATION (#ulink_c4c7f13e-9d38-57bb-ac7e-f712eacfa4fd)

For my father, James Bredin

In memory of James Bredin, Carlos Mavroleon

and Giles Thornton

CONTENTS

Cover (#u8845d184-6828-56c0-ac64-41a678c1686c)

Title Page (#uefc2dc4b-1898-53da-a42e-01198b7310e1)

Dedication (#ub5765d14-4894-5385-a71d-36f60307f263)

Map (#ulink_17aa8455-8da1-5ada-aa1f-b33e6addf710)

Introduction (#uf0d6d130-c7e6-5462-9314-9d6a7319ad5c)

1 The Jacobite Hanoverian (#ud0d1b45d-e2ca-5f49-835d-34833890e044)

2 The Calamitous Consul (#u002cb0f6-af27-5200-94bb-3b7e6c4b68ec)

3 The Enlightened Tourist (#u94022ca0-73d1-5c50-a47d-81d66bfac55d)

4 Into the Unknown (#litres_trial_promo)

5 All Points Quest (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Courting Disaster (#litres_trial_promo)

7 The Coy Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

8 The Siren Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

9 The Highland Warrior (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Astronomical Success (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Flight to Egypt (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Rover’s Return (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Great Scot (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

MAP (#ulink_c748964f-5838-573b-bfe7-1fad44f891e6)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_d824edfa-c2bb-56ae-8d04-20e1f357ed24)

James Bruce was one of the world’s greatest explorers. A full century before the age of Stanley and Livingstone, he ventured deep into the African hinterland and added vast tracts of country to the map of the known world. His greatest achievements were in Abyssinia where he discovered the source of the Nile, a riddle that had preoccupied the world since the ancient Egyptians began to wonder where all the water came from. In his success, however, lay his failure. It was the wrong Nile – the Blue rather than the White – and he was so far in advance of any other African explorers that no one believed him anyway. It was another hundred years before Speke and Burton made their discovery of Lake Victoria and finally solved the ‘opprobrium of geographers’ that had for so long obsessed the world. Bruce was of course not the first to discover the source of the Nile; the Ethiopians were, from ancient times, well aware that the source lay in their country.

Bruce has an undeserved and unenviable reputation. He is generally remembered, if at all, as ill-tempered and a liar. And whilst there is a certain amount of truth in both accusations, they also leave a great deal unsaid. He was foul-tempered but only towards the end of his life when, his reputation in tatters, he was suffering from myriad illnesses; and he was a liar, but only in a small way, as were all the explorers who followed him. The main accusation against him – that he never went to Abyssinia – was proved to be a fallacy fifty years after he died, by which time it was too late to restore his reputation. In this book I hope to do that and more. Bruce was a colossus of his age. He inspired Mungo Park to trace the Niger, Samuel Taylor Coleridge to write ‘Kubla Khan’ and generations of scholars to learn about the ancient culture of Ethiopia. He should be remembered for that and not for the envy he inspired in others.

Bruce could not have achieved half that he did had he been the vicious old curmudgeon described in popular folklore. In fact, in his heyday he was considered charming and handsome as well as extraordinarily large: he was six foot four and immensely strong. Women everywhere adored him, from the harems of North Africa to the salons of Paris and the court of the Abyssinian Emperor. Men too loved him, but only a certain kind of man; in them he inspired an almost fanatical loyalty. He could ride like an Arab, shoot partridge from the saddle at the gallop and faced danger with icy calm. These particular manly virtues were all very well in the East where they won him friends and influence but in the eighteenth-century world of Horace Walpole, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell they were of little use. His bluff, no-nonsense attitude won him few friends at the court of George III and his rage at having his word doubted only made him seem the more ridiculous.

It is through the eyes of those three men – Walpole, Johnson and Boswell – that most is known about Bruce, and it is their opinions and viewpoints that I hope to redress. Bruce lived for sixty-four years; the first thirty and last twenty were spent in Britain. He was in his prime during the fourteen or so years in between, exploring the unknown world with a sword in his hand and a pistol at his side, leaving weeping women and vanquished enemies in his wake. The painter Johann Zoffany met him soon after his return to the West. He saw Bruce as he should be seen: ‘This great man; the wonder of his age, the terror of married men, and a constant lover.’ This is the Bruce about whom I have written: brilliant intellectual, talented diplomat and fearless explorer but, above all, a magnificent man.

