По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

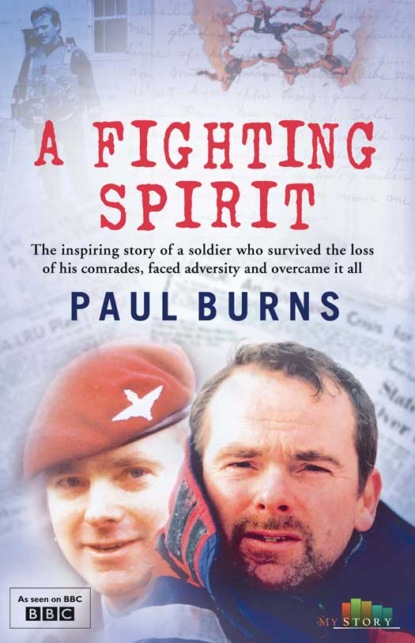

A Fighting Spirit

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Whenever I went back home to Nottingham, I felt that my eyes had been opened to a whole new way of life. A lot of the guys I had grown up with had simply moved from school into a dead-end job in the local pit or in some dreary factory. The biggest thing they had to talk about was that they were going out with a new girl, or had started drinking in a different pub. When they asked me what I’d been doing, I was able to say that I’d been potholing, or shooting, or climbing. I felt my life was fuller as a result of being a junior soldier, and it spurred me on. I may have been young, but I knew how I wanted things to pan out.

I wanted to progress to the full-blown Parachute Regiment. To don the red beret.

Chapter Two The Maroon Machine (#u3d276d15-a647-5f5c-aac5-fa77ede5856b)

At the age of 17 I moved on from the junior Paras and into 448 Platoon, Recruit Company, part of the training and assessment wing of the Parachute Regiment.

My time in Recruit Company would last six months, and right from day one I knew that I was embarking upon just about the most difficult training and selection regime that the regular British Army has to offer. The Parachute Regiment attracts all manner of men, so as well as others from all over the UK, I rubbed shoulders with Rhodesians and New Zealanders and even an Australian submariner who had decided he wanted a change of scene. New recruits are known as ‘Crows’, ‘Joe Crow’ being the personification of the new recruit. The youngsters who had come together in the Parachute Regiment Depot at Browning Barracks were there with the express intention of making the transition from a Crow to a Tom.

We were a pretty motley crew, even after those few guys who realized they’d made a big mistake had exercised their ‘discharge by right’, which meant they were allowed to leave within the first eight weeks on payment of a £100 fee. For a lot of young lads, it is their first time away from home. Going from a nice, cosy house where your mum makes your bed to having your hair shaved off and being under the watchful eye of one of Recruit Company’s training corporals—some of the regiment’s most respected and fearsome members—can be a bit of a shock to the system. No wonder that a fair few decide rather quickly that the Army is not for them.

But I was used to it, from my time as a junior soldier. In fact those of us who had already spent time at Aldershot were excused the first couple of weeks of training, during which new recruits were issued uniforms and taught the basics of Army life. The same went for my closest friends, two lads who had joined up as junior soldiers at the same time as me, and were now in the same section of Recruit Company. Their names were Ian Wood and Jeff Jones—Woody and Jonesy—and I also made friends with guys from other sections, like Taff Davies, Taff Elliott, and Graham Eve. Woody, Jonesy and I hit it off the moment we met. Like the rest of our intake, they were straightforward, friendly guys. Woody was a cheeky little chap, always smiling, always happy. The kind of lad who’s always fun to have around. Jonesy was the tallest guy in the Company. I was the second tallest, so when we were on parade we were always next to each other. The three of us were billeted together in the juniors, and thick as thieves in Recruit Company. There was an amazing camaraderie among us, I suppose because we all wanted the same thing—we were driven, professional and hungry to succeed, even though most of us were very young.

We were taught regimental history—about Churchill and the Parachute Regiment’s exploits during the Second World War and afterwards. It was important stuff, not because the training corporals wanted to turn out an intake of historians, but because they wanted to hammer home the Paras’ belief in their own excellence. I remember being taught the words of Field Marshal Montgomery:

What manner of men are these who wear the maroon beret?

