По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

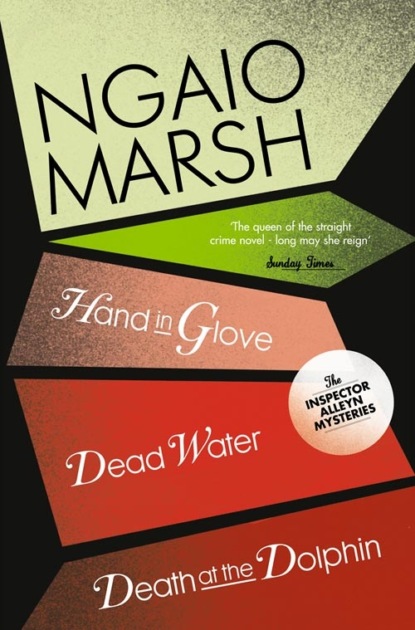

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 8: Death at the Dolphin, Hand in Glove, Dead Water

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Nicola looked squarely at Alleyn. ‘It couldn’t matter less,’ she said, ‘but I would like to mention that I did not have a casual affair with Andrew. We talked – and talked –’

Her voice faded on an indeterminate note. She was back at the end of Mr Period’s lane, in Andrew’s draughty car, tucked up in Andrew’s old duffel coat that smelt of paint. The tips of their cigarettes glowed and waned. Every now and then a treasure-hunter’s car would go hooting past and they would see the occupants get out and poke about the drain-pipes and heaps of soil, flicking their torches and giggling. And Andrew talked – and didn’t initiate any of the usual driver’s seat techniques but was nevertheless very close to her. And the moon had gone down and the stars were bright and everything in the world seemed brand new and shining. She gave Alleyn the factual details of this experience.

‘Do you remember,’ he asked, ‘how many cars stopped by the drain or who any of the people were?’

‘Not really. They were all new to me: lots of Nigels and Michaels and Sarahs and Davids and Gileses.’

‘You could see them fairly clearly?’

‘Fairly. There was a hurricane lantern shining on two planks across the ditch and they all had torches.’

‘Any of them walk across the planks?’

‘I think most of them. But the clue was under one of the drain-pipes on the road side of the ditch. We’d see them find it and giggle over it and put it back and then go zooming off.’

‘Anyone touch the planks? Look under the ends for the clue?’

‘I don’t think so.’ Nicola hesitated and then said: ‘I remember Leonard and Moppett. They were the last and they hadn’t got a torch. He crossed the planks and stooped over as if he was looking in the ditch. I got the impression that they stared at us. There was something, I don’t know what, kind of furtive about him. I can see him now,’ Nicola said, surprised at the vivid memory. ‘I think he had his hand inside his overcoat. The lamplight was on him. He turned his back to us. He stooped and straightened up. Then he recrossed the bridge and found the clue. They looked at it by the light of the lantern and he put it back and they drove away.’

‘Was he wearing gloves?’

‘Yes, he was. Light-coloured ones. Tight-fitting wash-leather I should think: a bit too svelte like everything else about Leonard.’

‘Anything more?’

‘No. At least – well, they didn’t sort of talk and laugh like the others. I don’t suppose any of this matters.’

‘Don’t you, indeed? And then, you good, observant child?’

‘Well, Andrew said: “Funny how ghastly they look even at this distance!” And I said: “Like – !” No, it doesn’t matter.’

‘Like what?’

‘“Like grand-opera assassins” was what I said but it was a silly remark. Actually, they looked more like sneak thieves but I can’t tell you why. It’s nothing.’

‘And then?’

‘Well, they were the last couple. You see, Andrew kept count, vaguely, because he thought it would be all right to continue our conversation as long as there were still hunters to come. But before them, Lady Bantling and Mr Period came past. She was driving him home. She stopped the car by the planks and I fancy she called out to a hunting couple that were just leaving. Mr Period got out and said good night with his hat off, looking rather touching, poor sweet, and crossed the planks and went in by his side gate. And she turned the car.’ Nicola stopped.

‘What is it?’

‘Well, you see, I – I don’t want –’

‘All right. Don’t bother to tell me. You’re afraid of putting ideas into my head. How can I persuade you, Nicola, that it’s only by a process of elimination that I can get anywhere with this case? Incidents that look as fishy as hell to you may well turn out to be the means of clearing the very character you’re fussing about.’

‘May they?’

‘Now, look here. An old boy of, as far as we know, exemplary character, has been brutally and cunningly murdered. You think you can’t bring yourself to say anything that might lead to an arrest and its possible consequences. I understand and sympathize. But, my poor girl, will you consider for a moment, the possible consequences of withholding information? They can be disastrous. They have led to terrible miscarriages of justice. You see, Nicola, the beastly truth is that if you are involved, however accidentally in a crime of this sort, you can’t avoid responsibility.’

