По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

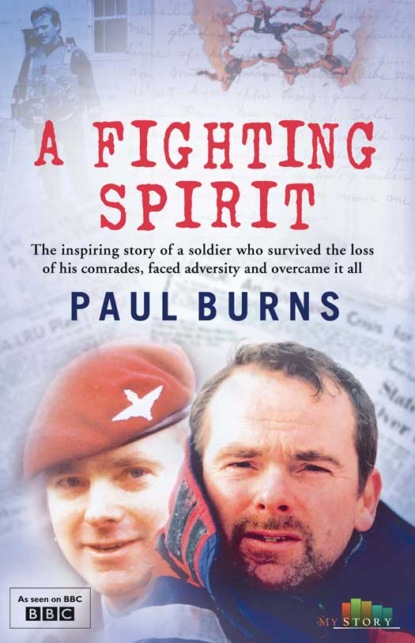

A Fighting Spirit

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When our time in Berlin was over, Scotty and Dylan—good friends I’d made in the battalion—and I made our own way back to the UK, taking a train through East Germany to Frankfurt, then back across Europe, passing through Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, and Belgium. A little holiday. A happy time. And in the brief period of leave I had before our departure for Northern Ireland I went home to Nottingham and started going out with a girl called Claire, whom I’d known since my schooldays. This was a bit of a rarity. Not many of the guys had girlfriends, because our lives were so unsettled and so dominated by the Army—first during training in Aldershot, then on deployment in Berlin.

Life seemed good, and I was looking forward to the future.

By the time the battalion arrived in Northern Ireland in July 1979, the Troubles had been blazing for over a decade. In fact there had been tensions between Protestants and Catholics in the area for almost three centuries, but it was in 1968 that things deteriorated dramatically. It was in that year that members of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, a Catholic body, marched through Londonderry in defiance of a government ban. A number of the protesters were injured by the RUC—the Royal Ulster Constabulary—that day, and this was the catalyst that sparked an increasingly devastating spiral of violence. Protestant and Catholic militants took to the streets of Belfast and Londonderry, leading to the Battle of Bogside—a two-day conflict between the Catholics and the RUC during which almost 1,500 people were injured.

The Northern Ireland government requested the help of the British Army in late 1969, and at first the soldiers were largely welcomed by the Catholic population. That didn’t last. The perception soon arose that the police and the military were more on the side of the Protestants than the Catholics, and the situation in Northern Ireland became more and more volatile—a three-way war between the unionist Catholics who wanted a united Ireland, the loyalist Protestants who wanted the Province to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the police and military, whose role it was to keep the peace but who soon became an integral part of this political struggle. British soldiers became accustomed to angry taunts from both the Catholic and the Protestant communities. They could deal with that. But everyone knew it would only be a matter of time before a member of the security forces was killed in Northern Ireland. That day arrived on 6 February 1971, when Gunner Robert Curtis, of the Royal Artillery, was shot during a riot in Belfast.

Robert Curtis’s death changed everything. When Brian Faulkner became the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland the following month, he declared war on the IRA. Internment—the practice of holding prisoners without trial—was introduced. The violence escalated. More troops died—and more civilians too—and the sectarianism grew worse. One Catholic girl, treacherous enough to go out with a British soldier, had her hair shaved before being tarred and feathered and tied to a lamp-post. That March three squaddies went home with some girls they’d met in the pub. A Republican death squad was waiting for them.

At the beginning of 1970 the IRA had split into two wings: the official IRA and the new Provisional IRA, or ‘Provos’, who were more aggressive and militant. During 1971 there were more than 1,000 bombings, and while the British forces were obliged to stick to their Rules of Engagement and only fire when they were fired upon, the Provos used whatever tactics they could to gain an advantage.

The Parachute Regiment had been deployed in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s. On 30 January 1972 an event occurred that would again deepen the Troubles, be for ever written in the history books of the Paras, and enter the public consciousness on both sides of the sectarian divide. That event came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

What really happened that day is a matter of dispute, and it’s not up to me to argue the rights and wrongs. All I know is that on that day an enormous protest march, 30,000 strong, was planned to pass through the streets of Londonderry—or Derry, as the Catholic majority in that town call it. At that time, Derry was a divided city. There was a ‘line of containment’—an invisible border beyond which the security forces seldom dared to go. On the edge of this was an area known as Aggro Corner, from where young Republicans would hurl petrol bombs at the British forces. The Army had erected barricades along the line of containment, past which the protesters were not allowed to march. Some did, and a riot ensued, during which the Paras were given the order to fire with live rounds. Thirteen marchers—including seven teenagers—were killed that day; another man died a few months later of his injuries.