They are, first, all volunteers, and are toughened by hard physical training. As a result, they have that infectious optimism and that offensive eagerness which come from physical well-being.

They have jumped from the air and, by doing so, have conquered fear.

Their duty lies in the van of battle: they are proud of their honour, and have never failed in any task.

They have the highest standards in all things, whether it be skill in battle or smartness in execution of all peacetime duties.

They have shown themselves to be as tenacious and determined in defence as they are courageous in attack.

They are, in fact, men apart.

Every man an emperor.

It was stirring stuff, and although it would be true to say that during the rigours of Recruit Company we didn’t feel entirely emperor-like, it was certainly inspiring to know that if we worked hard enough we could become part of this elite band.

Recruit Company’s aim was twofold: to train the wannabe Paras and get their skills and fitness up to scratch; and to weed out those recruits who weren’t fully suited to joining the regiment. As well as the intense training, we had tests at regular intervals. Anyone who failed to meet the grade at any of these levels would be ‘back-squadded’, or made to retake that part of the course with the group who had joined after them. It happened to a lot of the guys, who found themselves unable to progress, either through lack of fitness or through injury. As the six months wore on, our numbers began to dwindle. I worked hard, but I also had my fair share of luck because the training became increasingly physical and increasingly brutal. We were put through our paces like never before, but we also underwent mental challenges such as sleep deprivation in an attempt to weed out those recruits who weren’t mentally tough enough to progress. We were sent on forced marches—mile after mile with full kit and personal weapons, with the promise of a truck waiting over the next hill that never seemed to be there. It sounds harsh, but it was necessary. As a soldier, you never know what difficulties you’re going to find yourself up against. (This is even more true now than it was in the days when I joined up. In Afghanistan, our young soldiers have to live in one of the harshest environments in the world, and each time they step outside they know they are going to be shot at.) The Parachute Regiment has a reputation for being able to cope with any situation, of being harder than any other regiment. Our training was specially designed to make sure we lived up to that reputation.

The days seemed to fly by. We were up at 0700 hours, and stood down at 2000. If you weren’t training during that time, you were studying; if you weren’t studying you were trying to get some ‘scoff ’ down your throat in a desperate attempt to put back some of the calories you’d lost during your fitness exercises. And when the lights went out, you slept the sleep of the dead.

We were beasted. Not bullied—at no point during my career in the British Army do I remember anything remotely resembling bullying. Beasting is different. It’s a way of keeping you on your toes, of making sure that you’re at the peak of physical fitness. A beasting could happen any time. You might be grabbing a rare moment of relaxation in the block after a hard day’s wading through rivers with full pack and rifle, when you’d hear a scream from outside your room.

‘Corridor!’

Instantly you had to present yourself in the corridor, where an instructor would have that look on his face that you just knew meant something unpleasant was around the corner.

‘Position!’

This meant you had to lean back against the wall in a sitting position with your arms out straight in front of you, but there was nothing to support your legs. Your knees would tremble; the muscles in your legs would burn. And you had to maintain that position for as long as you were told. Why? No reason, other than to make sure you were up to it. When you were up for inspection, you had to have yourself and your locker absolutely spotless, your boots gleaming, the floor of the barrack block polished to perfection. No matter how flawless you made things, you could bet that your locker would be emptied out all over the floor, or your boots flung out of the window, and you’d have to start all over again. Our days became a constant flurry of runs—over assault courses or through water up to your waist—and press-ups. The fitter you got, the faster and longer you were expected to exercise. Make the slightest mistake in a drill and the shout would go up: ‘Down and give me ten!’

If you were the right kind of person for the Paras, these beastings would make you more determined that they weren’t going to break you. If you were the wrong kind of person, you’d up and leave. That was the whole point.

