По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

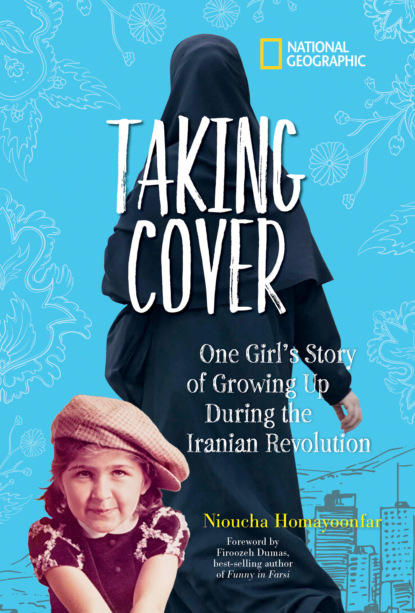

Taking Cover: One Girl's Story of Growing Up During the Iranian Revolution

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A few months before, I had heard her say to another teacher, “Let’s organize a play to keep the kids distracted from everything that’s happening.” I vaguely remembered Mrs. Ganji asking for volunteers to perform in a tale from The Arabian Nights. Most of the class had raised their hands high, nearly falling over their benches. Anahita had not, so even though I wanted to be in it, I didn’t volunteer either. I didn’t want her to feel left out. Later she told me she felt too shy to stand in front of a crowd, even if our performance was only going to be for students and a few teachers.

Now I understood her reluctance. In fact, I felt terrified to have been chosen. I tried to back out, but when Mrs. Ganji said I had no lines to memorize, I agreed to do it. My part as the king’s brother was to sit next to him and eat what the servants presented on trays.

That seemed simple enough, and I did well during rehearsal just sitting there on my chair and pretending to eat invisible cookies. The following day after our lunch break, the entire elementary school filed into the auditorium for our performance. I was all dressed up in a green velvet robe and sat proudly onstage. At one point in the play, a servant brought a platter of raisin cookies and I ate two, careful not to get any crumbs on my fancy outfit. During the rehearsal, the tray had been empty, so this was a nice surprise. Before I knew it, the play ended with tremendous applause from the packed auditorium. I felt a little embarrassed to bow my thanks along with all my classmates because I knew I hadn’t done anything to deserve such a warm reception.

Backstage, Mrs. Ganji greeted us with hugs and kisses. She then asked us to line up behind the curtain and get ready to return to the stage, introduce ourselves, and say what part we played.

I was the first to go, except I didn’t know what I was supposed to say. All this time I’d thought I had no lines, and now faced with this new piece of information, I stood completely frozen. Mrs. Ganji must have noticed the panic in my eyes because she took my hand and said, “Nioucha, don’t be scared. Just go out there, say your name, and the role you played.”

“And how do I do that?”

“Well, you take the microphone and say ‘Nioucha H. in the role of the prince.’“

I couldn’t feel my tongue. My ears were warm and made strange noises. I walked onstage and stared out into the crowd as I held the microphone to my mouth. My heart was pounding furiously. I couldn’t remember what I had to say. I looked back to Mrs. Ganji for help, but she only motioned for me to hurry up.

“Hi! I am the prince playing the role of Nioucha H.”

With all the buzzing in my ears, I barely heard my own voice. I glanced over at Mrs. Ganji, pleased to have gotten words out of my mouth. When I looked back at the audience to bow, I saw that everyone was laughing. Anahita covered her mouth to hide the fact that she wanted to laugh too.

She winked, waved with her other hand, and shrugged as if to say, “It’s no big deal.”

Mrs. Ganji came out, took the microphone from me, and looking very amused, whispered, “It’s all right, Nioucha. At least everyone will remember you now.”

I returned backstage and hid in the dressing room until it was time to go home. When I thought most of the school had emptied, I ran out to meet Baba, who was picking me up. Baba asked about the play, but I refused to answer him at first, not wanting to relive the shameful experience. But then he gave me his coaxing look and his wink, and I relented. When I finished, I glanced over and caught him smiling.

“It’s not funny, Baba,” I said a little too loudly. “Everyone was laughing at me!”

“It’s a little funny.”

He reached across the gearshift and gently pinched my cheek.

“Try to see the humor in it and laugh along with your friends.”

I couldn’t let my embarrassment go. And then I felt worse than embarrassed. I felt ashamed that I’d been so caught up in the play that I’d forgotten about Bianca and her father.

