По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

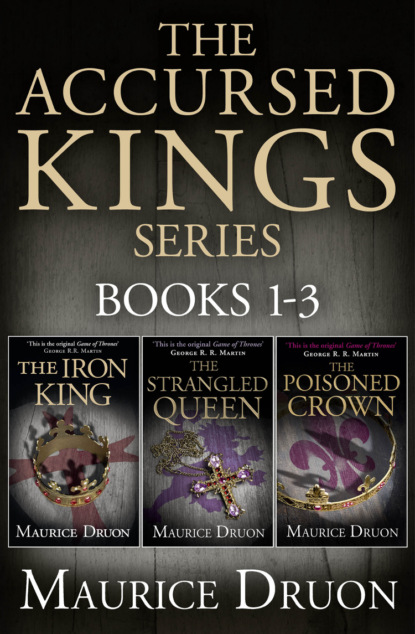

The Accursed Kings Series Books 1-3: The Iron King, The Strangled Queen, The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Gautier,’ he murmured, ‘I’m happy tonight. Are you?’

‘I’m well content, Philippe.’

Thus spoke the two brothers Aunay, Gautier and Philippe, as they went to the meeting Blanche and Marguerite had arranged as soon as they knew their husbands would be detained by the King. And it was the Countess of Poitiers who, once more a go-between, had delivered the message.

Philippe d’Aunay found it difficult to keep his happiness and impatience under control. His distress of the morning had disappeared, all his suspicions seemed unjust and vain. Marguerite had sent for him; for him Marguerite was running every risk; in a few moments he would be holding her in his arms and he swore that he would be the most tender, gay and ardent lover in the world.

The boat grounded on the bank over which rose the high wall of the tower. The last spate had left a shoal of mud.

The ferryman lent his arm to assist the two young men ashore.

‘You understand what you’ve got to do, fellow?’ said Gautier. ‘You’ll wait for us close by and don’t be seen.’

‘I’ll wait for the rest of my life, young sir, if you’ll pay me for it,’ said the ferryman.

‘Half the night will be enough,’ said Gautier.

He gave him a silver groat, twelve times what the journey was worth, and promised him another upon their return. The ferryman bowed low.

Taking care not to slip or get too muddy, the two brothers crossed the short distance to a postern and knocked a prearranged signal. The door was silently opened.

‘Good evening, Sirs,’ said the maid whom Marguerite had brought from Burgundy.

She carried a lantern and, having barricaded the door behind them, led the way into a turret staircase.

She showed them into the big room of the tower on the first floor. Its only light was a huge fire of logs on an open hearth. The glow rose and was lost among the tops of the twelve arches supporting the barrel roof.

Like Marguerite’s, this room too was scented with jasmin; the furnishings seemed impregnated with it, the gold-embroidered hangings on the walls, the carpets, the furs of wild beasts spread about on low beds in the oriental manner.

The princesses were not there. The maid went out, saying that she would inform them of their arrival.

The two young men, having taken off their cloaks, went over to the fire and automatically held out their hands to the warmth.

Gautier d’Aunay was two years older than his brother, whom he very much resembled, though he was shorter, more solidly built and fairer. He had a thick neck, pink cheeks and laughed at life. He was not, as was his brother, a prey to passion. He was married – and well married – to a Montmorency by whom he already had three children.

‘I always wonder,’ he said, as he warmed his hands, ‘why Blanche took me for a lover and, indeed, why she has a lover at all. As for Marguerite, it’s obvious. One’s only got to look at Louis of Navarre, with his downcast eyes, his gawky walk and hollow chest, and then compare him with you, to understand. And then, of course, there are other reasons of which we know.’

He was alluding to certain secrets of the alcove, to the King of Navarre’s lack of sexual vigour and to the disharmony existing between husband and wife.

‘But I don’t understand Blanche,’ Gautier d’Aunay went on. ‘She’s got a good-looking husband, much better-looking than I am. Of course he is, Philippe, don’t protest. He looks exactly like his father the King. He loves her and, I believe, whatever she may say, that she loves him. Then why does she do it? Every time I see her I wonder why such a piece of luck should have come my way.’

‘Because she wants to do the same as her cousin,’ Philippe replied.

There were light steps and whisperings in the passage that led from the tower to the house, and the two princesses came in.