It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Lots of guys left, but the more that fell by the wayside, the more confidence it gave those of us who remained. It felt good to be the ones who were left. Of the seventy-odd members of our Recruit Company who started out, only about twenty made it through, including myself, Woody and Jonesy. And as our training progressed, the bond between the successful recruits grew strong. We lived together in four-man rooms, and that four-man unit was the basis of everything we did. The tougher things became, the more the connection between us developed. We were all going through the same thing, so we understood how our mates were feeling. As we were pushed really hard in our training, we played equally hard in what little free time we had. A lot of drinking went on—Aldershot became a pretty entertaining place on a Friday night when all the soldiers came out to play—but our downtime was in many ways as important as our training time, because it all helped to strengthen the bond between us.

Looking back, I can see why this was an essential part of the training process. In operational situations, it would be crucial that we were able to communicate effectively with each other, sometimes without speaking. Perhaps we would be on patrol in the jungle, creeping silently through the bush and having to communicate with just a glance or a nod of the head. Or perhaps we would be soldiering in a more urban environment, and it was no secret during Recruit Company that the successful candidates would most likely end up doing a stint in Northern Ireland.There it was vital that each member of a four-man unit constantly watched his mates’ backs, and that everyone had an instinctive understanding of when something was wrong and an innate trust that the others would do whatever was necessary to see him right. All this was built up by the training and selection process—by living together, training together, sharing the same room, going to the mess, and drinking together. Your relationship with your mates became like a relationship with a girl—you knew in your gut when something wasn’t right just by looking at them and reading the look on their face. In the Army you fight for Queen and Country, but in reality you’re fighting for your mates, for the guys standing next to you in the battlefield. Effective soldiers are the ones who want to do this.

So, as people left Recruit Company, through injury, or after deciding this wasn’t the life for them, or simply being unable to take the pace, those of us who remained grew closer. But we all knew we still had another hurdle to cross before the end of our training was in sight. This was Pegasus Company, or P Company—the pre-parachute selection course. If you pass P Company, you’ve qualified for your red beret. Then you can go on to do your parachute training and get your wings.

Nowadays P Company takes place at the Infantry Training Battalion in Catterick, North Yorkshire, but back then it was in Aldershot. It exists not only for the Paras, but for any soldier or officer who wishes to serve with the airborne forces. And although this is a pre-parachute selection course, it has nothing to do with parachuting. Nobody was interested in our head for heights or the strength of our ankles for landing. It wasn’t even much to do with military ability—the P Company team aren’t concerned with drill or fieldcraft. Instead, the course exists to assess the recruits’ endurance, persistence and courage under extreme stress, to see whether they are made of the right stuff to serve with the airborne forces. It was everything we’d been building up to.

P Company consists of eight tests taken over five consecutive days. For seven of these tests you are given a score, while one of them is a matter of a straight pass or fail. At the end of the week, if you’ve got enough points, you’re through. The trouble is, only the instructors know what the pass mark is. P Company one of the hardest recruitment tests in the British Army, and not for the faint-hearted.

Day one starts off with a steeplechase. For us this involved jumping off scaffolding poles into stinking water which we had to wade through before taking one of only two slippery, awkward exit points on the other side. If you don’t get to the water quickly enough, you have to wait your turn while the other recruits make their exit, before continuing the 1.3-kilometre obstacle course. And then, when you’ve finished, you have to do it again. The steeplechase is against the clock—you’re aiming to complete it in under nineteen minutes. For every thirty seconds you go over that, you lose a point. It’s a killer.

When you’ve finished the steeplechase, there’s barely any time to rest. Next up is the log race, for which we were divided into teams of eight. Each team had to carry a telegraph pole weighing 130 pounds over two miles of bumpy terrain, the idea being to simulate having to manoeuvre an anti-tank gun in battle. It might not sound much, but in fact this is one of the toughest challenges P Company can throw at you—the thirteen or so minutes that it takes are some of the longest of your life. The flat sections of the log race take place on loose sand, and if you’ve ever tried to run along a sandy beach you’ll know how difficult that can be.