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_78cdbd68-2a3e-52b1-a3ec-ed951fcf2334)

THE JACOBITE HANOVERIAN (#ulink_78cdbd68-2a3e-52b1-a3ec-ed951fcf2334)

On a damp evening in April 1794 James Bruce sat gazing from the window of his Stirlingshire dining-room and saw a woman walking unaccompanied to her carriage. Having levered his considerable bulk from a chair, he rushed to her aid to perform what would be his final chivalrous deed. On the sixth step of the staircase, he slipped, fell on his head and was dead by morning. It was an ignominious end to a life of rare adventure.

During the previous sixty-four years, Bruce had crossed the Nubian Desert, climbed the bandit-bedevilled mountains of Abyssinia, been shipwrecked off the North African coast and sentenced to death in Sudan. He had lived with the rulers of undiscovered kingdoms and slept with their daughters, been granted titles and lands by barbarian warlords and had then returned – more or less intact – to the place of his birth, a small town near the Firth of Forth where very few believed he had done what he claimed and many pilloried him as a liar and a fraud. Decades after his death, it began to emerge that most of the time he had been telling the truth. He had travelled in Abyssinia and the Sudan, he had been to the source of the Blue Nile and he had charted the Red Sea. But by then he had lapsed into obscurity and his successors had outdone him in both fame and infamy.

Bruce had great charm but he could also be utterly brutal and cantankerous. He was generous to strangers but they crossed him at their peril. He could tumble down African mountainsides and cheat death at the hands of jihad-inspired potentates, yet in the end his demise was caused by a trivial accident. In the early nineteenth century a few commentators wrote about his life by glossing over its inconsistencies and showering him with praise. His own, five-volume Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772 & 1773 is packed with invaluable information but should have been published as at least three different books. It has not been published in full for decades.

In spite of his prolixity, it is the things that Bruce left out of his life’s work that make him so fascinating. There are many detectable errors in the book (carelessly, he failed to consult his notes) but there are also eloquent omissions and deliberate evasions which contributed to his not being believed on his return. He failed to address the rumour that he had killed the artist who accompanied him and indeed scarcely refers to him in the book. He makes almost no mention of the Ark of the Covenant when one of the few things then known about Abyssinia was that it was claimed to be guarding the Ark. It was, though, his manner which did the greatest damage to his credibility.

Haughty and proud (the portmanteau word ‘paughty’ might almost have been coined for him), he once forced a visitor to eat raw meat after the unfortunate man had expressed doubt at its being the Abyssinians’ favourite dish. Bruce brooked no criticism and eventually refused to discuss his work with anyone except an adoring audience. He was prickly even to his disciples. Too great a display of amazement at his astonishing stories was often interpreted as disbelief and no one was allowed to accuse Bruce of lying and walk away. An expert swordsman from a long line of pugnacious ancestors, he gained notoriety after challenging his former fiancée’s husband to a duel. It was understood that the same treatment would be handed out to what he called his ‘chicken-hearted critics’.

He was born in 1730, with the blood of the Hays and the Bruces, both families famous for their martial history, coursing through his veins. In a century of almost continuous warfare, however, 1730 was a surprisingly peaceful time to arrive. The Treaty of Seville between France, Spain and England had been signed the year before and had produced a temporary lull in the Catholic – Protestant wars that dominated the period. James’s father, David Bruce of Kinnaird, was a Hay of Woodcockdale (a scion of the better known Hays of Errol), a family that fought with honour at Bannockburn and still one of the oldest in Scotland. David’s father had been forced by contract to adopt his wife’s name – Bruce – which can be traced in a moderately straight line to Robert the Bruce, in order to inherit the estate of Kinnaird. The two great Scottish families had been inextricably linked since before Bannockburn and the marriage was merely another link between them.

