По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

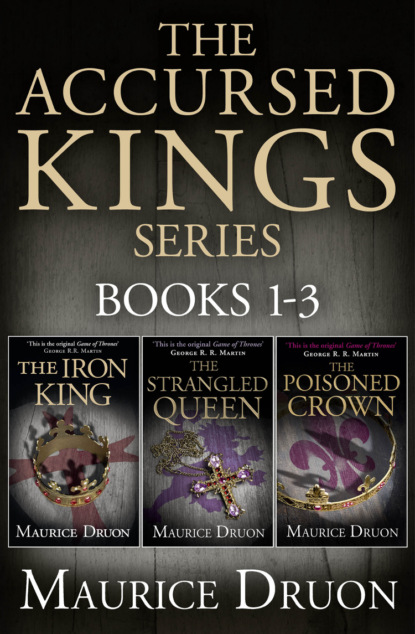

The Accursed Kings Series Books 1-3: The Iron King, The Strangled Queen, The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Arm in arm to avoid slipping, they made their way by the wall of the Hôtel-de-Nesle. As they went, they continued to search the darkness. There was no sign of the ferryman.

‘I wonder who can have given them to them,’ Philippe said suddenly.

‘What are you talking about?’

‘The purses.’

‘Oh, you’re still thinking of that, are you?’ said Gautier. ‘For my part, I must admit I don’t care a damn. Of all the presents they’ve made us, we’ve never had finer ones than these.’

As he talked he stroked the purse at his belt, feeling the precious stones in relief beneath his fingers.

‘It can’t be anyone connected with the Court,’ Philippe went on. ‘Marguerite and Blanche would never have risked their being recognised on us. So, who can it be? A present from their family in Burgundy perhaps? It’s so odd that they didn’t want to tell us.’

‘Which do you prefer,’ asked Gautier, ‘to know or to have?’

Philippe was about to reply when they heard a low whistle in front of them. They started, and at once put their hands to their daggers. They had no other weapons with them, having decided to leave their swords behind as they would be in the way.

An encounter at this hour and in this place had every prospect of being a dangerous one.

‘Who goes there?’ said Gautier.

They heard a second whistle, and had barely time to draw their daggers.

Six men surged out of the night and hurled themselves upon them. Three attacked Philippe and, holding him back to the wall with arms outstretched, prevented his using his dagger. The other three were not so fortunate with Gautier. The latter had managed to knock one of his attackers down or, more exactly, the man had slipped in trying to avoid a dagger-thrust. But the other two caught Gautier d’Aunay from behind and twisted his wrist till he dropped his weapon. Philippe could feel that they were trying to take his purse from him.

It was impossible to shout for help. If the guard from the Hôtel-de-Nesle came to their aid, they might be questioned about their presence there. They both had the same instinct not to shout. They must get out of it by themselves, or not get out of it at all.

Philippe, spread-eagled against the wall, fought with all the violence of despair, and, since he could not use his dagger, kicked out with his feet. He did not want to lose his purse. It had suddenly become his most precious possession in the world, and he intended to save it at all costs. Gautier was more inclined to come to terms. Let them take their money but leave them their lives. The point was, would they leave them their lives, or would they rob them first and throw their bodies into the Seine afterwards?

It was at this moment that another shadow appeared out of the night. Gautier, who had not at first seen it, had no time to make up his mind whether it was friend or foe.

Everything happened very quickly.

One of the assailants cried, ‘Watch out! Watch out!’

The new arrival rushed into the middle of the fight like a lion, the light shining on his drawn sword.

‘Thieves! Scoundrels! Knaves!’ he cried in a powerful voice as he distributed a shower of blows about him.

The thieves disappeared like flies before his attack. As one of the cut-throats passed within reach of his hand, he took him by the collar and hurled him against the wall. The whole gang decamped along the river bank without asking for more. They could be heard running towards the Petit-Pré-aux-Clercs, and then there was silence.

Gasping and stumbling, his hands clasped to his chest, Philippe went over to his brother.

‘Are you hurt?’ he asked.

‘No,’ said Gautier breathlessly, rubbing his shoulder. ‘And you?’

‘Nor am I. But it’s a miracle to have got away with it.’

