По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

Hag Fold

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hag Fold

Paul Finch

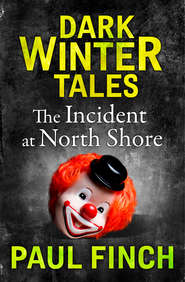

**A horror short story from #1 bestseller, Paul Finch. Part of the Dark Winter Tales series: unputdownable reads for cold winter nights…**Living next to the children’s home on Hag Fold, young Timmy only has eyes for Erika – a little girl his mother won’t let him play with.As they grow up, Timmy and Erika go their separate ways, until a chance meeting brings them both back to the place they once lived.But Hag Fold is now a dangerous place. Over the years, a number of women have been strangled to death – but the killer has never been found. And it’s soon clear though that the murderer is still on the prowl…As the nights draw in, get hooked on this dark and suspenseful tale – the perfect read for fans of Mark Edwards and Peter James.

Hag Fold

Paul Finch

Copyright (#ulink_0b14b121-483f-5e84-8072-e08120ed2ffe)

Published by Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers 2016

First published in paperback and hardback in One Monster Is Not Enough by Gray Friar Press, 2012

Copyright © Paul Finch 2016

Cover design © Debbie Clement 2016

Paul Finch asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780008173760

Version: 2015-12-18

Contents

Cover (#udcabf58d-1d78-5bb0-89a5-2251dee2a2bf)

Title Page (#ud0cea0e4-d7c1-555c-9908-33b2bb64a747)

Copyright (#u7b68aa64-6d56-5bd1-9e2e-2ef40dd09aa1)

Hag Fold (#u5191f34b-8fb2-5d1d-9b66-81ca186bc606)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

On September 12th 1978, the body of a 19-year-old waitress was found wrapped in a carpet and dumped in a railway underpass near to the council playing fields on Hag Fold Avenue, north Manchester. The girl had been raped and beaten, but death had resulted from a single blow to the throat, delivered with such force that it had completely crushed her windpipe.

Every day he heard the children playing on the other side of the wall. Timmy was only very young, himself; so young that he wasn’t even allowed out of his own backyard, but at least he was able to listen – to their giggles and their squeals, to the pitter-patter of their feet as they charged up and down.

Timmy would sit for hours, picking at the moss between the flagstones, wondering who they were, wondering how many of them were over there. It sounded like a lot. To Timmy, who, apart from his mother, only ever saw the coal-man and the rent-man, this seemed incredible. The children’s house never gave him any clues. It was a mirror image of his own: semi-detached, but tall and narrow and built from sooty brick. The curtains in its windows looked slightly shabbier than the ones in Timmy’s, while its paintwork was cracked and flaking. On one occasion he approached his mother about it, asking who the children were and if he could perhaps go round and play with them.

His mother had simply stared at him, the eyes like marbles in her thin, hard face.

“You will do no such thing,” she said. “Isn’t it bad enough that we have to live in a neighbourhood like this without you getting involved with the likes of them! Christ Almighty, that’s the last thing we want!”

*

Once you’ve crossed that essential Rubicon and taken your first life, it’s easy to do it again. All that matters is the planning and logistics.

The first time I killed, it was three or four at once: Argentine soldiers. Raw recruits, I dare say; muddy, terrified, underfed, but still armed with a GPMG and blazing at us from their dug-out as we assaulted their lines at Goose Green in May 1982. May is late autumn in the South Atlantic, so it was pitch-black and driving with bitter rain. I remember pinpointing them by their tracer, which cut across the battlefront in vivid streaks.