Bloody Sunday became a defining moment in the Troubles. As I write this, nearly forty years later, it is still written deep in the memory of those who were affected by it. Many millions of pounds were spent on an inquiry which lasted twelve years and concluded in 2010 that the Paras were at fault for firing into the crowd that day. I have mixed feelings about this finding. For the young men in Northern Ireland, the conflict was a new kind of war—a war in which you couldn’t tell who was your friend and who was your enemy. When you join the Army you expect to have an enemy you can at least recognize, in a uniform that you can identify. Northern Ireland was very different from that. It was common for British troops to be shot at by plain-clothes snipers; the sniper would immediately pass the weapon on to an accomplice, who would run off with it and pass it on again. In circumstances like that, it’s no wonder the Paras were jumpy on Bloody Sunday. I’ve no doubt that they reacted in as professional a way as they possibly could. After Bloody Sunday, the training for British troops serving in Northern Ireland became more intense, the procedures more clearly defined. But Derry and Belfast were scary places, and to me it’s a shame that British troops were put in that position in the first place.

I was just a child at the time, not even yet an Army Cadet. But Bloody Sunday affected me too, because from that day on the Parachute Regiment was the bête noire of the IRA. Anything they could do to take one of us out would be cause for celebration.

Our period of leave between Berlin and Northern Ireland was brief—just a couple of weeks. Back home in Nottingham, my mum seemed perfectly resigned to the idea of me going to the Province. I don’t remember any great anxiety, no tears or displays of emotion. She was far more concerned about my plans to buy a motorbike, for which I’d been scrupulously saving. When she heard about that, she did wring her hands and beg me to reconsider, and I agreed, just to stop her from fretting.

Nor do I recall being nervous about my new posting. I’ve no memory of what incidents in Northern Ireland had been particularly newsworthy in the early months of 1979. For a start, I’d been abroad, but I was also just a young lad with my mind on matters other than current affairs. Perhaps I’d glance at the news headlines now and then, but I certainly wasn’t the type to read the paper cover to cover. So when the time came for me to leave, no big fuss was made. I hugged my mum and my sisters, shook my brother by the hand and made my way to the station, where I caught a train to Liverpool. It was great to meet up with the lads again and take a ferry across the water. We were all looking forward to putting our training into action, and ready for our next adventure.

The battalion was stationed in Ballykinler, a small village on the coast in County Down. It’s the most breathtaking location—three miles of desolate beach, with the granite peaks of the Mountains of Mourne in the background. Very out of the way, but that suited me fine. Ballykinler was home to an old army camp that had a long history. It had been a training camp during both World Wars, and during the Irish War of Independence it was controversially used as an internment camp. In 1974 the Provisional IRA planted a 300-pound bomb on the site, killing two soldiers and destroying some of the buildings.

From Ballykinler, we would be deployed down into ‘Bandit Country’. This was the nickname given to the southern part of County Armagh. To look at it, you would never think this was one of the most dangerous postings in the world for a British soldier. It’s a beautiful place: lush green fields, rugged moorland, rolling hills, and impressive mountains. There were no big cities in South Armagh—just small villages that felt as if they hadn’t changed much in recent times. It’s no wonder the people who live there are so fiercely protective of their homeland.

But the peace and gentleness of the landscape were deceptive. Nestled against the border with the Republic, this part of Northern Ireland had always been proudly Republican. It was a hotbed of IRA activity and a front line in the battle between them and the security forces. In the winding lanes of South Armagh, we could expect to be shot at, mortared, bombed. The area close to the border became known as the ‘Murder Circle’, because during the Troubles nearly 400 people lost their lives in this dangerous stretch of country. And of all the British soldiers killed by the IRA during the first ten years of the Troubles, nearly half died in South Armagh.

