По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

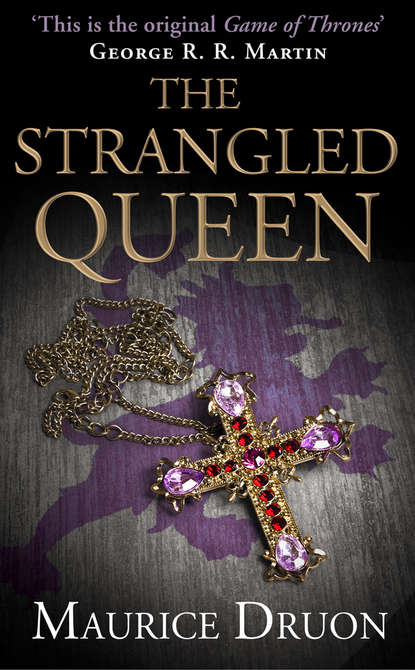

The Strangled Queen

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well,’ went on her visitor, ‘this is what Monseigneur Valois has devised to get his nephew out of his difficulty.’

He paused and cleared his throat.

‘You will admit that your daughter, the Princess Jeanne, is not Louis’s child; you will admit that you have never slept with your husband and that there has therefore never been a true marriage. You will declare this voluntarily in the presence of myself and your chaplain as supporting witnesses. Among your previous servants and household there will be no difficulty in finding witnesses to testify that this is the truth. Thus the marriage will have no defence and the annulment will be automatic.’

‘And what am I offered in exchange for this lie?’ asked Marguerite.

‘In exchange for your cooperation,’ replied Artois, ‘you are offered safe passage to the Duchy of Burgundy, where you will be placed in a convent until the annulment has been pronounced, and thereafter to live as you please or as your family may desire.’

On first hearing, Marguerite very nearly answered, ‘Yes, I accept; I declare all that is desired of me; I will sign no matter what, on condition that I may leave this place.’ But she saw Artois watching her from under lowered lids, a gaze ill-matched with his good-natured air; and intuitively she knew that he was tricking her. ‘I shall sign,’ she thought, ‘and then they will continue to keep me here.’

Duplicity in the heart is catching. But in fact Artois was for once telling the truth; he was the bearer of an honest proposal; he even had the order with him for Marguerite’s removal, should she consent to the declaration required of her.

‘It is asking me to commit a grave sin,’ she said.

Artois burst out laughing.

‘Good God, Marguerite,’ he cried, ‘it seems to me you have committed others with less scruple!’

‘Perhaps I have altered and repented. I must think the matter over before deciding.’

The giant made a wry face, twisting his lips from side to side.

‘Very well, Cousin, but think quickly,’ he said, ‘because I must be back in Paris tomorrow for the funeral mass at Notre-Dame. With fifty-eight miles in the saddle, even by the shortest way, and roads a couple of inches deep in mud, and daylight fading early and dawning late, and the delay for a relay of horses at Nantes, I have no time to dawdle and would much prefer not to have come all this way for nothing. Goodbye; I shall go and sleep an hour and come back to eat with you. It must not be said that I left you alone, Cousin, the first day upon which you fare well. I am sure you will have reached the right decision.’

He left like a whirlwind, as he had arrived, for he paid as much attention to his exits as his entrances, and nearly upset Private Gros-Guillaume in the staircase, as he came up bending and sweating under a huge coffer.

Then he disappeared into the Captain’s denuded lodging and threw himself upon the one couch that still remained.

‘Bersumée, my friend, see that dinner is ready in an hour’s time,’ he said. ‘And call my valet Lormet, who must be with the horsemen. Tell him to come and watch over me while I sleep.’

For this Hercules feared nothing but to be found defenceless by his numerous enemies while he slept. And he preferred to any squire or equerry the guardianship of this short, squat, greying servant who followed him everywhere for the apparent purpose of handing him his coat or cloak.

Unusually vigorous for his fifty years, all the more dangerous for his mild appearance, capable of anything in the service of ‘Monseigneur Robert’, and above all of obliterating noiselessly in a few seconds people who were an embarrassment to his master, Lormet, purveyor of girls on occasion and a great recruiter of roughs, was a rogue less by nature than from devotion; a killer, he had the affection of a wet-nurse for his master.

Shy, and a clever deceiver of fools, he was an able spy. Not the least of his exploits was to have led the brothers Aunay into a trap, so that they might be taken by Robert of Artois almost in flagrante delicto at the foot of the Tower of Nesle.

When Lormet was asked why he was so attached to the Count of Artois, he shrugged his shoulders and replied grumblingly, ‘Because from each of his old coats I can make two for myself.’

As soon as Lormet entered the Captain’s lodging, Robert closed his eyes and fell asleep upon the instant, his arms and legs stretched wide, his chest rising and falling with the deep breathing of an ogre.

An hour later he awoke of his own accord, stretched himself like a huge tiger, stood upright, his muscles and his mind refreshed.

Lormet was sitting on a bench, his dagger on his knees. Round-headed and narrow-eyed, he looked tenderly upon his master’s awakening.

‘Now it’s your turn to go and sleep, my good Lormet,’ said Artois; ‘but before you do, go and find me the Chaplain.’

3

Shall She be Queen?

THE DISGRACED DOMINICAN CAME at once, much agitated at being sent for personally by so important a lord.

‘Brother,’ Artois said to him, ‘you must know Madame Marguerite well, since you are her confessor. In what lies the weakness of her character?’

‘The flesh, Monseigneur,’ replied the Chaplain, modestly lowering his eyes.

‘We know that already! But in what else? Has her nature no emotional facet, no side upon which we can bring pressure to bear to force her to accept a certain course, which is not only to her own interest but to that of the kingdom?’

‘I can see nothing, Monseigneur. I can see no weakness in her except upon the one point I have already mentioned. The Princess’s spirit is as hard as a sword and even prison has not blunted its edge. Oh, believe me, she is no easy penitent!’

His hands in his sleeves, his broad brow bent, he was trying to appear both pious and clever at once. His tonsure had not been renewed for some time, and the skin of his skull showed blue above the thin circle of black hair.

Artois remained thoughtful for a moment, scratching his cheek because the Chaplain’s skull made him think of his beard which was beginning to grow.

‘As to the subject you have mentioned,’ he went on, ‘what has she found here in satisfaction of her particular weakness, since that appears to be the term you use for that form of vitality.’

‘As far as I know, none, Monseigneur.’

‘Bersumée? Does he ever visit her for rather over-long periods?’

‘Never, Monseigneur, I can vouch for that.’

‘And what about yourself?’

‘Oh! Monseigneur!’ cried the Chaplain, crossing himself.

‘All right, all right!’ said Artois. ‘It would not be the first time that such things have been known to happen, one is acquainted with more than one member of your cloth who, his soutane removed, feels himself to be a man like another. For my part I see nothing wrong in it: indeed, to tell you the truth, I see in it matter for praise rather. What of her cousin? Do the two women console each other from time to time?’

‘Oh! Monseigneur!’ said the Chaplain, pretending to be more and more horrified. ‘What you are asking me could only be a secret of the confessional.’

Artois gave the Chaplain’s shoulder a little friendly slap which nearly sent him staggering to the wall for support.

‘Now, now, Messire Chaplain, don’t be ridiculous,’ he cried. ‘If you have been sent to a prison as officiating priest, it is not in order that you should keep such secrets, but that you should repeat them to those authorized to hear them.’

‘Neither Madame Marguerite, nor Madame Blanche,’ said the Chaplain in a low voice, ‘have ever confessed to me of being culpable of anything of the kind, except in dreams.’

‘Which does not prove that they are innocent, but merely that they are secretive. Can you write?’

‘Certainly, Monseigneur.’

‘Well, well!’ said Artois with an air of astonishment. ‘Apparently all monks are not so damned ignorant as is generally supposed! Very well, Messire Chaplain, you will take parchment, pens, and everything you need to scratch down words, and you will wait at the base of the Princesses’ tower, ready to come up when I call you. You will make as much haste as you can.’

The Chaplain bowed; he seemed to have something more to say, but Artois had already donned his great scarlet cloak and was on his way out. The Chaplain hurried out behind him.

‘Monseigneur! Monseigneur!’ he said in a very obsequious voice. ‘Would you have the very great kindness, if I am not offending you by making such a request, would you have the immense kindness to say to Brother Renaud, the Grand Inquisitor, if it should so happen that you should see him, that I am still his obedient son, and ask him not to forget me in this fortress for too long, where indeed I do my duty as best I may since God has placed me here, but I have certain capacities, Monseigneur, as you have seen, and I much desire that they should be found other employment.’

‘I shall remember to do so, my good fellow, I shall remember,’ replied Artois, who already knew that he would do nothing about it whatever.