По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

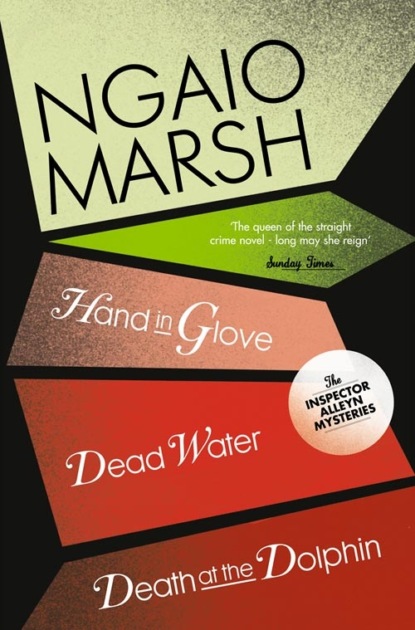

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 8: Death at the Dolphin, Hand in Glove, Dead Water

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Was there some talk of Mr Leiss buying a car?’

She bent over the dog. ‘That’s enough,’ she said to it. ‘You’ve had enough.’ And then to Alleyn: ‘It all petered out. He didn’t buy it.’

The door opened and her Austrian maid came in with a letter.

‘From Mr Period, please,’ she said. ‘The man left it.’

Miss Cartell seemed unwilling to take the letter. The maid put it on the desk at her elbow.

‘All right, Trudi,’ Miss Cartell mumbled. ‘Thank you,’ and the maid went out.

‘Pay no attention to me,’ Alleyn said.

‘It’ll wait.’

‘Don’t you think, perhaps, you should look at it?’

She opened the letter unhandily and as she read it turned white to the lips.

‘What is it?’ he asked, ‘Miss Cartell, what’s the matter?’

The letter was still quivering in her hands.

‘He must be mad,’ she said. ‘Mad!’

‘May I see it?’

She seemed to consider this but in an aimless sort of way as if she only gave him half her attention. When he took the sheet of paper from her fingers she suffered him to do so as if they were inanimate.

Alleyn read the letter.

‘My dear: What can I say? Only that you have lost a devoted brother and I a very dear friend. I know so well, believe me so very well, what a shock this has been for you and how bravely you will have taken it. If it is not an impertinence in an old friend to do so, may I offer you these few simple lines written by my dear and so Victorian Duchess of Rampton? They are none the worse, I hope, for their unblushing sentimentality.

So it must be, dear heart, I’ll not repine

For while I live the Memory is Mine.

I should like to think that we know each other well enough for you to believe me when I say that I hope you won’t dream of answering this all-too-inadequate attempt to tell you how sorry I am.

Yours sincerely,

Percival Pyke Period

Alleyn folded the paper and looked at Miss Cartell. ‘But why,’ he said, ‘do you say that? Why do you say he must be mad?’

She waited so long, gaping at him like a fish, that he thought she would never answer. Then she made a fumbling, inelegant gesture towards the letter.

‘Because he must be,’ she said. ‘Because it’s all happening twice. Because he’s written it before. The lot. Just the same.’

‘You mean –? But when?’

‘This morning,’ Connie said and began rootling in the litter on her desk. ‘Before breakfast. Before I knew.’

She drew in her breath with a whistling noise. ‘Before anybody knew,’ she said. ‘Before they had found him.’

She stared at Alleyn, nodding her head and holding out a sheet of letter-paper.

‘See for yourself,’ she said miserably. ‘Before they had found him.’

Alleyn looked at the two letters. Except in one small detail they were, indeed, exactly the same.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_2bdd3247-6740-5633-96e4-7066f5f2370c)

Postscript to a Party (#ulink_2bdd3247-6740-5633-96e4-7066f5f2370c)

Connie raised no objections to his keeping the letters and with them both in his pocket he asked if he might see Miss Ralston and Mr Leiss. She said that they were still asleep in their rooms and added, with a slight hint of gratification, that they had attended the Baynesholme festivities.

‘One of Desirée Bantling’s dotty parties,’ she said. ‘They go on till all hours. Moppett left a note asking not to be roused.’

‘It’s now one o’clock,’ Alleyn said, ‘and I’m afraid I shall have to disturb Mr Leiss.’

He thought she was going to protest but at that moment the Pekinese set up a petulant demonstration, scratching at the door and raising a crescendo of imperative yaps.

‘Clever boy!’ Connie said distractedly. ‘I’m coming!’ She went to the door. ‘I’ll have to see to this,’ she said. ‘In the garden.’

‘Of course,’ Alleyn agreed. He followed them into the hall and saw them out through the front door. Once in the garden the Pekinese bolted for a newly raked flowerbed.

‘Oh, no!’ Connie ejaculated. ‘After lunch,’ she shouted as she hastened in pursuit of her pet. ‘Come back later.’

The Pekinese tore round a corner of the house and she followed it.

Alleyn re-entered the house and went quickly upstairs.

On the landing he encountered Trudi, the maid, who showed him the visitors’ rooms. They were on two sides of a passage.

‘Mr Leiss?’ Alleyn asked.

A glint of feminine awareness momentarily transfigured Trudi’s not very expressive face.

‘He is sleeping,’ she said. ‘I looked at him. He sleeps like a god.’

‘We’ll see what he wakes like,’ Alleyn said, tipping her rather handsomely. ‘Thank you, Trudi.’

He tapped smartly on the door and went in.

The room was masked from its entrance by an old-fashioned scrap screen. Behind this a languid, indefinably Cockney voice said: ‘Come in.’

Mr Leiss was awake but Alleyn thought he saw what Trudi meant: the general effect was in Technicolor. The violet silk pyjama jacket was open, the torso was bronzed, smooth and rather shiny as well as hirsute. A platinum chain lay on the chest. The glistening hair was slightly disarranged and the large brown eyes were open. When they lighted on Alleyn they narrowed. There was a slight convulsive movement under the bedclothes. The room smelt dreadfully of some indefinable unguent.