По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

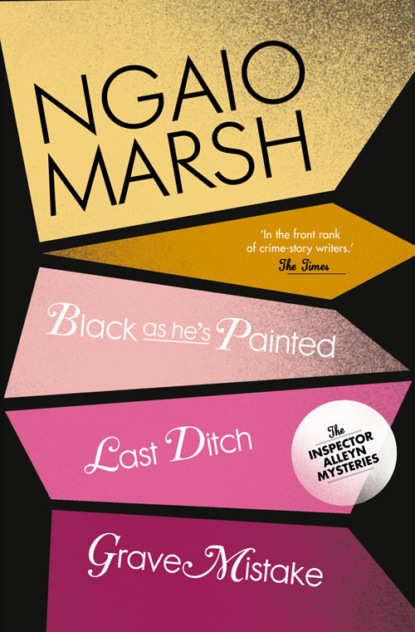

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Superintendent Alleyn, your Excellency, Mr President, sir,’ said the ADC redundantly and withdrew.

The enormous presence was already on its feet and coming, light-footed as a prizefighter, at Alleyn. The huge voice was bellowing: ‘Rory Alleyn, but all that’s glorious!’ Alleyn’s hand was engulfed and his shoulder-blade rhythmically beaten. It was impossible to stand to attention and bow from the neck in what he had supposed to be the required form.

‘Mr President –’ he began.

‘What? Oh, nonsense, nonsense, nonsense! Balls, my dear man (as we used to say in Davidson’s).’ Davidson’s had been their house at the illustrious school they both attended. The Boomer was being too establishment for words. Alleyn noticed that he wore the old school tie and that behind him on the wall hung a framed photograph of Davidson’s with The Boomer and himself standing together in the back row. He found this oddly, even painfully, touching.

‘Come and sit down,’ The Boomer fussed. ‘Where, now? Over here! Sit! Sit! I couldn’t be more delighted.’

The steel-wool mat of hair was grey now and stood up high on his head like a toque. The huge frame was richly endowed with flesh and the eyes were very slightly bloodshot but, as if in double-exposure, Alleyn saw beyond this figure that of an ebony youth eating anchovy toast by a coal fire and saying: ‘You are my friend: I have had none, here, until now.’

‘How well you look,’ the President was saying. ‘And how little you have changed! You smoke? No? A cigar? A pipe? Yes? Presently, then. You are lunching with us of course. They have told you?’

‘This is overwhelming,’ Alleyn said when he could get a word in. ‘In a minute I shall be forgetting my protocol.’

‘Now! Forget it now. We are alone. There is no need.’

‘My dear –’

‘“Boomer.” Say it. How many years since I heard it!’

‘I’m afraid I very nearly said it when I came in. My dear Boomer.’

The sudden brilliance of a prodigal smile made its old impression. ‘That’s nice,’ said the President quietly and after rather a long silence: ‘I suppose I must ask you if this is a visit with an object. They were very non-committal at your end, you know. Just a message that you were arriving and would like to see me. Of course I was overjoyed.’

Alleyn thought: this is going to be tricky. One word in the wrong place and I not only boob my mission but very likely destroy a friendship and even set up a politically damaging mistrust. He said –

‘I’ve come to ask you for something and I wish I hadn’t got to bother you with it. I won’t pretend that my chief didn’t know of our past friendship – to me a most valued one. I won’t pretend that he didn’t imagine this friendship might have some influence. Of course he did. But it’s because I think his request is reasonable and because I am very greatly concerned for your safety, that I didn’t jib at coming.’

He had to wait a long time for the reaction. It was as if a blind had been pulled down. For the first time, seeing the slackened jaw and now the hooded, lacklustre eyes he thought, specifically: ‘I am speaking to a Negro.’

‘Ah!’ said the President at last, ‘I had forgotten. You are a policeman.’

‘They say, don’t they, if you want to keep a friend, never lend him money. I don’t believe a word of it, but if you change the last four words into “never use your friendship to further your business” I wouldn’t quarrel with it. But I’m not doing exactly that. This is more complicated. My end object, believe it or not, sir, is the preservation of your most valuable life.’

Another hazardous wait. Alleyn thought: ‘Yes, and that’s exactly how you used to look when you thought somebody had been rude to you. Glazed.’

But the glaze melted and The Boomer’s nicest look – one of quiet amusement – supervened.

‘Now, I understand,’ he said. ‘It is your watch-dogs, your Special Branch. “Please make him see reason, this black man. Please ask him to let us disguise ourselves as waiters and pressmen and men-in-the-street and unimportant guests and be indistinguishable all over the shop.” I am right? That is the big request?’