The role of the British Army in Bandit Country was to back up the police force and to be a visible sign of the rule of law. The duties of 2 Para were varied, and we rotated between different roles. We would be deployed to various fortifications and watchtowers down on the border; we would man vehicle checkpoints; we’d do escort duties and training exercises; and we’d perform patrols. Most of our patrolling was done on foot. This was for a good reason. The South Armagh branch of the IRA were specialists in roadside bomb ambushes. From my training in West Berlin I knew that to create a devastating bomb was alarmingly simple. The IRA knew that too. They placed their bombs in locations that they knew British soldiers were likely to pass, and they employed special scouts to record the security forces’ regular activities, so they knew where we were likely to be, and when. So travelling by vehicle was particularly dangerous. To the IRA it was simplicity itself to put a bomb in a culvert under the road or in a roadside ditch, where it could remain for weeks without being noticed. It became so dangerous to travel overland through South Armagh that most Army deliveries were made by helicopter into an airfield that had been set up in the small village of Bessbrook. And it was because vehicle travel was so hazardous that we tended to patrol more often on foot. There was still a risk of sniper fire, but it meant that we could vary our routes more easily and not fall prey to the Provos’ booby-traps.

During our training we had been shown a book that contained gruesome pictures of injured men. There was blood and gore everywhere, and bodies halfway between life and death. I remember looking at an image of a guy with a gunshot wound to the head and averting my eyes in disgust. My friends did the same. Revolted though we were by these pictures, we didn’t allow ourselves to be worried by them. Traumas like that had nothing to do with us. They were the kind of thing you would have expected to see in Vietnam, where there had been a real war. But in the UK? No way.

Looking back, it seems naive, but although we all knew that South Armagh was a potentially dangerous place to be, I don’t think any of us seriously thought we’d come to harm in Northern Ireland. Or if we did, we certainly never talked about it. Even the medical staff in the battalion, and the training NCOs who’d served previous tours in the Province, tended not to speak about the possibility of injury. It was taboo, off limits, something you just didn’t discuss back then. When a soldier goes on active duty, he doesn’t allow thoughts of what the enemy might do to him to prey on his mind. He can’t. Otherwise he’d never do anything.

We weren’t stupid. We knew there was the potential for rounds to be flying. We knew there was a likelihood of explosive devices—we’d been trained to search for them, after all. But for the first couple of months of our deployment in South Armagh everything seemed remarkably calm. No rounds were fired in anger; there were no bombs; we didn’t even have exposure to any anti-British feeling, and as far as I knew, that was true for the whole of 2 Para. All the little jobs I went on ran smoothly.

It seems strange to say it now, but I enjoyed myself during those first two months. I remembered the motto of No.1 Parachute Training School—‘Knowledge Dispels Fear’—and it was true. I felt that I’d been equipped with the right knowledge to counter anything that might come along, and I was too young—too green, I suppose—to worry about death or injury.

Some events cannot be predicted. Some horrors are too dreadful to imagine. They come without warning, out of the blue, when you’re looking the other way. And it doesn’t matter how long life has been uneventful. It doesn’t matter how prepared you are, or confident in your abilities. Sometimes it only takes a moment for life to change beyond recognition.

Knowledge might well dispel fear. But had I known that what was around the corner would be worse than any of the gory images of wounded soldiers we had been shown, I don’t doubt that I would have been filled with the kind of fear that no knowledge in the world could ever dispel.

Chapter Four Warrenpoint (#ulink_d9eac3ab-9aac-5205-a7e8-7ed8d72aaecf)

Monday, 27 August 1979 was a hot, sunny bank holiday. The kind of day that would, in other circumstances, make you glad to be near the sea. Perhaps if it had been overcast, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, one of the Royal Navy’s most prestigious officers, might not have decided to go fishing.

Lord Mountbatten had a holiday home in Mullaghmore, County Sligo, on the north-west coast of Ireland. He had a 30-foot boat, the Shadow V, moored unguarded in the harbour of that small seaside village, and it was his custom to go lobster-potting in Donegal Bay. The Irish police warned him not to go out on his boat that day, but he decided it would be safe. He was wrong. The previous night a member of the IRA had slipped on board the boat and planted a fifty-pound bomb with a remote-control detonator. The following day, together with members of his family and a small crew, Mountbatten set off looking for lobsters.

He never found them. As the Shadow V headed for Donegal Bay, a second IRA man detonated the device. Mountbatten wasn’t killed instantly: he was severely wounded and perished soon after by drowning. Three others were killed in the blast: his 14-year-old grandson, his daughter’s mother-in-law, and a 15-year-old crew member. It was a terrible atrocity, and would have been enough for that bank holiday Monday to go down as one of the darkest days of the Troubles. But it wasn’t over yet.

