По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

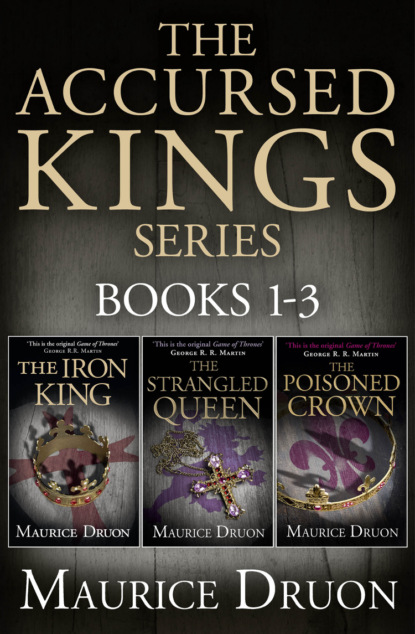

The Accursed Kings Series Books 1-3: The Iron King, The Strangled Queen, The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They varied the dialogue and improved upon it with new mockeries, particularly when they manipulated the marionettes which represented their husbands.

When the King and Isabella came in, they felt like schoolgirls caught out.

Marguerite quickly picked up a surcoat that lay on a chair and put it round her to hide her too-naked throat. Blanche smoothed back her hair which had become disarranged in simulating her uncle Valois in a rage.

Jeanne, who remained calmer than the others, said vivaciously, ‘We have just finished, Sire; we have just this moment finished, and you might have heard it all without there being anything to wound you. We shall tidy it all away.’

She clapped her hands.

‘Hallo, there! Beaumont, Comminges, my good women!’

‘There is no need to call your ladies,’ the King said curtly.

He had barely noticed their game; it was at them he was looking. Eighteen, nineteen and a half, twenty-three; all three pretty, each in her different way. He had watched them grow taller and more beautiful since they had come, each at the age of about twelve or thirteen, to marry one of his sons. But they did not seem to have grown more intelligent than they had been in those days. They still played with marionettes like disobedient little girls. Was it possible that what Isabella said was true? Was it possible that so much feminine wickedness could exist in these beings who seemed to him still children? ‘Perhaps,’ he thought, ‘I know nothing of women.’

‘Where are your husbands?’ he asked.

‘In the fencing-school, Sire,’ said Jeanne.

‘Look, I have not come alone,’ he went on. ‘You often say that your sister-in-law does not love you. And yet I am told that she has given you each a really handsome present.’

Isabella watched Marguerite’s and Blanche’s eyes fade, as if their brilliance had been doused.

‘Will you,’ Philip went on slowly, ‘show me the purses you received from England?’

The silence that followed seemed to separate the world into two parts. On one side was Philip the Fair, Isabella, the Court, the barons, the kingdom; and on the other were the Iron King’s three daughters-in-law, on the point of entering a realm of appalling nightmare.

‘Well?’ said the King. ‘Why this silence?’

He continued to look fixedly at them with his huge, unblinking eyes.

‘I have left mine in Paris,’ said Jeanne.

‘I too, I too,’ the others at once assented.

Slowly Philip the Fair went towards the door that gave upon the corridor, and the wood of the floorboards could be heard creaking beneath his feet. Lividly pale, the three young women watched his every movement.

No one looked at Isabella. She was leaning against the wall, at some distance from the hearth; her breath came quickly.

Without looking round, the King said, ‘Since you have left your purses in Paris, we shall ask the young Aunays to fetch them at once.’

He opened the door, called one of the guards and ordered him to fetch the two equerries.

Blanche’s resistance gave way. She let herself fall upon a stool, the blood had drained from her face, her heart seemed to have stopped, and her head fell to one side, as if she were about to fall prostrate upon the floor. Jeanne seized her by the small of the arm and shook her to make her regain control of herself. Marguerite was mechanically twisting in her little brown hands the neck of the marionette representing Marigny, with which she had been playing but a few moments before.

Isabella did not move. She saw the glances Marguerite and Jeanne cast upon her, looks of hatred which emphasised the role of informer she was playing, and suddenly she felt an enormous lassitude. ‘I shall play this out to the end,’ she thought.

The brothers Aunay came in, eager, confused, almost falling over each other in their desire to make themselves useful and to show their worth.

Without leaving the wall against which she was leaning, Isabella stretched out a hand and said only, ‘Father, these gentlemen seem to have divined your thought, since they have brought my purses attached to their belts.’

Philip the Fair turned towards his daughters-in-law.

‘Can you tell me how these equerries come to be wearing the presents that your sister-in-law gave you?’

None of them answered.

Philippe d’Aunay looked at Isabella in astonishment, like a dog that does not understand why he is being beaten, then turned his eyes towards his elder brother, looking for protection. Gautier’s mouth was hanging open.

‘Guards!’ cried the King.

His voice sent cold shivers down the spine of everyone present and echoed, strange and terrible, through the castle and the night. For more than ten years, since the battle of Mons-en-Pévèle to be exact, where he had rallied his army and forced a victory, the King had never been heard to shout. Indeed, everyone had forgotten that he might still have so powerful a voice. Moreover, it was the only word that he produced in this fashion.

‘Archers! Send for your captain,’ he said to the men who came running.

There was a sound of heavy feet and Messire Alain de Pareilles appeared, bare-headed, buckling on his belt.

‘Messire Alain,’ said the King, ‘seize these two men. Put them in a dungeon in irons. They will have to answer at the bar of justice for their felony.’

Philippe d’Aunay wished to rush forward.

‘Sire,’ he stammered, ‘Sire …’

‘Enough,’ said Philip the Fair. ‘It is to Messire de Nogaret that you must speak now. Messire Alain,’ he went on, ‘the Princesses will be guarded here by your men till further orders. They are forbidden to go out. No one whatever, neither servants, relations, nor even their husbands, may enter here or speak to them. You will answer to me for any breach of these orders.’

However surprising the orders sounded, Alain heard them without flinching. The man who had arrested the Grand Master of the Templars could no longer be surprised by anything. The King’s will was his only law.

‘Come on, Messires,’ he said to the brothers Aunay, pointing to the door. And he ordered his archers to carry out the instructions he had received.

As they went out, Gautier murmured to his brother, ‘Let us pray, brother, because this is the end.’

And then their footsteps, lost amid those of the men-at-arms, sounded upon the stone flags.

Marguerite and Blanche listened to the sound of the footsteps dying away. Their lovers, their honour, their fortune, all their lives were going with them. Jeanne wondered whether she would ever manage to exculpate herself. With a sudden movement, Marguerite threw the marionette she was holding into the fire.

Once more Blanche was on the point of fainting.

‘Come, Isabella,’ said the King.

They went out. The Queen of England had won; but she felt tired and strangely moved because her father had said, ‘Viens, Isabelle.’ It was the first time he had addressed her in the second person since she was a small child.

Following one another, they went back the way they had come. The east wind chased huge dark clouds across the sky. Philip left Isabella at the door of her apartments and, taking up a silver candelabra, went to find his sons.

His tall shadow and the sound of his footsteps awoke the guards in the deserted galleries. His heart felt heavy in his breast. He did not feel the drops of hot wax that fell upon his hand.

8 (#ulink_bb541ed9-369b-5539-9e60-fb2695d6a0fc)

Mahaut of Burgundy (#ulink_bb541ed9-369b-5539-9e60-fb2695d6a0fc)