‘I’m sorry. I suppose you’re right. But in this instance – about Lady Bantling, I mean – it’s nothing. It’ll sound disproportionate.’

‘So will lots of other things that turn out to be of no consequence. Come on. What happened? What did she do?’

Nicola, it transpired, had a gift for reportage. She gave a clear account of what had happened … Alleyn could see the car turn in the lane and stop. After a pause the driver got out, her flaming hair haloed momentarily in the light of the lantern as she crossed the planks, walking carefully in her high heels. She had gone through Mr Period’s garden gate and disappeared. There had been a light in an upper window. Andrew Bantling had said: ‘Hallo, what’s my incalculable ma up to!’ They had heard quite distinctly the spatter of pebbles against the upper window. A figure in a dark gown had opened it. ‘Great grief!’ Andrew had ejaculated. ‘That’s Harold! She’s doing a balcony scene in reverse! She must be tight.’

And indeed, Lady Bantling had, surprisingly, quoted from the play. ‘“What light,” she had shouted, “from yonder window breaks?”’ and Mr Cartell had replied irritably, ‘Good God, Desirée, what are you doing down there!’

Her next remark was in a lower tone and they had only caught the word ‘warpath’ to which he had rejoined: ‘Utter nonsense!’

‘And then,’ Nicola told Alleyn, ‘another light popped up and another window opened and Mr Period looked out. It was like a Punch and Judy show. He said something rather plaintive that sounded like: “Is anything the matter?” and Lady Bantling shouted: “Not a thing, go to bed, darling,” and he said: “Well, really! How odd!” and pulled down his blind. And then Mr Cartell said something inaudible and Lady Bantling quite yelled: “Ha! Ha! You jolly well watch your step,” and then he pulled his blind down and we saw her come out, cross the ditch, and get into the car. She drove past us and leant out of the driving window and said: “That was a tuppenny one. Don’t be too late, darlings” and went on. And Andrew said he wished he knew what the hell she was up to and soon after that we went back to the party. Leonard and Moppett had already arrived.’

‘Was Desirée Bantling, in fact, tight?’

‘It’s hard to say. She was perfectly in order afterwards and acted with the greatest expediency, I must say, in the Pixie affair. She’s obviously,’ Nicola said, ‘a law unto herself.’

‘I believe you. You’ve drifted into rather exotic and dubious waters, haven’t you?’

‘It was all right,’ Nicola said quickly. ‘And Andrew’s not a bit exotic or dubious. He’s a quiet character. Honestly. You’ll see.’

‘Yes,’ Alleyn said. ‘I’ll see. Thank you, Nicola.’ Upon which the door of Mr Period’s drawing-room burst open and Andrew, scarlet in the face, stormed in.

‘Look here!’ he shouted, ‘what the hell goes on? Are you grilling my girl?’

IV

Alleyn, with one eyebrow cocked at Nicola, was crisp with Andrew. Nicola herself, struggling between exasperation and a maddening tendency to giggle invited Andrew not to be an ass and he calmed down and presently apologized.

‘I’m inclined to be quick-tempered,’ he said with an air of self-discovery and an anxious glance at Nicola.

She cast her eyes up and, on Alleyn’s suggestion, left Andrew with him and went to the study. There she found Mr Period in a dreadful state of perturbation, writing a letter.

‘About poor old Hal,’ he explained distractedly. ‘To his partner. One scarcely knows what to say.’

He implored Nicola to stay and as she still had a mass of unassembled notes to attend to, she set to work on them in a strange condition of emotional uncertainty.

Alleyn had little difficulty with Andrew Bantling. He readily outlined his own problems, telling Alleyn about the Grantham Gallery and how Mr Cartell had refused to let him anticipate his inheritance. He also confirmed Nicola’s account of their vigil in the car. ‘You don’t,’ he said, ‘want to take any notice of my mamma. She was probably a thought high. It would amuse her to bait Harold. She always does that sort of thing.’

‘She was annoyed with him, I take it?’

‘Well, of course she was. Livid. We both were.’

‘Mr Bantling,’ Alleyn said, ‘your step-father has been murdered.’

‘So I feared,’ Andrew rejoined. ‘Beastly, isn’t it? I can’t get used to the idea at all.’

‘A trap was laid for him and when, literally, he fell into it, his murderer levered an eight-hundred-pound drain-pipe on him. It crushed his skull and drove him, face down, into the mud.’

The colour drained out of Andrew’s cheeks. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘You needn’t go on. It’s loathsome. It’s too grotesque to think about.’