По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

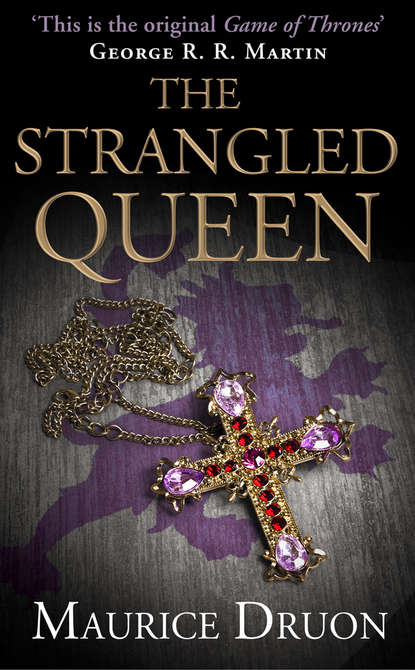

The Strangled Queen

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hardly had his hands grown cold, hardly had the great power of his will become extinguished, than private interest, disappointed ambition, and the thirst for honours and wealth began to proclaim their presence.

Two parties were in opposition, battling mercilessly for power: on the one hand, the clan of the reactionary Barons, at its head the Count of Valois, titular Emperor of Constantinople and brother of Philip the Fair; on the other, the clan of the high administration, at its head Enguerrand de Marigny, first Minister and Coadjutor of the dead king.

A strong king had been required to avoid or hold in balance the conflict which had been incubating for many months. And now the twenty-five-year-old prince, Monseigneur Louis, already King of Navarre, who was succeeding to the throne, seemed ill-endowed for sovereignty; his reputation was that, merely, of a cuckolded husband and whatever could be learned from his melancholy nickname of The Hutin, The Headstrong.

His wife, Marguerite of Burgundy, the eldest of the Princesses of the Tower of Nesle, had been imprisoned for adultery, and her life was, curiously enough, to be a stake in the interplay of the rival factions.

But the cost of faction, as always, was to be the misery of the poor, of those who lacked even the dreams of ambition. Moreover, the winter of 1314–15 was one of famine.

PART ONE

THE DAWN OF A REIGN

1

The Prisoners of Château-Gaillard

BUILT SIX HUNDRED FEET up upon a chalky spur above the town of Petit-Andelys, Château-Gaillard both commanded and dominated the whole of Upper Normandy.

At this point the river Seine describes a large loop through rich pastures; Château-Gaillard held watch and ward above the river for twenty miles up and down stream.

Today the ruins of this formidable citadel can still startle the eye and defy the imagination. With the Krak des Chevaliers in the Lebanon, and the towers of Roumeli-Hissar on the Bosphorus, it remains one of the most imposing relics of the military architecture of the Middle Ages.

Before these monuments, constructed to make conquest good or threaten empire, the imagination is obsessed by the men, separated from us by no more than fifteen or twenty generations, who built them, used them, lived in them, and sacked them.

At the period of this story, Château-Gaillard was no more than a hundred and twenty years old. Richard Cœur-de-Lion had built it in two years, in defiance of treaties, to defy the King of France. Seeing it finished, standing high upon its cliff, its freshly hewn stone white upon its two curtain walls, its outer works well advanced, its portcullises, battlements, thirteen towers, and huge, two-storied keep, he had cried: ‘Oh, what a gallant [gaillard] castle!’

Ten years later Philip Augustus took it from him, together with the whole land of Normandy.

Since then Château-Gaillard had no longer served a military purpose and had become a royal prison.

Important state criminals were confined there, prisoners whom the King wished to preserve alive but incarcerate for life. Whoever crossed the drawbridge of Château-Gaillard had little chance of ever re-entering the world.

By day crows croaked upon its roofs; by night wolves howled beneath its walls. The only exercise permitted the prisoners was to walk to the chapel to hear Mass and return to their tower to await death.

Upon this last morning of November 1314, Château-Gaillard, its ramparts and its garrison of archers were employed merely in guarding two women, one of twenty-one years of age, the other of eighteen, Marguerite and Blanche of Burgundy, two cousins, both married to sons of Philip the Fair, convicted of adultery with two young equerries and condemned to life-imprisonment as the result of the most resounding scandal that had ever burst upon the Court of France.

The chapel was inside the inner curtain wall. It was built against the natural rock; its interior was dark and cold; the walls had few openings and were unadorned.

Before the choir were placed three seats only: two on the left for the Princesses, one on the right for the Captain of the Fortress.

At the rear of the chapel the men-at-arms stood in their ranks, manifesting an air of boredom similar to the one they wore when engaged upon the fatigue of foraging.