It was pandemonium that dawn. Clouds of orange flame ballooned on the horizon; the ground was churned to quagmires; SAM missiles flocked by overhead, screaming like devils. In such a battery of sound and pyrotechnics, the Argie machine-gunners didn’t notice me ’til it was too late. I launched a grenade into the middle of them. They didn’t even notice that. It flashed and roared and minced at least two of them outright. A third staggered out, a ragged, smouldering, inhuman shape; an overhead flare showed him all blood and tatters, clutching the stump of a severed arm. I levelled my SLR and punched him full of holes. The next one came out screaming hysterically, shooting in all directions. A bad time for my clip to run dry. I dived into the mud as he came towards me. He’d totally lost it, and didn’t spot me as I tripped him and jumped onto him from behind. He was shrieking, frothing at the mouth, struggling wildly. I think he thought I was a comrade, pulling him down to protect him. Ironically, that made him fight all the harder, made him determined not to surrender. Not that I’d have accepted it. You see, combat regiments are all about killing. They pick you to serve in them because they know you will kill. They teach you to kill. They encourage you to kill. You become a fully-trained professional killer. That is your job. And until you actually do it – and enjoy it into the bargain – you aren’t part of the club.

So I killed him. Knifed him. Ten or twelve times before he finally lay still.

*

On November 28th 1979, the remains of a 26-year-old prostitute and heroin addict were discovered in a burned-out garage on NCB wasteland in the Hag Fold district of Manchester. She had died from asphyxiation, having been garrotted with her own bra, but only after violent rape and prolonged torture with a cigarette lighter.

The first time Timmy saw them was from the top of the coal bunker, but it didn’t give him a great view. Far better was to sneak into the entry between the two houses and peep on the children through the planks in their back gate.

By this time he’d found out who they were, or rather what they were.

Orphans. Or kids who might as well be orphans. The Social Services owned that house, and all the children living there were ‘in care’. They’d either been neglected by their real parents, abused in some way or just kicked out. The first time he heard about this, Timmy felt a unique thrill of horror. His own home life, strictly regimented by the awesome figure of his mother, often left him desperately miserable, but, frequent though the strappings were, not to mention the nights without tea or TV, he could never imagine reaching the situation where his parent grew so irate with him that she’d actually show him the door.

So he watched the children through the cracks in their back gate with a new, morbid wonder. At first he’d expected to see them in rags, the way the paupers had been on that film his mother had taken him to see at the cinema, Oliver! But in this respect he was disappointed. Apparently, they dressed much the way other children did; the girls in sandals, socks and flowered dresses, the lads in short pants and t-shirts. Their very ordinariness was the thing that surprised him most. Their hair was always neatly combed and cut; they didn’t seem especially unhappy – the girls skipped cheerfully with their ropes, the boys played football or with toy soldiers.

However, there was one thing slightly different about them – their age-range.

Timmy was at infant school now, and finally starting to associate with other kids. But these were his classmates, and all were of a similar age to him. The children in the yard next door seemed to be all kinds of different ages. There were six of them in total, three boys and three girls, and they ranged from the youngest boy, who could only have been about three, to the eldest girl, who was ten at least.

That eldest girl was of particular interest to Timmy. He’d only been peeping on them for a couple of weeks when it struck him that she was the real object of his attention. She was tall and slim, with short dark hair, bright eyes and cherry-red lips. She was, Timmy would come to realise in later life, extraordinarily beautiful for one so young, but it wasn’t just this that attracted him. To the other children this girl was clearly the older sister they’d never had. She was the centre of every game, the decider of every issue, the giver of all instructions – though not in the harsh, threatening way that Timmy’s mother was. The rest of the children adored this girl, flocking around her in play, taking their cuts and bumps to her if they fell.

Timmy watched with envy at the love she showed them. But he’d long ago learned not to ask questions in which words like ‘why’ and ‘not’ featured – why did he not have that?, why did he not have this? As far as his mother was concerned, he already had too much – so he mutely accepted that the girl was no part of his life, and felt increasingly hostile to the rest of the children because she was so much a part of theirs. The thought that they were only in the care home because they’d suffered in some way, or had been abandoned, became a source of pleasure to him. He’d gloat to himself as he watched them, wondering excitedly about the things they might have experienced.