‘I’m afraid, you know, they’ll do their thing in that respect, as well as they can, however difficult it’s made for them.’

‘Then why all this fuss-pottery? How stupid!’

‘They would all be much happier if you didn’t do what you did, for instance, in Martinique.’

‘And what did I do in Martinique?’

‘With the deepest respect: insisted on an extensive reduction of the safety precautions and escaped assassination by the skin of your teeth.’

‘I am a fatalist,’ The Boomer suddenly announced, and when Alleyn didn’t answer: ‘My dear Rory, I see I must make myself understood. Myself. What I am. My philosophy. My code. You will listen?’

‘Here we go,’ Alleyn thought. ‘He’s changed less than one would have thought possible.’ And with profound misgivings he said: ‘But of course, sir. With all my ears.’

As the exposition got under way it turned out to be an extension of The Boomer’s schoolboy bloody-mindedness seasoned with, and in part justified by, his undoubted genius for winning the trust and understanding of his own people. He enlarged, with intermittent gusts of Homeric laughter, upon the machinations of the Ng’ombwanan extreme right and left who had upon several occasions made determined efforts to secure his death and were, through some mysterious process of reason, thwarted by The Boomer’s practice of exposing himself as an easy target. ‘They see,’ he explained, ‘that I am not (as we used to say at Davidson’s) standing for their tedious codswallop.’

‘Did we say that at Davidson’s?’

‘Of course. You must remember. Constantly.’

‘So be it.’

‘It was a favourite expression of your own. Yes,’ shouted The Boomer as Alleyn seemed inclined to demur, ‘always. We all picked it up from you.’

‘To return, if we may, to the matter in hand.’

‘All of us,’ The Boomer continued nostalgically. ‘You set the tone (at Davidson’s),’ and noticing perhaps a fleeting expression of horror on Alleyn’s face, he leant forward and patted his knees. ‘But I digress,’ he said accurately, ‘Shall we return to our muttons?’

‘Yes,’ Alleyn agreed with heartfelt relief. ‘Yes. Let’s.’

‘Your turn,’ The Boomer generously conceded. ‘You were saying?’

‘Have you thought – but of course you have – what would follow if you were knocked off?’

‘As you say: of course I have. To quote your favourite dramatist (you see, I remember), “the filthy clouds of heady murder, spoil and villainy” would follow,’ said The Boomer with relish. ‘To say the least of it,’ he added.

‘Yes. Well now: the threat doesn’t lie, as the Martinique show must have told you, solely within the boundaries of Ng’ombwana. In the Special Branch they know, and I mean they really do know, that there are lunatic fringes in London ready to go to all lengths. Some of them are composed of hangovers from certain disreputable backwaters of colonialism, others have a devouring hatred of your colour. Occasionally they are people with a real and bitter grievance that has grown monstrous in stagnation. You name it. But they’re there, in considerable numbers, organized and ready to go.’

‘I am not alarmed,’ said The Boomer with maddening complacency. ‘No, but I mean it. In all truth I do not experience the least sensation of physical fear.’

‘I don’t share your sense of immunity,’ Alleyn said. ‘In your boots I’d be in a muck sweat.’ It occurred to him that he had indeed abandoned the slightest nod in the direction of protocol. ‘But, all right. Accepting your fearlessness, may we return to the disastrous effect your death would have upon your country? “The filthy clouds of heady murder” bit. Doesn’t that thought at all predispose you to precaution?’

‘But, my dear fellow, you don’t understand. I shall not be killed. I know it. Within myself, I know it. Assassination is not my destiny: it is as simple as that.’

Alleyn opened his mouth and shut it again.

‘As simple as that,’ The Boomer repeated. He opened his arms. ‘You see!’ he cried triumphantly.

‘Do you mean,’ Alleyn said very carefully, ‘that the bullet in Martinique and the spear in a remote village in Ng’ombwana and the one or two other pot-shots that have been loosed off at you from time to time were all predestined to miss?’

‘Not only do I believe it but my people – my people – know it in their souls. It is one of the reasons why I am reelected unanimously to lead my country.’

Alleyn did not ask if it was also one of his reasons why nobody, so far, had had the temerity to oppose him.

The Boomer reached out his great shapely hand and laid it on Alleyn’s knee. ‘You were and you are my good friend,’ he said. ‘We were close at Davidson’s. We remained close while I read my law and ate my dinners at the Temple. And we are close still. But this thing we discuss now belongs to my colour and my race. My blackness. Please, do not try to understand: try only, my dear Rory, to accept.’

To this large demand Alleyn could only reply: ‘It’s not as simple as that.’