‘My brothers,’ said the Chaplain, ‘today we must pray with peculiar fervour and solemnity.’

He cleared his throat and hesitated a moment, as if concerned at the importance of what he had to announce.

‘The Lord God has called to himself the soul of our much-beloved King Philip,’ he went on. ‘This is a profound tragedy for the whole kingdom.’

The two Princesses turned towards each other faces shrouded in hoods of coarse brown cloth.

‘May those who have done him injury or wrong repent of it in their hearts,’ continued the Chaplain. ‘May those who had some grievance against him when he was alive, pray for that mercy for him of which every man, great or small, has equal need at his death before the tribunal of our Lord …’

The two Princesses had fallen on their knees, bending their heads to hide their joy. No longer did they feel the cold, no longer the pain and grief; a great surge of hope rose within them; and had the idea of praying to God crossed their minds, it would but have been to thank Him for delivering them from their terrible father-in-law. It was the first good news that had reached them from the outside world in all the seven months of their imprisonment in Château-Gaillard.

The men-at-arms, at the back of the chapel, whispered together, questioning each other in low voices, shuffling their feet, beginning to make too much noise.

‘Shall we be given a silver penny each?’

‘Why, because the King is dead?’

‘It’s usual, at least I’m told so.’

‘No, you’re wrong, not for his death; only, perhaps, for the coronation of the next one.’

‘And what’s the new king going to call himself?’

‘Monsieur Saint Louis was the ninth; obviously this one will call himself Louis X.’

‘Do you think he’ll go to war so that we can move around a bit?’

The Captain of the Fortress turned about and shouted harshly, ‘Silence!’

He too had his worries. The elder of the prisoners was the wife of Monseigneur Louis of Navarre, who was to become king today. ‘So I am now in the position of being gaoler to the Queen of France,’ he thought.

Being goaler to royal personages can never be a situation of much comfort; and Robert Bersumée owed some of the worst moments of his life to these two convicted criminals who had arrived, their heads shaven, towards the end of April, in black-draped wagons, escorted by a hundred archers under the command of Messire Alain de Pareilles. What anxiety and worry he had endured to set against the paltry satisfaction of his vanity! They were two young women, so young that he could not help pitying them despite their sin. They were too beautiful, even beneath their shapeless robes of rough serge, for it to be possible to avoid some emotion at the sight of them day after day for seven months. Supposing they seduced some sergeant of the garrison, supposing they escaped, or one of them hanged herself, or they succumbed to some fatal disease, or again supposing their fortunes revived – for could one ever tell what might not happen in Court affairs? It would be he who was always in the wrong, culpable of being too harsh or too weak, and none of it would help him to promotion. Moreover, like the Chaplain, the prisoners and the men-at-arms themselves, he had no wish to finish his days and his career in a fortress battered by the winds, drenched by the mists, built to accommodate two thousand soldiers and which now held no more than one hundred and fifty, above a valley of the Seine from which war had long ago retreated.

‘The Queen of France’s gaoler,’ the Captain of the Fortress repeated to himself; ‘it needed but that.’

No one was praying; everyone pretended to follow the service while thinking only of himself.

‘Requiem æternam dona eis domine,’ the Chaplain intoned.

He was thinking with fierce jealousy of priests in rich chasubles at that moment singing the same notes beneath the vaults of Notre-Dame. A Dominican in disgrace, who had, upon taking orders, dreamed of being one day Grand Inquisitor, he had ended as a prison chaplain. He wondered whether the change of reign might bring him some renewal of favour.

‘Et lux perpetua luceat eis,’ responded the Captain of the Fortress, envying the lot of Alain de Pareilles, Captain-General of the Royal Archers, who marched at the head of every procession.

‘Requiem æternam … So they won’t even issue us with an extra ration of wine?’ murmured Private Gros-Guillaume to Sergeant Lalaine.

But the two prisoners dared not utter a word; they would have sung too loudly in their joy.

Certainly, upon that day, in many of the churches of France, there were people who sincerely mourned the death of King Philip, without perhaps being able to explain precisely the reasons for their emotion; it was simply because he was the King under whose rule they had lived, and his passing marked the passing of the years. But no such thoughts were to be found within the prison walls.

When Mass was over, Marguerite of Burgundy was the first to approach the Captain of the Fortress.

‘Messire Bersumée,’ she said, looking him straight in the eye, ‘I wish to talk with you upon matters of importance which also concern yourself.’

The Captain of the Fortress was always embarrassed when Marguerite of Burgundy looked directly at him and on this occasion he felt even more uneasy than usual.