The idea that the older girl had also gone through something bad occurred to him as well. He didn’t gloat in her case, but it gave him a funny feeling all the same. A feeling that wasn’t totally displeasing.

*

Paul Finch

**A horror short story from #1 bestseller, Paul Finch. Part of the Dark Winter Tales series: unputdownable reads for cold winter nights…**Living next to the children’s home on Hag Fold, young Timmy only has eyes for Erika – a little girl his mother won’t let him play with.As they grow up, Timmy and Erika go their separate ways, until a chance meeting brings them both back to the place they once lived.But Hag Fold is now a dangerous place. Over the years, a number of women have been strangled to death – but the killer has never been found. And it’s soon clear though that the murderer is still on the prowl…As the nights draw in, get hooked on this dark and suspenseful tale – the perfect read for fans of Mark Edwards and Peter James.

Hag Fold

Paul Finch

Copyright (#ulink_0b14b121-483f-5e84-8072-e08120ed2ffe)

Published by Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers 2016

First published in paperback and hardback in One Monster Is Not Enough by Gray Friar Press, 2012

Copyright © Paul Finch 2016

Cover design © Debbie Clement 2016

Paul Finch asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780008173760

Version: 2015-12-18

Contents

Cover (#udcabf58d-1d78-5bb0-89a5-2251dee2a2bf)

Title Page (#ud0cea0e4-d7c1-555c-9908-33b2bb64a747)

Copyright (#u7b68aa64-6d56-5bd1-9e2e-2ef40dd09aa1)

Hag Fold (#u5191f34b-8fb2-5d1d-9b66-81ca186bc606)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

On September 12th 1978, the body of a 19-year-old waitress was found wrapped in a carpet and dumped in a railway underpass near to the council playing fields on Hag Fold Avenue, north Manchester. The girl had been raped and beaten, but death had resulted from a single blow to the throat, delivered with such force that it had completely crushed her windpipe.

Every day he heard the children playing on the other side of the wall. Timmy was only very young, himself; so young that he wasn’t even allowed out of his own backyard, but at least he was able to listen – to their giggles and their squeals, to the pitter-patter of their feet as they charged up and down.

Timmy would sit for hours, picking at the moss between the flagstones, wondering who they were, wondering how many of them were over there. It sounded like a lot. To Timmy, who, apart from his mother, only ever saw the coal-man and the rent-man, this seemed incredible. The children’s house never gave him any clues. It was a mirror image of his own: semi-detached, but tall and narrow and built from sooty brick. The curtains in its windows looked slightly shabbier than the ones in Timmy’s, while its paintwork was cracked and flaking. On one occasion he approached his mother about it, asking who the children were and if he could perhaps go round and play with them.

His mother had simply stared at him, the eyes like marbles in her thin, hard face.

“You will do no such thing,” she said. “Isn’t it bad enough that we have to live in a neighbourhood like this without you getting involved with the likes of them! Christ Almighty, that’s the last thing we want!”

*

Once you’ve crossed that essential Rubicon and taken your first life, it’s easy to do it again. All that matters is the planning and logistics.

The first time I killed, it was three or four at once: Argentine soldiers. Raw recruits, I dare say; muddy, terrified, underfed, but still armed with a GPMG and blazing at us from their dug-out as we assaulted their lines at Goose Green in May 1982. May is late autumn in the South Atlantic, so it was pitch-black and driving with bitter rain. I remember pinpointing them by their tracer, which cut across the battlefront in vivid streaks.