As part of A Company, my mates and I were due to relieve 2 Para’s Support Company at the town of Newry in County Down, just near the county border with Armagh. The Troubles had hit Newry hard, with several fatalities over the previous few years, and the Paras’ role there was to reinforce the police presence. As far as we were concerned, it was just another day on rotation, and we spent the morning in camp at Ballykinler, preparing to be transported down to Newry.

It was the habit of our commanders at Ballykinler to work out different possible routes between two points. That way we could select routes at random and increase our chances of thwarting the IRA scouts that we knew were trying to identify which roads we were most likely to use, and when. The route that was selected for our journey that day was to take us south on the A2, along the coast, before heading west along the estuary of Carling-ford Lough, through the town of Warrenpoint, and up into Newry. Of all the routes we could take, this was possibly the most dangerous, because just above Warrenpoint the estuary thinned at a place called Narrow Water. On the other side of the estuary was the Republic of Ireland, where thick forest ran down to the coast. From the IRA’s point of view, it was a good place for an ambush, because they could lie hidden in wait on the Republic’s side of the water with a clear view of the traffic passing on our side, detonate a bomb by remote control, and instantly disappear. Moreover, this was the route that a Royal Marine patrol took in a Land Rover fairly frequently to check on a nearby container terminal. But to avoid this route entirely would just make it more likely that we’d be hit on one of the alternative routes. We had to keep the enemy guessing.

There were three vehicles that were to take A Company to Newry that day: two four-ton lorries and a Land Rover. Nowadays soldiers in war zones are—quite rightly—given vehicles that are specially designed to withstand the blast of an IED, but there was nothing unusually robust about these vehicles. And as my mates and I got ready to leave, we put on our flak vests, but we also donned our red berets rather than wearing helmets. Partly this was out of defiance, but there was another reason for us not to want to look too heavily armed. In the eyes of large parts of the population of Northern Ireland, we were an occupying force. We were all very mindful of the battle for hearts and minds, and we knew that if we appeared too aggressive it would make that battle harder to win.

‘Hurry up and wait!’ is an expression you hear a lot in the British Army, and there was a lot of hanging around that day, waiting to get the order to leave Ballykinler and set off for Newry. We were going to be stationed in the town for some time, so we had all our bags packed and ready to go, and I remember killing time in the little ‘choggy shop’, or café, at base, playing with the lads on the Space Invaders machine—the latest thing at the time. It was very hot and everyone was impatient to get off, as well as a little bit anxious about the dangers of heading down along the border. Finally we were ready to leave: Woody, Jonesy, Dylan and I climbed up into one of the four-tonners together, along with Tom Caughy, Private Gary Barnes, whom everyone called Barney, and one other guy from a different platoon. Corporal Johnny Giles was driving.

There were only eight of us in our vehicle, six in the back, two in the front, because we were also carrying the company ammunition—boxes of rifle rounds, mortar rounds, grenades, link for the machine-gun. It was mid-afternoon when we set off. I can’t remember who was sitting next to me, but I know that I was at the back of the lorry, on the tailgate, my rifle at the ready so I could keep a lookout for anything suspicious. Tom changed seats with Barney, a close friend of his who’d been with him in the junior company. Barney was a real character. Good fun. Solid. He was struggling with the exhaust fumes that were pumping into the lorry, so Tom offered to swap places. Our three-vehicle convoy trundled out of Ballykinler, and although we were just shooting the breeze in our usual way, we were all finding it unbearably hot and just wanted to get to our destination.

That is the last memory I have of the day that was to change so many people’s lives for ever. And it is the last memory six of my friends and colleagues in that truck would ever have.

I can only relate the horrors of the next few hours by piecing together what other people have told me.

It was a little before five o’clock when our platoon of approximately twenty-six soldiers approached Warrenpoint. Our convoy had reached the dual carriageway that ran alongside Narrow Water, and was passing a lay-by where a lorry loaded with bales of hay was parked up. The lorry contained an 800-pound fertilizer bomb, packed in beer kegs and attached to a radio-controlled detonator. As far as I know, the IRA had set up this roadside bomb in the hope of hitting one of the Marine patrols that used this road regularly. When they saw a company of red berets coming—the devils of Bloody Sunday—they must have been doing somersaults of joy at their luck.