For a young Scot with such a surname, born so soon after the Act of Union of 1707, it would seem inevitable that James should support the Jacobites, but this was not the case. His father, David, had endured an extremely close brush with death in the aftermath of the 1715 uprising with which he had been intimately involved. He had been sentenced to death and had only escaped the gallows because of the reluctance of Scottish judges to execute Scots accused of breaking English laws. This had been a chastening experience and he was adamant that his son should not follow in his rebellious footsteps. Having died of a ‘lingering illness’, probably tuberculosis, before James’s fourth birthday, his mother Marion had no influence on his upbringing. Whilst Bonnie Prince Charlie was being brought up in exile, so too was James, the former in Catholic France, the latter in staunchly Protestant England. The Young Pretender and his army actually marched past Kinnaird on the way to the final showdown at Culloden but the young James was not there to witness it, nor the Battle of Falkirk which was fought a few miles away. Instead he was in London being raised as an English gentleman. He was forever to remain one.

Well before the ’45 uprising, David Bruce was showing a vulnerability to the charms of women that his son was to inherit. Having fathered James with Marion Graham, he went on to father six more sons and two daughters with his second wife, Agnes Glen. Preoccupied by this frenzied period of procreation and fearful that his son would be caught up in the Jacobite machinations of their Stirlingshire neighbours, the laird of Kinnaird contrived to send his son as far away from their influence as possible. At the age of eight, James was sent to London where for the next few years he lived with the family of his uncle, William Hamilton. From 1738 he was taught both by Counsellor Hamilton and by a Mr Graham who had a small private school in London, but by 1742 it was decided that he needed more formal education. He was sent to Harrow, where he excelled.

Miles Bredin

The biography of one of Britain’s greatest explorers by a brilliant young writer.The achievements of James Bruce are the stuff of legends. In a time when Africa was an unexplored blank on the map, he discovered the source of the Blue Nile, lived with the Emperor of Abyssinia at court in Gondar, commanded the Emperor’s horse guard in battle and fell in love with a princess.After twelve years of travels, and having cheated death on countless occasions, Bruce returned to England from his Herculean adventures only to be ridiculed and despised as a fake by Samuel Johnson and the rest of literary London. It was only when explorers penetrated the African Interior one hundred years later and were asked if they were friends with a man called Bruce, that it was finally confirmed that Bruce really had achieved what he had claimed.The Pale Abyssinian is the brilliantly told story of a man’s battle against almost insurmountable odds in a world nobody in Europe knew existed. Born in 1730, the son of a Scottish laird, James Bruce was an enormous man of six foot four with dark red hair, and he had to use all of his bearing and his wits to survive the ferocious physical battles and vicious intrigues at court in Abyssinia (Ethiopia today). His biographer, Miles Bredin, through ingenious detective work both in Bruce’s journals and in Ethiopia itself, has also unearthed a darker mission behind his travels: a secret quest to find the lost Ark of the Covenant.A highly talented and daring young writer, Miles Bredin has created a stunning account of the life and adventures of an extraordinary man. The Pale Abyssinian will re-establish once and for all the name of one of Britain’s greatest explorers who penetrated the African Interior over a century before the likes of Stanley, Livingstone and Burton set foot on the continent.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

THE PALE ABYSSINIAN

A LIFE OF JAMES BRUCE,

AFRICAN EXPLORER AND ADVENTURER

Miles Bredin

DEDICATION (#ulink_c4c7f13e-9d38-57bb-ac7e-f712eacfa4fd)

For my father, James Bredin

In memory of James Bredin, Carlos Mavroleon

and Giles Thornton

CONTENTS

Cover (#u8845d184-6828-56c0-ac64-41a678c1686c)

Title Page (#uefc2dc4b-1898-53da-a42e-01198b7310e1)

Dedication (#ub5765d14-4894-5385-a71d-36f60307f263)

Map (#ulink_17aa8455-8da1-5ada-aa1f-b33e6addf710)

Introduction (#uf0d6d130-c7e6-5462-9314-9d6a7319ad5c)

1 The Jacobite Hanoverian (#ud0d1b45d-e2ca-5f49-835d-34833890e044)

2 The Calamitous Consul (#u002cb0f6-af27-5200-94bb-3b7e6c4b68ec)

3 The Enlightened Tourist (#u94022ca0-73d1-5c50-a47d-81d66bfac55d)

4 Into the Unknown (#litres_trial_promo)

5 All Points Quest (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Courting Disaster (#litres_trial_promo)

7 The Coy Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

8 The Siren Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

9 The Highland Warrior (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Astronomical Success (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Flight to Egypt (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Rover’s Return (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Great Scot (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

