По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

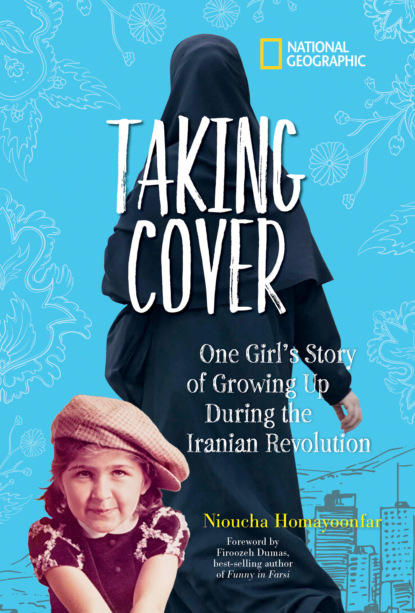

Taking Cover: One Girl's Story of Growing Up During the Iranian Revolution

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She hadn’t done that in years, but I felt relieved to have her there with me.

The next day, most teachers, including mine, didn’t come to school. With so few teachers present, the principal announced over the loudspeaker: “Good morning, children. Because of the unusual circumstances we find ourselves in today, so long as you behave yourselves, you are free to play games or study until your parents pick you up.”

—

Hearing the principal’s voice brought me back to my first day of school in Iran, three years earlier. I had stood outside my firstgrade classroom crying, clutching Baba’s hand and begging him not to leave. Dozens of children filled the courtyard and played under the large willow trees.

My new school was called Razi. It was for French-Iranian kids like me, or for Iranian kids who wanted to have a dual-language education. We had been given a tour of it when we came for registration. I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was the biggest school I had ever seen.

Before moving to Iran we lived in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At the time of my school tour we had been in Iran only a few weeks. Back in Pittsburgh, Baba had explained to me that he wanted to live near his family, that he missed his homeland. I was sad to leave the friends I had made in my preschool class. My preschool was in a room at the back of a church in our neighborhood.

By contrast, Razi had a large swimming pool, four tennis courts, a track field, a gymnasium, and a theater. The school was divided into several areas for preschool, kindergarten, elementary, middle, and high school. As soon as the bell rang, the children rushed into their classes, leaving Baba and me alone in the concrete hallway. With a gentle nudge toward the classroom, Baba said, “I’ll wait right outside this door until recess, all right?”

“But I don’t belong here!” I said.

“Nioucha, we’ve gone over this. You do belong here. Now go on.”

Reluctantly, I picked up the schoolbag at my feet and flung it over my shoulder. Baba pulled out his handkerchief, the one he used for wiping his glasses and his balding head. Gently he dried my tears and runny nose, being careful not to drop the newspaper and book tucked under his left arm.

I sniffled deeply and gave Baba one last pleading glance. It had worked so well with him before, but not this time. He smiled, turned me around, and gave me a light but firm push. I walked into class and took my assigned seat in the front row.

Mrs. Darvish opened her large notebook and began roll call.

“Anahita A., Jean-Louis D., Bianca G.”

She checked off names with a red marker and nodded curtly to each student after they called out, “Yes” in Persian, the language of Iran.

“Nioucha H.,” she said.

I knew she was looking at me through her thick glasses, but I kept staring at my desk and fingering the strap of my schoolbag.

“Nioucha,” she repeated, this time raising her voice.

I shared a school bench with Anahita. She elbowed me and whispered, “Say baleh.“

I didn’t want to.

Mrs. Darvish exhaled loudly and scribbled something in her notebook. When she finished calling everyone’s name, she rose from her seat. She smoothed her pleated black skirt and turned it around to make sure the seams were placed properly on her ample hip bones.

She took a piece of blue chalk and said, “Is class ready for their lesson?”

She smiled and her glasses moved up against her forehead.

“Yes, Mrs. Darvish,” the classroom answered.

She turned her back to us and began to write on the blackboard. All the kids in class took out their notebooks and pencils, ready to copy what the teacher wrote. Except me. I slipped my hands under my legs and rocked myself on the bench.

Anahita whispered, “Why aren’t you doing anything?”

“Because I don’t want to,” I whispered back.

“But you’ll get in trouble,” she warned.

“Don’t worry about me,” I said.

She shrugged and returned to her notebook, her long braid swinging down her shoulder.

I glanced up and stared at the photo of the shah and his wife, Farah, displayed above the blackboard. They were the king and queen of Iran. In the picture, he wore a uniform with lots of medals, and she had on a gorgeous crown made of diamonds and pearls. They smiled down at us as if to say, “We are watching over you as you study.”

I looked at the clock, wishing I knew how to read it. I understood Baba’s digital watch because he’d taught me how it worked, but this one had the little arm and the big arm that confused me. I wondered how much longer it would be before the bell would ring and I could meet Baba. He hadn’t started his job yet, but Maman had, so he was the one bringing me to school. The first two days I had cried so much that Mrs. Darvish had let me leave so I could sit with him just outside the classroom.

My eyes wandered to the posters by the door: rows of animals and fruits with the name next to each one. The animal poster had a picture of a yellow-and-blue canary, and I kept staring at him, willing him to fly out and sit on my finger like Titi, the canary I had in Pittsburgh, used to do.

Suddenly, Mrs. Darvish was standing directly in front of me.

“What are you waiting for?” she said. “Start working! You’re supposed to practice writing alef.“

I followed her finger to where it pointed at the blackboard.

“Anahita,” Mrs. Darvish said, “tell Nioucha about alef.”

“Alef is the first letter of the alphabet,” she answered.

“Very good,” Mrs. Darvish said. Then to me, “So why aren’t you working?”

“Because I’m not Iranian,” I said. “I am French.”

“You are both,” Mrs. Darvish said. “And you are speaking Persian even though you’re pretending not to understand me.”

I sat staring straight ahead, thinking she’d eventually grow tired and walk back to her desk.

“Do you behave this way with Madame Martine in the afternoons too?” Mrs. Darvish continued.

“No,” Anahita said. “Nioucha is a good student in Madame Martine’s class.”

Mrs. Darvish didn’t like hearing this. Her eyebrows furrowed even more.

She leaned down, and through clenched teeth said, “Nioucha, if you don’t start writing this minute, I’ll break your hand.”

Anahita gasped. I knew from how quiet the classroom grew that all the kids were staring at the teacher and me. My heart beat very fast and my cheeks felt warm. Before Mrs. Darvish could see my eyes getting teary, I looked down and slowly unzipped my schoolbag. I found my notebook and opened it to the first page. I reached in again, took out my pencil box, and chose the one with the pointiest tip.

Satisfied, Mrs. Darvish clapped her hands a few times and said, “All right, class. Keep practicing!”

She returned to her desk in the front of the room, where she stood and rifled through some papers. Anahita slipped her hand under her desk and reached for mine, giving it a firm squeeze.

I looked at her and she smiled.

Anahita was about to whisper something, but we heard Mrs. Darvish scraping her chair and sitting down. We let go of each other’s hands. Mrs. Darvish looked around the classroom to make sure all students were working. I grabbed my pencil and pretended to be writing just as diligently as everyone else.