It was pandemonium that dawn. Clouds of orange flame ballooned on the horizon; the ground was churned to quagmires; SAM missiles flocked by overhead, screaming like devils. In such a battery of sound and pyrotechnics, the Argie machine-gunners didn’t notice me ’til it was too late. I launched a grenade into the middle of them. They didn’t even notice that. It flashed and roared and minced at least two of them outright. A third staggered out, a ragged, smouldering, inhuman shape; an overhead flare showed him all blood and tatters, clutching the stump of a severed arm. I levelled my SLR and punched him full of holes. The next one came out screaming hysterically, shooting in all directions. A bad time for my clip to run dry. I dived into the mud as he came towards me. He’d totally lost it, and didn’t spot me as I tripped him and jumped onto him from behind. He was shrieking, frothing at the mouth, struggling wildly. I think he thought I was a comrade, pulling him down to protect him. Ironically, that made him fight all the harder, made him determined not to surrender. Not that I’d have accepted it. You see, combat regiments are all about killing. They pick you to serve in them because they know you will kill. They teach you to kill. They encourage you to kill. You become a fully-trained professional killer. That is your job. And until you actually do it – and enjoy it into the bargain – you aren’t part of the club.

So I killed him. Knifed him. Ten or twelve times before he finally lay still.

*

On November 28th 1979, the remains of a 26-year-old prostitute and heroin addict were discovered in a burned-out garage on NCB wasteland in the Hag Fold district of Manchester. She had died from asphyxiation, having been garrotted with her own bra, but only after violent rape and prolonged torture with a cigarette lighter.

The first time Timmy saw them was from the top of the coal bunker, but it didn’t give him a great view. Far better was to sneak into the entry between the two houses and peep on the children through the planks in their back gate.

By this time he’d found out who they were, or rather what they were.

Orphans. Or kids who might as well be orphans. The Social Services owned that house, and all the children living there were ‘in care’. They’d either been neglected by their real parents, abused in some way or just kicked out. The first time he heard about this, Timmy felt a unique thrill of horror. His own home life, strictly regimented by the awesome figure of his mother, often left him desperately miserable, but, frequent though the strappings were, not to mention the nights without tea or TV, he could never imagine reaching the situation where his parent grew so irate with him that she’d actually show him the door.

So he watched the children through the cracks in their back gate with a new, morbid wonder. At first he’d expected to see them in rags, the way the paupers had been on that film his mother had taken him to see at the cinema, Oliver! But in this respect he was disappointed. Apparently, they dressed much the way other children did; the girls in sandals, socks and flowered dresses, the lads in short pants and t-shirts. Their very ordinariness was the thing that surprised him most. Their hair was always neatly combed and cut; they didn’t seem especially unhappy – the girls skipped cheerfully with their ropes, the boys played football or with toy soldiers.

However, there was one thing slightly different about them – their age-range.

Timmy was at infant school now, and finally starting to associate with other kids. But these were his classmates, and all were of a similar age to him. The children in the yard next door seemed to be all kinds of different ages. There were six of them in total, three boys and three girls, and they ranged from the youngest boy, who could only have been about three, to the eldest girl, who was ten at least.

That eldest girl was of particular interest to Timmy. He’d only been peeping on them for a couple of weeks when it struck him that she was the real object of his attention. She was tall and slim, with short dark hair, bright eyes and cherry-red lips. She was, Timmy would come to realise in later life, extraordinarily beautiful for one so young, but it wasn’t just this that attracted him. To the other children this girl was clearly the older sister they’d never had. She was the centre of every game, the decider of every issue, the giver of all instructions – though not in the harsh, threatening way that Timmy’s mother was. The rest of the children adored this girl, flocking around her in play, taking their cuts and bumps to her if they fell.

Timmy watched with envy at the love she showed them. But he’d long ago learned not to ask questions in which words like ‘why’ and ‘not’ featured – why did he not have that?, why did he not have this? As far as his mother was concerned, he already had too much – so he mutely accepted that the girl was no part of his life, and felt increasingly hostile to the rest of the children because she was so much a part of theirs. The thought that they were only in the care home because they’d suffered in some way, or had been abandoned, became a source of pleasure to him. He’d gloat to himself as he watched them, wondering excitedly about the things they might have experienced.

The idea that the older girl had also gone through something bad occurred to him as well. He didn’t gloat in her case, but it gave him a funny feeling all the same. A feeling that wasn’t totally displeasing.

*