Together they turned towards the stranger who, for the last few seconds, had been chasing the thieves and was now returning, putting up his sword. He looked very tall, broad and strong; his breath came deep and fierce.

‘Well, Messire,’ said Gautier, ‘we’re very grateful to you. Without your help we should soon have been floating down the river. To whom have we the honour to be beholden?’

The man laughed, a great, fat, rather forced laugh. One could imagine his strong, pointed teeth in the darkness. For an instant the two brothers thought that they recognised the laugh, then the moon came out from behind the clouds and they knew their defender.

‘By heaven, Monseigneur, it’s you, is it!’ cried Philippe.

‘And by heaven, young sirs,’ replied the man, ‘I know you too!’

They had been saved by Robert of Artois.

‘The brothers Aunay!’ he cried. ‘The handsomest young fellows at Court. Devil take it, I didn’t expect that. I was just passing along the bank when I heard the row down here, and said to myself, “There’s some peaceable townsman getting done in!” I must say, Paris is infested with these rogues, and that fool of a Provost is too busy licking Marigny’s boots to attend to cleaning up the town.’

‘Monseigneur,’ said Philippe, ‘we don’t know how to thank you.’

‘It’s nothing,’ said Robert of Artois, patting Philippe on the shoulder with a hand that made him reel. ‘It’s a pleasure! It’s every gentleman’s natural instinct to go to the assistance of someone in danger. But it’s a double pleasure if that someone is of one’s acquaintance, and I am delighted to have preserved for my cousins of Valois and Poitiers their best equerries. It’s only a pity it was so dark. By heaven, if the moon had only come out sooner I should have taken great pleasure in ripping up some of those rascals. I didn’t really dare thrust properly for fear of wounding you. But, tell me young gentlemen, what the devil are you doing in this dirty hole?’

‘We … we were taking a walk,’ said Philippe d’Aunay, embarrassed.

The giant roared with laughter.

‘Oh, so you were taking a walk, were you? A fine place and a fine hour for a walk! You were taking a walk in mud up to your knees! That’s a likely story! Ah, youth! This is a little matter of some love affair, isn’t it? A question of women,’ he said jovially, crushing Philippe’s shoulder once more. ‘Always on heat, eh! What it is to be your age!’

He suddenly saw their purses shining in the moonlight.

‘Christ!’ he cried. ‘On heat and to good purpose! Fine ornaments, young gentlemen, fine ornaments!’

He tried the weight of Gautier’s purse.

‘Gold thread, and fine work. Italian or English maybe. Equerries’ salaries don’t run to this sort of splendour. The cut-throats would have had a good haul.’

He grew excited, gesticulated, banged the young men about with friendly blows of his fist, enormous, noisy, red-headed and obscene in the half-light. He was beginning to get seriously on the brothers’ nerves. But how do you tell a man who has just saved your life to mind his own business?

‘Love obviously pays, my fine young sirs,’ he said walking beside them. ‘Your mistresses must be very great ladies and very generous ones. Good God, you young Aunays, who would have thought it, eh!’

‘Monseigneur is in error,’ said Gautier rather coldly. ‘These purses came to us through the family.’

‘Of course they do, I knew it,’ said Artois, ‘from a family you’ve visited at midnight under the walls of the Tower of Nesle! Quite, quite, I shan’t say anything, honour comes first. I approve of you, young sirs. One must respect the reputation of the women one sleeps with! All right. Good-bye. And don’t venture out at night wearing all your jewellery again.’

He went off into another great gale of laughter. With a huge gesture of embracing them, he banged the two brothers one against the other, and then went off, leaving them there, anxious and disquieted, without even giving them time to repeat their thanks.

They were at the Porte de Bucy and went on their way to the right, while Artois went off through the fields in the direction of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

‘I hope to God he doesn’t go telling all the Court where he found us,’ said Gautier. ‘Do you think he’s capable of keeping his great mouth shut?’

‘Yes,’ said Philippe. ‘He’s not a bad sort of chap. And the proof is that without his great mouth, as you call it, and his great arms for that matter, we shouldn’t be here now. Don’t let’s be ungrateful, not yet anyway.’

‘That’s true. Besides, we might have asked him what the hell he was doing there anyway.’