MAP (#ulink_c748964f-5838-573b-bfe7-1fad44f891e6)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_d824edfa-c2bb-56ae-8d04-20e1f357ed24)

James Bruce was one of the world’s greatest explorers. A full century before the age of Stanley and Livingstone, he ventured deep into the African hinterland and added vast tracts of country to the map of the known world. His greatest achievements were in Abyssinia where he discovered the source of the Nile, a riddle that had preoccupied the world since the ancient Egyptians began to wonder where all the water came from. In his success, however, lay his failure. It was the wrong Nile – the Blue rather than the White – and he was so far in advance of any other African explorers that no one believed him anyway. It was another hundred years before Speke and Burton made their discovery of Lake Victoria and finally solved the ‘opprobrium of geographers’ that had for so long obsessed the world. Bruce was of course not the first to discover the source of the Nile; the Ethiopians were, from ancient times, well aware that the source lay in their country.

Bruce has an undeserved and unenviable reputation. He is generally remembered, if at all, as ill-tempered and a liar. And whilst there is a certain amount of truth in both accusations, they also leave a great deal unsaid. He was foul-tempered but only towards the end of his life when, his reputation in tatters, he was suffering from myriad illnesses; and he was a liar, but only in a small way, as were all the explorers who followed him. The main accusation against him – that he never went to Abyssinia – was proved to be a fallacy fifty years after he died, by which time it was too late to restore his reputation. In this book I hope to do that and more. Bruce was a colossus of his age. He inspired Mungo Park to trace the Niger, Samuel Taylor Coleridge to write ‘Kubla Khan’ and generations of scholars to learn about the ancient culture of Ethiopia. He should be remembered for that and not for the envy he inspired in others.

Bruce could not have achieved half that he did had he been the vicious old curmudgeon described in popular folklore. In fact, in his heyday he was considered charming and handsome as well as extraordinarily large: he was six foot four and immensely strong. Women everywhere adored him, from the harems of North Africa to the salons of Paris and the court of the Abyssinian Emperor. Men too loved him, but only a certain kind of man; in them he inspired an almost fanatical loyalty. He could ride like an Arab, shoot partridge from the saddle at the gallop and faced danger with icy calm. These particular manly virtues were all very well in the East where they won him friends and influence but in the eighteenth-century world of Horace Walpole, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell they were of little use. His bluff, no-nonsense attitude won him few friends at the court of George III and his rage at having his word doubted only made him seem the more ridiculous.

It is through the eyes of those three men – Walpole, Johnson and Boswell – that most is known about Bruce, and it is their opinions and viewpoints that I hope to redress. Bruce lived for sixty-four years; the first thirty and last twenty were spent in Britain. He was in his prime during the fourteen or so years in between, exploring the unknown world with a sword in his hand and a pistol at his side, leaving weeping women and vanquished enemies in his wake. The painter Johann Zoffany met him soon after his return to the West. He saw Bruce as he should be seen: ‘This great man; the wonder of his age, the terror of married men, and a constant lover.’ This is the Bruce about whom I have written: brilliant intellectual, talented diplomat and fearless explorer but, above all, a magnificent man.

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_78cdbd68-2a3e-52b1-a3ec-ed951fcf2334)

THE JACOBITE HANOVERIAN (#ulink_78cdbd68-2a3e-52b1-a3ec-ed951fcf2334)

On a damp evening in April 1794 James Bruce sat gazing from the window of his Stirlingshire dining-room and saw a woman walking unaccompanied to her carriage. Having levered his considerable bulk from a chair, he rushed to her aid to perform what would be his final chivalrous deed. On the sixth step of the staircase, he slipped, fell on his head and was dead by morning. It was an ignominious end to a life of rare adventure.

During the previous sixty-four years, Bruce had crossed the Nubian Desert, climbed the bandit-bedevilled mountains of Abyssinia, been shipwrecked off the North African coast and sentenced to death in Sudan. He had lived with the rulers of undiscovered kingdoms and slept with their daughters, been granted titles and lands by barbarian warlords and had then returned – more or less intact – to the place of his birth, a small town near the Firth of Forth where very few believed he had done what he claimed and many pilloried him as a liar and a fraud. Decades after his death, it began to emerge that most of the time he had been telling the truth. He had travelled in Abyssinia and the Sudan, he had been to the source of the Blue Nile and he had charted the Red Sea. But by then he had lapsed into obscurity and his successors had outdone him in both fame and infamy.