The afternoon of the first day sees an event known as milling. Two recruits of approximately the same size and weight are given boxing gloves, put into a ring together, and expected to slog it out for sixty seconds. That may not sound like a long time, but trust me: a minute of milling passes very slowly indeed. This isn’t a test of your boxing skills, because you have points deducted for blocking or dodging a punch. It’s a test of your ability to demonstrate controlled aggression, and to endure the aggression of the other guy. There’s no winner or loser in a milling competition, and there’s no complaining or backing out either. You either perform or you don’t. And if you don’t perform, you have to go again. Today the recruits wear mouth guards and head protectors, but when I went through P Company all we had was our gloves.

After the milling, the Crows get a weekend of rest—a weekend during which we were advised to do nothing but eat and sleep, because we had a hell of a time ahead of us over the next few days.

Monday morning means the ten-mile tab, or march. We all had to carry a thirty-pound Bergen (not including water), ammunition and individual weapon, and to pass we had to complete the march in under an hour and three-quarters. It sounds tough—it is tough—but it’s important. When a soldier is parachuted in on an operation, his objective could easily be ten miles from the drop zone, or DZ. And it would be marching like this that would get 2 Para into Goose Green during the Falklands War just a few years later. When you’re in enemy territory and your only mode of transport is your boots, you need to have the endurance to keep going.

Again, no time to rest, because next up was the trainasium. This is a particularly challenging test—a mid-air assault course the purpose of which is to test the recruits’ confidence and ability to overcome fear. Narrow planks that you could easily walk along if they were a couple of feet off the ground become a different prospect when you’re twenty metres up in the air. And jumping wide gaps that look bigger than they really are because one side is slightly lower than the other takes a lot of psychological strength when you’re that high up. You’re being tested here on your ability to control fear, and on your swift reaction to an order. When an instructor shouts ‘Go!’, you have to jump that gap, even though every cell in your body is screaming at you not to. The trainasium presents you with challenges that anyone with any sense would just walk away from, and it’s this event which is a straight pass or fail. Pass and you move on to the next stage; fail and you’re packing up your kit and heading home. I had to tell myself that so many people had done it before me but I was going to do it better. That is the mindset that six months of Recruit Company gives you.

The next day came the stretcher race. We were divided into teams of sixteen and had to carry an 180-pound steel stretcher over a distance of five miles. No more than four people were allowed to carry the stretcher at any one time, while the others carried their rifles. The stretcher race is designed to test your capacity to evacuate a wounded colleague from the battlefield, but more than that it is a fearsome test of your team-working abilities. Swapping positions, swapping weapons—all this takes coordination, communication, and, above all, the ability to work together. Winning or losing the race made no difference to your final score—the instructors judged you according to how well you presented yourself within a group.

The two-mile march, like the ten-mile march, was performed with a full pack and rifle. Time limit: eighteen minutes. And finally, the twenty-mile endurance march: full pack and rifle, and four and a half hours to complete it.

Nobody wants to fail P Company, naturally. But none of the training NCOs who have been putting the hopefuls through Recruit Company wants any of their boys to fail because it reflects badly on them. We had a chap called Rooster Barber—six foot across the shoulders and built like a brick outhouse—and he was determined that not one of his lads was going to fail. He beasted us like never before. In the days leading up to P Company he had us up before breakfast running around and jumping over benches with our rifles above our heads. Then each evening he gave us no chance to rest but blasted us with more and more fitness exercises. By the time P Company came along, we were at the peak of physical fitness. Thanks to Rooster Barber and his regular beastings, we all gave a pretty good account of ourselves in P Company and came out the other end successfully. It was a gruelling week, but all in all an amazing experience for a 17-year-old kid. At the end of it I was awarded my red beret, and that made it all worthwhile.

With the hurdle of P Company successfully negotiated, I was able to move on to parachute training at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire—an enormous, sprawling airfield the size of a fair-sized town, and with many of the facilities of one too. Living accommodation, messes, recreation facilities, all surrounded by the constant thunder of VC10 and Hercules aircraft taking off and landing. It’s a busy, bustling place, and although the huts along the edge of the complex where we were billeted were pretty basic, I was excited to be there after the long months of Recruit Company.

