По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

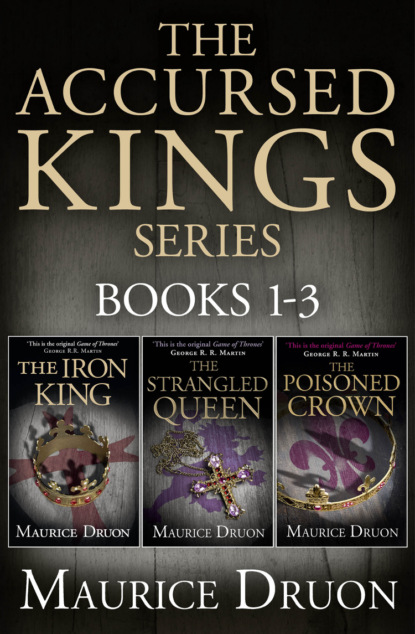

The Accursed Kings Series Books 1-3: The Iron King, The Strangled Queen, The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It is there I think things over,’ he had told his familiars one day when he was being particularly forthcoming.

Upon the table was a three-branched silver candelabra whose light fell upon a file of parchments which the King was reading and signing. Beyond the windows the park rustled in the twilight, and Isabella, looking out into the night, watched the dark absorb the trees one by one.

Since the time of Blanche of Castille, Maubuisson, on the borders of Pontoise, had been a royal residence and Philip had made it one of his regular country retreats. He liked the silence of the place, closed in as it was by high walls; he liked his park, his garden and his abbey in which Benedictine sisters lived out their peaceful lives. The castle itself was not very large, but Philip the Fair liked its quiet and preferred Maubuisson to all his greater houses.

Isabella had met her three sisters-in-law, Marguerite, Jeanne and Blanche, with a serenely smiling face, and had replied conventionally to their words of welcome.

Supper had soon been over. And now Isabella was alone with her father for the purpose of accomplishing the task, atrocious but necessary, upon which she was set. King Philip looked at her with that icy glance with which he regarded every human creature, even his own child. He was waiting for her to speak; and she did not dare.

‘I shall hurt him so much,’ she thought. And suddenly, because of his presence, because of the park, the trees and the silence, Isabella was a prey to a wave of childish memories and her throat constricted with bitter self-pity.

‘Father,’ she said, ‘Father, I am very unhappy. Oh! how very far away France seems since I have been Queen of England. And how I regret the days that are past!’

She found herself trying to fight an unexpected enemy: tears.

After a brief silence, without going to her, Philip the Fair asked gently but without warmth, ‘Was it to tell me this, Isabella, that you have undertaken the journey?’

‘And to whom should I admit my unhappiness if not to my father?’ she replied.

The King looked at the night beyond the gleaming panes of the window, then at the candles, then at the fire.

‘Happiness …’ he said slowly. ‘What is happiness, daughter, if it is not to conform to one’s destiny? If it is not learning to say yes, always to God … and often to men?’

They were sitting opposite each other on cushionless oak chairs.

‘It is true that I am a Queen,’ she said in a low voice. ‘But am I treated as a Queen over there?’

‘Are you done wrong by?’

But there was little surprise in the tone of his voice as he put the question. He knew only too well what she would answer.

‘Don’t you know to whom you have married me?’ she said with some force. ‘Can he be called a husband who deserted my bed from the very first day? From whom all my care, all my respect, all my smiles, cannot get a single word of response? Who shuns me as if I were ill and confers, not upon mistresses, but upon men, Father, upon men, the favours he denies me?’

Philip the Fair had known all this for a long time, and his reply had also been ready for a long time.

‘I did not marry you to a man,’ he said, ‘but to a King. I did not sacrifice you by mistake. I don’t have to tell you, Isabella, what we owe to our position and that we are not born to succumb to personal sorrows. We do not lead our own lives, but those of our kingdoms, and it is there alone that we can find content … if we conform to our destiny.’

He had drawn somewhat nearer to her while speaking and the light of the candle-flames etched the shadows upon his face, bringing his beauty into better relief, emphasising his air of always searching for self-conquest and being proud of it.

More than his words, the King’s expression and his beauty delivered Isabella from her weakness.

‘I could only have loved a man who was like him,’ she thought, ‘and I shall never love nor shall I ever be loved, because I shall never find a man in his likeness.’