Philippe moved quickly towards Marguerite but suddenly stopped short. He had caught sight, at his mistress’s belt, of the gold purse with the precious stones that had so much angered him in the morning.

‘What’s the matter with you, Philippe darling?’ Marguerite asked, her arms extended towards him, her face raised to receive a kiss. ‘Aren’t you happy this evening?’

‘Perfectly,’ he answered coldly.

‘What’s happened? What are you angry about now?’

‘Have you put that on merely to annoy me?’ asked Philippe, pointing to the purse.

She laughed loudly and happily.

‘How silly you are, how jealous and how sweet! Didn’t you realise that I was teasing you? Just to calm you down, I’ll give you the purse. You’ll know then that it was no present from a lover.’

She took the purse from her waist and attached it to Philippe’s belt. He was bewildered and made a gesture of protest.

‘Yes, yes, I want you to have it,’ she said. ‘Now it really is a love-gauge for you. No, don’t refuse. Nothing is too fine for my beautiful Philippe. But don’t ask me again where the purse came from, or I shall have to take it back. I can only swear to you that it was not given me by a man. Besides, Blanche has got one too. Blanche,’ she said, turning to her cousin, ‘show your purse to Philippe. I have given him mine.’

Blanche was lying on one of the beds in the darkest part of the room. Gautier was beside her, kneeling on one knee and covering her throat and hands with kisses.

‘I’ll wager,’ Marguerite murmured in Philippe’s ear, ‘that within a minute your brother will have received a similar present.’

Blanche raised herself on an elbow and said, ‘Isn’t it very rash, Marguerite, and have we the right to do it?’

‘Of course,’ Marguerite answered. ‘No one but Jeanne has seen them or even knows that we have received them.’

‘All right,’ cried Blanche; ‘I don’t want my beautiful lover to be less loved and less adorned than yours.’

And she took off her purse which Gautier accepted with an easy grace since his brother had already done so.

Marguerite gave Philippe a look which said, ‘Didn’t I tell you so?’

Philippe smiled at her. ‘How astonishing Marguerite is,’ he thought.

He could never make her out or understand her. Was she the same woman who that morning had been cruel, teasing, perfidious, who had played with him as she might have turned a pheasant on a spit, and who now, having given him a present worth a hundred and fifty pounds, lay in his arms, submissive, tender, almost quivering?

‘I believe the reason I love you so much,’ he murmured, ‘is because I don’t understand you.’

No compliment could have given Marguerite greater pleasure. She thanked Philippe by burying her lips in his neck. Suddenly she disengaged herself and stood listening. Then she cried, ‘Do you hear them? The Templars. They’re being led out to the stake.’

Bright-eyed, her face alive with a sinister curiosity, she dragged Philippe to the window, a high funnel-shaped loophole built in the thickness of the wall, and opened the casement.

The loud murmuring of the crowd flowed into the room.

‘Blanche, Gautier, come and look!’ said Marguerite.

But Blanche replied in a happy, quavering voice, ‘Oh! no, I’m much too happy where I am.’

Between the two princesses and their lovers all shame had long since vanished. It was their custom to enjoy all the pleasures of love in each other’s presence. If Blanche on occasion turned her eyes away, and hid her nakedness in the shadowy corners of the room, Marguerite derived an added pleasure from watching others making love, as she did from being watched herself.

But at the moment, glued to the window, she was spellbound by the spectacle of what was taking place in the middle of the Seine. There, on the Island of the Jews, a hundred archers, drawn up in a circle, held lighted torches in their hands; and the flames of the torches, flaring in the wind, formed a central pool of light in which could clearly be seen the huge pile of faggots and the assistant-executioners clambering over it and stacking heaps of logs. On the near side of the archers, the island, which normally was nothing but a field where cows and goats grazed, was covered with people; while a fleet of boats upon the river carried others who wished to watch the execution.

Coming from the right bank, a larger boat than the rest, carrying standing men-at-arms, had just come alongside the island. Two tall grey figures disembarked from it. They wore curious hats and were preceded by a monk bearing a cross. The murmuring of the crowd became a clamour. Almost at the same instant lights went on in the great loggia in the water-tower which stood on the point of the palace garden. Shadows emerged from the darkness of the loggia, and suddenly the clamouring of the crowd ceased. The King and his Council had taken their places.