Our basic training was centred on an area of Brize Norton called No. 1 Parachute Training School. This was just a tiny part of an airfield, consisting of an aircraft hangar for ground-school training, and an administrative office block. On a separate part of the airfield was an area set aside for the outdoor training equipment. The two components of this were the Tower, which resembled an enormous column of scaffolding with a crane arm on the top, from which we could get used to falling through the air, and the Exit Trainer—or ‘knacker-cracker’ as it was affectionately known—from which we could practise the crucial moment when you exit the aircraft.

Parachute training is run by the RAF, which meant we were suddenly in an entirely different environment. In the Army you find yourself doubling up—or running—everywhere. At Brize Norton I was astonished to find coaches laid on to take us to the hangars. I remember turning to Woody and saying, ‘It’s a trick. They’re going to drive us ten miles out into the countryside and make us run back.’

Woody nodded ruefully. He was wise to the Army’s ways as well.

But it wasn’t a trick. No. 1 Parachute Training School isn’t like the Army. Its motto is ‘Knowledge Dispels Fear’. We weren’t here to be beasted, we were here to learn the basics of parachuting. I didn’t know at the time how much this would change my life.

To start with, we found ourselves in the large aircraft hangar where we were to undergo ground-school training. The goal is to learn how to put your parachute on, then how to land properly—with your feet and knees together and your elbows in so that you can perform a special parachute roll when you hit the ground. We practised in that hangar ad nauseam, learning the movements required for exit, flight and landing, repeating them over and over so that they became second nature. They had to be, because when it comes to a real parachute jump, you’re on your own. The time to make mistakes is in the hangar, not in the air. As time passed we progressed from a fake Hercules fuselage suspended a couple of feet above the crash mats to a piece of apparatus called the Fan. This was much like the machine I had jumped from back in Nottingham, but that seemed a long time ago now. The Fan, or a version of it, had originally been an attraction at a French funfair. When an English parachutist saw it, he brought the idea back to No. 1 Parachute Training School. It certainly gives you a taste of what it’s like to fall through the air.

We were taught how to check our parachute for problems, and what to do if it had failed to balloon properly. Before my day nobody bothered to teach you what to do if your parachute failed, because there was nothing you could do about it anyway. But in 1955 the reserve chute arrived and if things went pear-shaped, you had options. We listened especially carefully to that part of our lessons.

For the second week of our training we moved out of our hangar and over to the Tower, that huge, steel-framed apparatus on the edge of the airfield. Here we practised leaping into nothingness while attached to a harness and wire; the instructors suspended us in mid-air so that we could perform our flight drills, before lowering us to the ground to perfect our landings. And then it was the ‘knacker-cracker’, which was supposed to simulate the moment of exiting the aircraft but didn’t really come close.

Once we’d mastered the basics, the next stage was to perform some practice jumps, not out of an airplane, but from an enormous gas-filled balloon—an elderly thing that looked like the little brother of the Hindenburg. Operated by means of a winch, it had a little basket underneath, large enough for four of us plus the jump instructor. It slowly creaked up to a height of 800 feet, and once you’re up there, the only way is down. It took some courage to step out of that basket for the first time, even though for those early jumps we were using static-line parachutes. These are chutes which are attached to the aircraft—or in this case the balloon—by a webbing line. As you fall away, the line automatically opens the parachute, so you don’t have to do it yourself.

That first jump is vivid in my mind, even now. The eerie silence all around as I waited for the moment to arrive. No engine noise up here, no rush of wind. Just stillness, so high above the earth, and dry fear as the balloon, which has been rising steadily from the safety of the earth, comes to a halt. I looked down from the basket, knowing there was only one way I could get back down.

Suddenly I felt rather as if I was back on the trainasium again, waiting for the instruction to jump and knowing that, when it came, I would have no option but to follow the order.