The lorry in which my mates and I were travelling was the last one in the convoy. The first two passed the roadside bomb safely. It was as our vehicle drew alongside it that two Provos, safely hidden on the other side of the estuary, detonated the device.

The noise must have been enormous, but I have no memory of it, or of any of the events that followed.

Our truck was hurled onto its side and into the central reservation, its chassis ripped apart, a wrecked, mangled heap of burning metal. The ammunition that we were carrying started to ignite, causing hundreds of tiny explosions. Bodies were flung from the wreckage and into the road. Johnny Giles lay slumped across the steering wheel as if sleeping. He would never wake up. The air filled with the sound of the screams of the wounded and the smell of burning flesh, which most likely included mine. My body was on fire in the minutes after the explosion. I lay there unconscious in the searing heat while the skin on my face and arms charred and my legs burned to the bone.

As soon as the bomb exploded, the Land Rover in front crossed the central reservation of the A2 and spun round so that it was facing the way it came. The other lorry found cover under some nearby trees. Confusion was everywhere. The surviving members of A Company heard the sound of our ammo detonating and assumed that a sniper was firing on them. And so they fired back, aiming their rounds across the narrow estuary towards the Republic. In doing so, they killed one innocent civilian and injured another.

Our platoon commander desperately tried to raise HQ on the radio, but for some reason the radio communications were down. Fortunately a Wessex helicopter picked up the platoon commander’s call and relayed what had happened to HQ. The chopper was given the order to pick up a medical team and a quick-reaction force, then immediately return to Warrenpoint. Firefighters were on the scene in minutes to help put out the flames, including those that were eating up my own flesh.

As soon as word of the blast reached Newry, a quick-reaction force comprising two Land Rovers full of Paras was immediately dispatched to the site. In addition Lieutenant Colonel David Blair of the Queen’s Own Highlanders, who happened to be in the air in a small helicopter at the time, diverted to the scene.

In the Army there are standard operating procedures, or SOPs—instructions about what to do under certain circumstances—and these were followed to the letter. On the other side of the road, perhaps 150 metres on from the blast point, there was a granite gate-lodge opposite the entrance to Narrow Water Castle, a well-known beauty spot. As the quick-reaction force, Lieutenant Colonel Blair, and our OC, Major Fursman, congregated at the blast site, they set up an incident control point inside the gate-lodge. It was the sensible thing to do as it was close to where they needed to be and could be easily defended if necessary.

However, the IRA’s scouts had done their work well. They had studied the Army’s SOPs. They knew that the gate-lodge was the most likely place to set up an incident control point, and so they had planted a second device there, hidden in some innocuous-looking milk pails. In terms of loss of life, this bomb would prove to be even more devastating than the first. The bombers, hidden on the other side of the water, detonated the second device just as the gate-lodge was full of soldiers.

The whole building collapsed. Chunks of rock the size of footballs shot through the air and landed almost 100metres away. By this time I had been transferred to a Wessex. The chopper was just feet above the ground when its windows were blasted in as it attempted to casevac me and others to the safety of Musgrave Park Hospital in Belfast.

Nowadays we hear of bombings almost daily, of IEDs in Afghanistan or atrocities in Iraq. Perhaps we don’t stop to think about what it really means. Even I find it hard to imagine what the sight of that massacre at Warrenpoint must have looked like. Hard to imagine the horror and even now, so many years later, hard to recount what I’m told it looked like. A part of me feels reluctant to do so. Narrow Water is a beauty spot, but there was nothing beautiful about it that day. There were two enormous craters where the two bombs had been located. Horrifically wounded men were strewn around the road. But worst of all, the area was littered with human body parts. Gobbets of flesh hung from trees, so far up that even the firemen’s ladders were unable to reach them. Limbs lay in the grass verge and on the road. Entire torsos had been separated from legs. The same went for heads. The living were so appalled by the sight that many of them had to vomit into the bushes. And the blasts were so severe that some of the guys were never found. The epaulettes of his uniform were all that remained of Lieutenant Colonel David Blair; the rest of his body had been utterly destroyed. And when a dive team arrived, one of them made a gruesome discovery in the estuary. It was a human face, still recognizable as that of Major Fursman. It had been ripped whole from its owner’s skull. The police said they had never seen such carnage as they witnessed that day.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: