По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

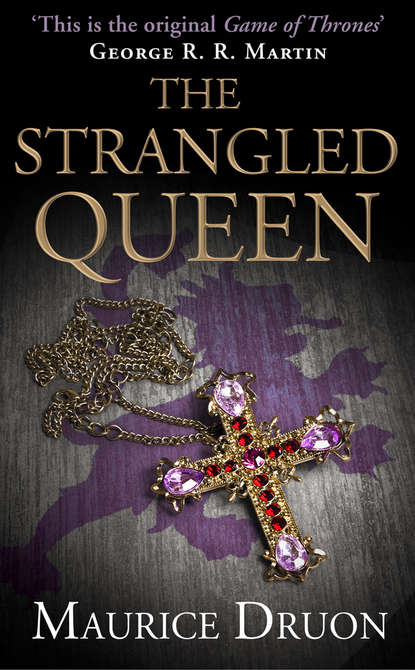

The Strangled Queen

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When Robert entered Marguerite’s room, the two Princesses had not quite finished dressing; they had washed lengthily before the fire with the warm water and the soapwort which had been brought them, making the restored pleasure last as long as possible; they had washed each other’s short hair, now still pearly with drops of water, and had newly clothed themselves in long white shirts, closed at the neck by a running string, which had been provided. For a moment they were afflicted with modesty.

‘Well, Cousins,’ said Robert, ‘you have no need to worry. Stay as you are. I am a member of the family; besides, those shirts you are wearing are more completely concealing than the dresses you used once to appear in. You look like a couple of little nuns. But you already look better than a while ago, and your complexions are beginning to revive. Admit that your living conditions have quickly altered with my coming.’

‘Oh, yes indeed and thank you, Cousin!’ cried Blanche.

The room was quite changed in appearance. A curtained bed had been brought, as well as two big chests which acted as benches, a chair with a back to it, and a trestle table upon which were already placed bowls, goblets and Bersumée’s wine. A tapestry with a faded design had been hung over the dampest part of the curved wall. A thick taper, brought from the sacristy, was alight upon the table, for though the afternoon had barely begun, daylight was already waning; and upon the hearth under the cone-shaped overmantel huge logs were burning, the damp escaping from their ends with a singing noise of bursting bubbles.

Immediately behind Robert, Sergeant Lalaine entered with Private Gros-Guillaume and another soldier, bringing up a thick, smoking soup, a large white loaf, round as a pie, a five-pound pasty in a golden crust, a roast hare, a stuffed goose and some juicy pears of a late species, which Bersumée, upon threatening to sack the town, had been able to extract from a greengrocer of Andelys.

‘What,’ cried Artois, ‘is that all you’re giving us, when I asked for a decent dinner?’

‘It’s a wonder, Monseigneur, that we have been able to find as much as we have in this time of famine,’ replied Lalaine.

‘It’s a time of famine, perhaps, for the poor, who are idle enough to expect the earth to produce without being tilled, but not for the wealthy,’ replied Artois. ‘I have never sat down to so poor a dinner since I was weaned!’

The prisoners gazed like young famished animals upon the food which Artois, the better to make the two women aware of their lamentable condition, affected to despise. There were tears in Blanche’s eyes. And the three soldiers gazed at the table with a wondering covetousness.

Gros-Guillaume, who subsisted entirely on boiled rye, and normally served the Captain’s dinner, went hesitatingly to the table to cut the bread.

‘No, don’t touch it with your filthy hands,’ shouted Artois. ‘We’ll cut it ourselves. Go on, get out, before I lose my temper!’

He could have sent for Lormet, but his guard’s slumber was one of the few things Robert respected. Or he could have sent for one of the horsemen, but he preferred to proceed without witnesses.

As soon as the archers had gone, he said in that facetious tone of voice still assumed by the rich today when by chance they have to carry a dish or wash a plate, ‘I shall get accustomed to prison life myself. Who knows,’ he added, ‘perhaps one day, my dear Cousin, you will be putting me in prison?’

He made Marguerite sit on the chair with the back.

‘Blanche and I will sit on this bench,’ he said.

He poured out the wine, raised his goblet towards Marguerite, and cried, ‘Long live the Queen!’

‘Don’t mock me, Cousin,’ said Marguerite. ‘It is lacking in charity.’

‘I am not mocking you; you can take my words literally. As far as I know, you are still Queen this day, and I wish you a long life, that’s all.’

Silence fell upon them, for they set about eating. Anyone but Robert might have been moved by the sight of the two women attacking their food like paupers.

At first they had tried to feign a dignified detachment, but hunger carried them away and they hardly gave themselves time to breathe between mouthfuls.

Artois spiked the hare upon his dagger and held it to the embers of the hearth to warm it. While doing so, he continued to watch his cousins, and had difficulty in controlling his laughter. ‘I’ve a good mind to put their bowls on the ground and let them get down on all fours and lick the very grain of the wood clean,’ he thought.

They drank too. They drank Bersumée’s wine as if they needed to compensate all at once for seven months of cistern-water, and the colour came back to their cheeks. ‘They’ll make themselves sick,’ thought Artois, ‘and they’ll finish this happy day spewing up their guts.’

He himself ate like a whole company of soldiers. His prodigious appetite was far from being a myth, and each mouthful would have needed dividing into four to suit an ordinary gullet. He devoured the stuffed goose as if it were a thrush, champing the bones. He modestly excused himself for not doing as much for the hare’s carcass.

‘Hare’s bones,’ he explained, ‘break into splinters and tear the stomach.’

When they had all eaten enough, he caught Blanche’s eye and indicated the door. She rose without being asked, though her legs were trembling under her; she felt giddy and badly wanted to go to bed. Then Robert had the first humanitarian impulse since his arrival. ‘If she goes out into the cold in this state, she’ll die of it,’ he said to himself.

‘Have they lighted a fire in your room?’ he asked.

‘Yes, thank you, Cousin,’ replied Blanche. ‘Our life …’

She was interrupted by a hiccough.

‘… our life is really quite altered thanks to you. Oh, how fond I am of you, Cousin, really fond indeed. You’ll tell Charles, won’t you? You will tell him that I love him. Ask him to forgive me because I love him.’

At the moment she loved everyone. She went out, quite drunk, and tripped upon the staircase. ‘If I were here merely for my own amusement,’ thought Artois, ‘I should meet with little resistance from that one. Give a princess enough wine, and you’ll soon see that she turns into a whore. But the other one seems to me pretty tight too.’

He threw a big log on the fire, turned Marguerite’s chair towards the hearth, and filled the goblets.

‘Well, Cousin,’ he asked, ‘have you thought things over?’

‘I have thought, Robert, I have thought. And I think I am going to refuse.’

She said this very softly. Apparently overcome as much by the warmth as by the wine, she was gently shaking her head.

‘Cousin, you’re not being sensible, you know!’ cried Robert.

‘But indeed, indeed, I think I shall refuse,’ she replied in an ironic, sing-song voice.

The giant made a gesture of impatience. ‘Listen to me, Marguerite,’ he went on. ‘It must be to your advantage to accept now. Louis is by nature an impatient man, ready to grant almost anything to get his own way at the moment. You will never again have the chance of doing so well for yourself. Merely agree to make the declaration asked of you. There is no need for the matter to go before the Holy See; we can get a judgement from the episcopal tribunal of Paris, which is under the jurisdiction of Monseigneur Jean de Marigny, Archbishop of Sens, who will be told to make haste. In three months’ time you will have regained complete personal freedom.’

‘And if I won’t?’

She was leaning towards the fire, her hands extended before her. The running string which held together the collar of her long shirt had become unknotted and revealed most of her bosom to her cousin’s wandering eye; but she did not seem to care. ‘The bitch still has beautiful breasts,’ thought Artois.

‘And if I won’t?’ she repeated.

‘If you won’t, your marriage will be annulled anyway, my dear, because reasons can always be found for annulling a king’s marriage,’ replied Artois carelessly, intent upon the objects of his contemplation. ‘As soon as there is a Pope …’

‘Oh, is there still no Pope?’ cried Marguerite.

Artois bit his lips. He had made a mistake. He ought to have remembered that she was ignorant, prisoner as she was, of what all the world knew, that since the death of Clement V the conclave had not succeeded in electing a new Pope. He had revealed a useful weapon to his adversary. And he realized by the quickness of Marguerite’s reaction to the news that she was not as drunk as she pretended to be.

Having committed the blunder, he tried to turn it to his own advantage by playing that game of false frankness of which he was a master.

‘But that is exactly where your good fortune lies!’ he cried. ‘That is precisely what I want you to understand. As soon as those rascally cardinals, who sell their promises as if they were at auction, have made enough out of their votes to consent to agree, Louis will no longer have need of you. You will merely have succeeded in making him hate you all the more, and he’ll keep you shut up here for ever.’

‘Yes, but so long as there is no Pope, nothing can be done without my agreement.’

‘You’re foolish to be so obstinate.’

He went and sat next to her, placed his huge hand as gently as he could about her neck and began to stroke her shoulder.

Marguerite seemed troubled by the contact of his huge muscular hand. It was so long since she had felt a man’s hand upon her skin!

‘Why should you be so interested in my accepting?’ she asked.