По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

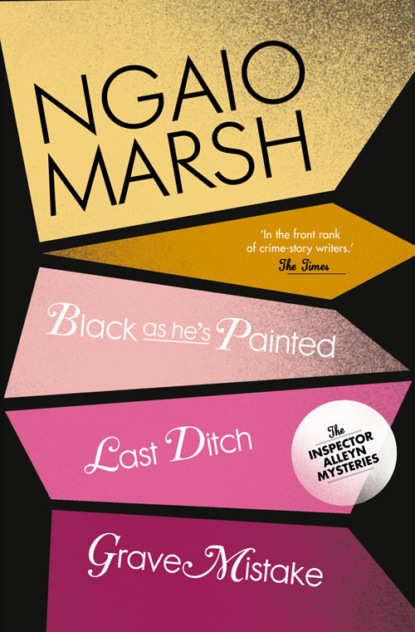

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He wrote cosily to his married sister in Devonshire: ‘– you may be surprised to hear of the change. Don’t expect anything spectacular, it’s a quiet little backwater full of old fogies like me. Nothing in the way of excitement or “happenings” or violence or beastly demonstrations. It suits me. At my age one prefers the uneventful life and that,’ he ended, ‘is what I expect to enjoy at No. 1, Capricorn Walk.’

Prophecy was not Mr Whipplestone’s strong point.

III

‘That’s all jolly fine,’ said Superintendent Alleyn. ‘What’s the Special Branch think it’s doing? Sitting on its fat bottom waving Ng’ombwanan flags?’

‘What did he say, exactly?’ asked Mr Fox. He referred to their Assistant Commissioner.

‘Oh, you know!’ said Alleyn. ‘Charm and sweet reason were the wastewords of his ween.’

‘What’s a ween, Mr Alleyn?’

‘I’ve not the remotest idea. It’s a quotation. And don’t ask me from where.’

‘I only wondered,’ said Mr Fox mildly.

‘I don’t even know,’ Alleyn continued moodily, ‘how it’s spelt. Or what it means, if it comes to that.’

‘If it’s Scotch it’ll be with an h, won’t it? Meaning: “few”. Wheen.’

‘Which doesn’t make sense. Or does it? Perhaps it should be “weird” but that’s something one drees. Now you’re upsetting me, Br’er Fox.’

‘To get back to the AC, then?’

‘However reluctantly: to get back to him. It’s all about this visit, of course.’

‘The Ng’ombwanan President?’

‘He. The thing is, Br’er Fox, I know him. And the AC knows I know him. We were at school together in the same house: Davidson’s. Same study, for a year. Nice creature, he was. Not everybody’s cup of tea but I liked him. We got on like houses on fire.’

‘Don’t tell me,’ said Fox. ‘The AC wants you to recall old times?’

‘I do tell you precisely that. He’s dreamed up the idea of a meeting – casual-cum-official. He wants me to put it to the President that unless he conforms to whatever procedure the Special Branch sees fit to lay on, he may very well get himself bumped off and in any case will cause acute anxiety, embarrassment and trouble at all levels from the Monarch down. And I’m to put this, if you please, tactfully. They don’t want umbrage to be taken, followed by a highly publicized flounce-out. He’s as touchy as a sea-anemone.’

‘Is he jibbing, then? About routine precautions?’

‘He was always a pig-headed ass. We used to say that if you wanted the old Boomer to do anything you only had to tell him not to. And he’s one of those sickening people without fear. And hellish haughty with it. Yes, he’s jibbing. He doesn’t want protection. He wants to do a Haroun el Raschid and bum round London on his own looking as inconspicuous as a coal box in paradise.’

‘Well,’ said Mr Fox judiciously, ‘that’s a very silly way to go on. He’s a number one assassination risk, that gentleman.’

‘He’s a bloody nuisance. You’re right, of course. Ever since he pushed his new industrial legislation through he’s been a sitting target for the lunatic fringe. Damn it all, Br’er Fox, only the other day, when he elected to make a highly publicized call at Martinique, somebody took a pot shot at him. Missed and shot himself. No arrest. And off goes the Boomer on his merry way, six foot five of him, standing on the seat of his car, all eyes and teeth, with his escort having kittens every inch of the route.’

‘He sounds a right daisy.’

‘I believe you.’

‘I get muddled,’ Mr Fox confessed, ‘over these emergent nations.’

‘You’re not alone, there.’

‘I mean to say – this Ng’ombwana. What is it? A republic, obviously, but is it a member of the Commonwealth and if it is, why does it have an Ambassador instead of a High Commissioner?’

‘You may well ask. Largely through the manoeuvrings of my old chum, The Boomer. They’re still a Commonwealth country. More or less. They’re having it both ways. All the trappings and complete independence. All the ha’pence and none of the kicks. That’s why they insist on calling their man in London an Ambassador and setting him up in premises that wouldn’t disgrace one of the great powers. Basically it’s The Boomer’s doing.’

‘What about his own people? Here? At this Embassy? His Ambassador and all?’

‘They’re as worried as hell but say that what the President lays down is it: the general idea being that they might as well speak to the wind. He’s got this notion in his head – it derives from his schooldays and his practising as a barrister in London – that because Great Britain, relatively, has had a non-history of political assassination there won’t be any in the present or future. In its maddening way it’s rather touching.’

‘He can’t stop the SB doing its stuff, though. Not outside the Embassy.’

‘He can make it hellish awkward for them.’

‘What’s the procedure, then? Do you wait till he comes, Mr Alleyn, and plead with him at the airport?’

‘I do not. I fly to his blasted republic at the crack of dawn tomorrow and you carry on with the Dagenham job on your own.’

‘Thanks very much. What a treat,’ said Fox. ‘So I’d better go and pack.’

‘Don’t forget the old school tie.’

‘I do not deign,’ said Alleyn, ‘to reply to that silly crack.’

He got as far as the door and stopped.

‘I meant to ask you,’ he said. ‘Did you ever come across a man called Samuel Whipplestone? At the FO?’

‘I don’t move in those circles. Why?’

‘He was a bit of a specialist on Ng’ombwana. I see he’s lately retired. Nice chap. When I get back I might ask him to dinner.’

‘Are you wondering if he’d have any influence?’

‘We can hardly expect him to crash down on his knees and plead with the old Boomer to use his loaf if he wants to keep it. But I did vaguely wonder. ‘Bye, Br’er Fox.’

Forty-eight hours later Alleyn, in a tropical suit, got out of a Presidential Rolls that had met him at the main Ng’ombwana airport. He passed in a sweltering heat up a grandiose flight of steps through a Ruritanian guard turned black, and into the air-conditioned reception hall of the Presidential Palace.

Communication at the top level had taken place and he got the full, instant VIP treatment.

‘Mr Alleyn?’ said a young Ng’ombwanan wearing an ADC’s gold knot and tassel. ‘The President is so happy at your visit. He will see you at once. You had a pleasant flight?’

Alleyn followed the sky-blue tunic down a splendid corridor that gave on an exotic garden.

‘Tell me,’ he asked on the way, ‘what form of address is the correct one for the President?’

‘His Excellency, the President,’ the ADC rolled out, ‘prefers that form of address.’

‘Thank you,’ said Alleyn, and followed his guide into an anteroom of impressive proportions. An extremely personable and widely smiling secretary said something in Ng’ombwanan. The ADC translated: ‘We are to go straight in, if you please.’ Two dashingly uniformed guards opened double-doors and Alleyn was ushered into an enormous room at the far end of which, behind a vast desk, sat his old school chum: Bartholomew Opala.