“Baba, I have something to tell you.”

I told him what Keyvan had said. Baba drove quietly for so long that I finally asked, “Did you hear me?”

“I did. I’m sorry about your friend and her father.”

His lips were very thin, like they got when he was angry or concentrating on something. His hands gripped the wheel hard, turning his knuckles white. I didn’t know what to say or do, so I slouched inside my collar and closed my eyes. I soon realized we weren’t on our way home.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“To Minoo’s.”

When we reached my aunt’s house, Baba rushed up the driveway. I followed him inside. After exchanging greetings, he leaned into his sister’s ear and whispered something. She turned pale and slapped her cheek with her hand in despair. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen her or other Iranians do this, but it still took me by surprise that someone would actually hit their own face to show how shocked they were about something. Aunt Minoo’s legs seemed to sway under her, so Baba held her arm. They walked briskly into the library, closing the door behind them.

I stood awhile in the entrance of Aunt Minoo’s house, waiting for them to come out. But they didn’t. Eventually, I walked into the kitchen and looked around the room. This house was so familiar to me, it felt like my second home. Minoo was only two years younger than Baba, and they had been very close growing up. When we had moved to Iran from the United States, we lived with Minoo and her family for almost six months before finding our own apartment.

—

That first night in Tehran, Aunt Minoo’s house had looked like a castle I might have seen in a cartoon. With all the lights on and situated on top of a hill, her home glowed in the dark almost like a Halloween jack-o’-lantern. There was a beautiful smell in the air, one I had not known before. Two large jasmine bushes stood on either side of the entrance, filling the evening with their magical perfume.

Aunt Minoo had given us a tour of their new two-story house. She was so excited to show it to us. Every room had bright colors. The living room and dining room were decorated in white curtains and Persian rugs, with tall windows all around. The kitchen had maroon tiles and white cabinets. Large wooden bookcases lined the library walls, and an inviting brown leather sofa waited for anyone who wanted to sit and sample any of the books. Upstairs, my cousin Sara’s room was all pink, my cousin Omid’s room was brown and orange, my aunt and uncle’s room was all white, the guest bedroom was orange, and the TV room was beige. I felt like I’d walked into a rainbow.

When Aunt Minoo spoke, it sounded like she was laughing. She was petite, but her big smile looked like Baba’s. I had overheard Baba say to Maman how happy he was that his sister had married well, affording her luxuries the rest of the family did not have. He said she was the most generous person he knew and that she loved to share her wealth with those around her.

Sara took after her mother in her generosity and kind spirit. Already 14 when we arrived, she shared her bedroom with me, her five-year-old cousin.

She had arranged her collection of stuffed animals neatly on her dresser—a dozen cats, five puppies, and three frogs. I really liked the frogs. I’d never seen any at the toy store Maman used to take me to in Pittsburgh. I had been surprised to see that a teenager still had toys in her room, but I had instantly loved her for it.

Despite feeling comfortable with my cousin, I felt scared in Aunt Minoo’s big house.

One morning, just a few weeks after we came to Iran, Maman had pulled the pink curtains aside in Sara’s room to let the sun in. Maman wore a short-sleeved navy dress with a red belt, and a wide red headband held back her long blond hair. She looked normal to me, but something about the house felt far from normal.

“Good morning, chérie.”

“Good morning, Maman. Can you come to the bathroom with me?”

“Are you still frightened?” Maman asked. “Maman, there’s a ghost living outside that bathroom window. I just know it.”

“All you’re hearing is the ivy from the neighbor’s house rustling in the breeze.”

“No, Maman, I’ve heard the ghost walking. It is really scary.”

“I’m sure it’s just the neighbor’s cat walking on the gravel downstairs. You’ve seen that cat. He’s adorable.”

“It’s not the cat.”

“All right, Nioucha. It’s time for me to go now.”

“Are you leaving already?”

Maman had started working for a French oil company as an executive secretary.

“Yes, I’m leaving soon,” she said, kissing the top of my head.

I wrapped my arms around her waist, wishing she could stay longer, at least through breakfast.

“Can’t you take me to school today?” I asked.

“I’m sorry, chérie, but I can’t.”

This was the first job Maman had taken since I was born, and I couldn’t stand not having her all to myself anymore.

When I wouldn’t let go, she added, “I’ll be here when you get back from school. I have to go now. Baba will take you.”