Bruce had great charm but he could also be utterly brutal and cantankerous. He was generous to strangers but they crossed him at their peril. He could tumble down African mountainsides and cheat death at the hands of jihad-inspired potentates, yet in the end his demise was caused by a trivial accident. In the early nineteenth century a few commentators wrote about his life by glossing over its inconsistencies and showering him with praise. His own, five-volume Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772 & 1773 is packed with invaluable information but should have been published as at least three different books. It has not been published in full for decades.

In spite of his prolixity, it is the things that Bruce left out of his life’s work that make him so fascinating. There are many detectable errors in the book (carelessly, he failed to consult his notes) but there are also eloquent omissions and deliberate evasions which contributed to his not being believed on his return. He failed to address the rumour that he had killed the artist who accompanied him and indeed scarcely refers to him in the book. He makes almost no mention of the Ark of the Covenant when one of the few things then known about Abyssinia was that it was claimed to be guarding the Ark. It was, though, his manner which did the greatest damage to his credibility.

Haughty and proud (the portmanteau word ‘paughty’ might almost have been coined for him), he once forced a visitor to eat raw meat after the unfortunate man had expressed doubt at its being the Abyssinians’ favourite dish. Bruce brooked no criticism and eventually refused to discuss his work with anyone except an adoring audience. He was prickly even to his disciples. Too great a display of amazement at his astonishing stories was often interpreted as disbelief and no one was allowed to accuse Bruce of lying and walk away. An expert swordsman from a long line of pugnacious ancestors, he gained notoriety after challenging his former fiancée’s husband to a duel. It was understood that the same treatment would be handed out to what he called his ‘chicken-hearted critics’.

He was born in 1730, with the blood of the Hays and the Bruces, both families famous for their martial history, coursing through his veins. In a century of almost continuous warfare, however, 1730 was a surprisingly peaceful time to arrive. The Treaty of Seville between France, Spain and England had been signed the year before and had produced a temporary lull in the Catholic – Protestant wars that dominated the period. James’s father, David Bruce of Kinnaird, was a Hay of Woodcockdale (a scion of the better known Hays of Errol), a family that fought with honour at Bannockburn and still one of the oldest in Scotland. David’s father had been forced by contract to adopt his wife’s name – Bruce – which can be traced in a moderately straight line to Robert the Bruce, in order to inherit the estate of Kinnaird. The two great Scottish families had been inextricably linked since before Bannockburn and the marriage was merely another link between them.

For a young Scot with such a surname, born so soon after the Act of Union of 1707, it would seem inevitable that James should support the Jacobites, but this was not the case. His father, David, had endured an extremely close brush with death in the aftermath of the 1715 uprising with which he had been intimately involved. He had been sentenced to death and had only escaped the gallows because of the reluctance of Scottish judges to execute Scots accused of breaking English laws. This had been a chastening experience and he was adamant that his son should not follow in his rebellious footsteps. Having died of a ‘lingering illness’, probably tuberculosis, before James’s fourth birthday, his mother Marion had no influence on his upbringing. Whilst Bonnie Prince Charlie was being brought up in exile, so too was James, the former in Catholic France, the latter in staunchly Protestant England. The Young Pretender and his army actually marched past Kinnaird on the way to the final showdown at Culloden but the young James was not there to witness it, nor the Battle of Falkirk which was fought a few miles away. Instead he was in London being raised as an English gentleman. He was forever to remain one.

Well before the ’45 uprising, David Bruce was showing a vulnerability to the charms of women that his son was to inherit. Having fathered James with Marion Graham, he went on to father six more sons and two daughters with his second wife, Agnes Glen. Preoccupied by this frenzied period of procreation and fearful that his son would be caught up in the Jacobite machinations of their Stirlingshire neighbours, the laird of Kinnaird contrived to send his son as far away from their influence as possible. At the age of eight, James was sent to London where for the next few years he lived with the family of his uncle, William Hamilton. From 1738 he was taught both by Counsellor Hamilton and by a Mr Graham who had a small private school in London, but by 1742 it was decided that he needed more formal education. He was sent to Harrow, where he excelled.