Then, aloud, she said, ‘I am glad that you should have reminded me what I owe to myself. It is not to weep that I have come to France, Father. I am glad too that you have reminded me of the self-respect proper to people of royal birth, and that happiness for us must count for nothing. I only wish that everyone about you should think the same.’

‘Why did you come?’

She took a deep breath. ‘Because my brothers have married whores, Father, and I have discovered it, and because I am as anxious as you to uphold our honour.’

Philip the Fair sighed.

‘I know very well that you do not care for your sisters-in-law, but the difference between you …’

‘The difference between us is the difference between an honest woman and a whore!’ said Isabella coldly. ‘Wait a minute, Father! I know things that have been concealed from you. Listen to me, because I am not only bringing you words. Do you know the young Messire Gautier d’Aunay?’

‘There are two brothers whom I always confuse with each other. Their father was with me in Flanders. The one you mention married Agnes de Montmorency, didn’t he? And he is with my son, the Count of Poitiers, as equerry.’

‘He is also with your daughter-in-law, Blanche, but in another capacity. His younger brother Philippe, who is at my uncle of Valois’ house.’

‘Yes,’ said the King, ‘yes …’

A deep wrinkle, a very rare thing with him, showed upon his forehead.

‘Well, he is Marguerite’s, whom you have chosen to be one day Queen of France! As for Jeanne, she apparently has no lover, but this may merely be that she conceals the fact better than the others. At least it is known that she is a party to the pleasures of her sister and her cousin, that she covers the visits of the gallants to the Tower of Nesle, and appears to be adept at a profession which has a name all its own. And you may as well know that the whole Court talks of it, except you.’

Philip the Fair raised a hand.

‘Your proofs, Isabella?’

Isabella then told him about the purses.

‘You will find them at the belts of the brothers Aunay. I saw them myself upon the road. That is all I have to tell you.’

Philip the Fair looked at his daughter. It seemed that under his very eyes she had changed both in face and character. She had brought her accusation without hesitation, without weakening, and there she sat, upright in her chair, tight-lipped, with something stern and icy at the back of her eyes. She had not spoken from wickedness or jealousy, but from justice. She was in truth his daughter.

The King rose without replying. For a long moment he stood before the window, and still the long deep wrinkle showed upon his forehead.

Isabella did not move, awaiting the consequences of what she had unleashed, ready to give further proof.

‘Come,’ the King said suddenly. ‘Let us go to them.’

He opened the door, passed through a long dark corridor and pushed open a second door. Suddenly they were in the grip of the night wind, which made their full clothing flow out behind them.

The three daughters-in-law had apartments in the other wing of the Castle of Maubuisson. From the tower, where the King’s study was, their apartments were reached by a covered rampart. A guard dozed by each loophole, short gusts of wind shook the slates. From below the smell of damp earth rose up to them.

Without speaking, the King and his daughter followed the ramparts. Their feet rang out in time upon the stone, and every twenty yards an archer rose to his feet.

When they came to the door of the Princesses’ apartments, Philip the Fair paused for a moment. He listened. Laughter and little cries of pleasure came from beyond the door. He looked at Isabella.

‘It is necessary,’ he said.

Isabella nodded her head without replying, and Philip the Fair opened the door.

Marguerite, Jeanne and Blanche uttered a cry of surprise and their laughter came to an abrupt end.

They had been playing with marionettes and were amusing themselves by recapitulating a scene they had invented and which, produced by a master juggler, had much diverted them one day at Vincennes, but which had much irritated the King. The marionettes were made to resemble the principal personages of the Court. The little scene represented the King’s chamber, where he himself appeared sleeping in a bed covered with cloth of gold. Monseigneur of Valois knocked on the door and asked to speak to his brother. Hugues de Bouville, the Chamberlain, replied that the King could not receive him and had given instructions that no one was to disturb him. Monseigneur of Valois went away in a rage. Then the marionettes representing Louis of Navarre and his brother Charles knocked at the door in their turn. Bouville gave the same answer to the two sons of the King. At last, preceded by three sergeants-at-arms carrying maces, Enguerrand de Marigny presented himself; at once the door was opened wide and the Chamberlain said, ‘Monseigneur, you are welcome. The King much desires to speak with you.’

This satire upon the habits of the Court had very much annoyed Philip the Fair, who had forbidden a repetition of the play. But the three young Princesses paid no attention, and secretly amused themselves with it all the more because it was forbidden.