По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

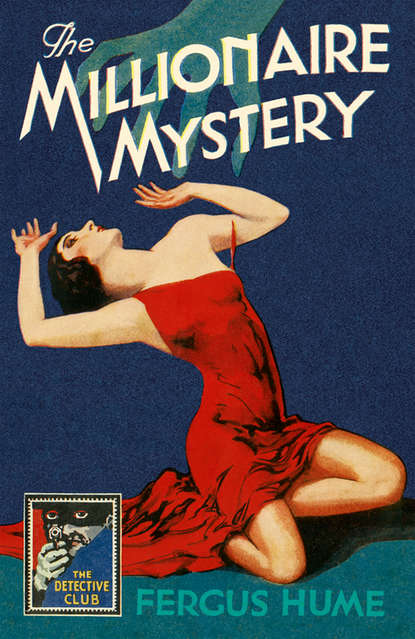

The Millionaire Mystery

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When his eyes had become more accustomed to the half-light, the first object upon which they fell was a stiff human form stretched on the mud floor—a body with a handkerchief over the face. Yelling with terror, Cicero hurled himself out again.

‘Marlow’s body!’ he gasped. ‘They’ve put it here!’

With feverish haste he produced a corkscrew knife, and opened his whisky bottle. A fiery draught gave him courage. He ventured back into the hut and knelt down beside the body. Over the heart gaped an ugly wound, and the clothes were caked with blood. He gasped again.

‘No fit this, but murder! Stabbed to the heart! And Joe—what does Joe know about this—and my employer? Lord!’

He snatched the handkerchief from the face, and fell back on his knees with another cry, this time of wonderment rather than of terror. He beheld the dead man’s fair beard and bald head.

‘Dr Warrender! And he was alive last night! This is murder indeed!’

Then his nerves gave way utterly, and he began to cry like a frightened child.

‘Murder! Wilful and horrible murder!’ wept the professor of elocution and eloquence.

CHAPTER III (#u6c673537-f57b-564e-83f0-e505de336ec2)

AN ELEGANT EPISTLE

ON Bournemouth cliffs, where pine-trees cluster to the edge, sat an elderly spinster, knitting a homely stocking. She wore, in spite of the heat, a handsome cashmere shawl, pinned across her spare shoulders with a portrait brooch, and that hideous variety of Early Victorian head-gear known as the mushroom hat. From under this streamed a frizzy crop of grey curls, which framed a rosy, wrinkled face, brightened by twinkling eyes. These, sparkling as those of sweet seventeen, proved that their owner was still young in heart. This quaint survival of the last century knitted as assiduously as was possible under the circumstances, for at a discreet distance were two young people, towards whom she acted the part of chaperon. Doubtless such an office is somewhat out-of-date nowadays; but Miss Victoria Parsh would rather have died than have left a young girl alone in the company of a young man.

Yet she knew well enough that this young man was altogether above reproach, and, moreover, engaged by parental consent to the pretty girl to whom he was talking so earnestly. And no one could deny that Sophy Marlow was indeed charming. There was somewhat of the Andalusian about her. Not very tall, shaped delicately as a nymph, she well deserved Alan Thorold’s name. He called her the ‘Midnight Fairy’, and, indeed, she looked like a brunette Titania. Her complexion was dark, and faintly flushed with red; her mouth and nose were exquisitely shaped, while her eyes were wells of liquid light—glorious Spanish orbs. About her, too, was that peculiar charm of personality which defies description.

Alan her lover was not tall, but uncommonly well-built and muscular, as fair as Sophy was dark—of that golden Saxon race which came before the Dane. Not that he could be called handsome. He was simply a clean, clear-skinned, well-groomed young Englishman, such as can be seen everywhere. Of a strong character, he exercised great control over his somewhat frivolous betrothed.

Miss Vicky, as the little spinster was usually called, cast romantic glances at the dark head and the fair one so close to one another. As a rule she would have been shocked at such a sight, but she knew how keenly Sophy grieved for the death of her father, and was only too willing that the girl should be comforted. And Miss Vicky occasionally touched the brooch, which contained the portrait of a red-coated officer. She also had lived in Arcady, but her Lieutenant had been shot in the Indian Mutiny, and Miss Vicky had left Arcady after a short sojourn, for a longer one in the work-a-day world. At once, she had lost her lover and her small income, and, like many another lonely woman, had had to turn to and work. But the memory of that short romance kept her heart young, hence her sympathy with this young couple.

‘Poor dear father!’ sighed Sophy, looking at the sea below, dotted with white sails. ‘I can hardly believe he is gone. Only two weeks ago and he was so well, and now—oh! I was so fond of him! We were so happy together! He was cold to everyone else, but kindly to me! How could he have died so suddenly, Alan?’

‘Well, of course, dear, a fit is always sudden. But try and bear up, Sophy dear. Don’t give way like this. Be comforted.’

She looked up wistfully to the blue sky.

‘At all events, he is at peace now,’ she said, her lip quivering. ‘I know he was often very unhappy, poor father! He used to sit for hours frowning and perplexed, as if there was something terrible on his mind.’

Alan’s face was turned away now, and his brow was wrinkled. He seemed absorbed in thought, as though striving to elucidate some problem suggested by her words.

Wrapped up in her own sorrow, the girl did not notice his momentary preoccupation, but continued:

‘He never said good-bye to me. Dr Warrender said he was insensible for so long before death that it was useless my seeing him. He kept me out of the room, so I only saw him—afterwards. I’ll never forgive the doctor for it. It was cruel!’

She sobbed hysterically.

‘Sophy,’ said Alan suddenly, ‘had your father any enemies?’

She looked round at him in astonishment.

‘I don’t know. I don’t think so. Why should he? He was the kindest man in the world.’

‘I am sure he was,’ replied the young man warmly; ‘but even the kindest may have enemies.’

‘He might have made enemies in Africa,’ she said gravely. ‘It was there he made his money, and I suppose there are people mean enough to hate a man who is successful, especially if his success results in a fortune of some two millions. Father used to say he despised most people. That was why he lived so quietly at the Moat House.’

‘It was particularly quiet till you came, Sophy.’

‘I’m sure it was,’ she replied, with the glimmer of a smile. ‘Still, although he had not me, you had your profession.’

‘Ah! my poor profession! I always regret having given it up.’

‘Why did you?’

‘You know, Sophy. I have told you a dozen times. I wanted to be a surgeon, but my father always objected to a Thorold being of service to his fellow-creatures. I could never understand why. The estate was not entailed, and by my father’s will I was to lose it, or give up all hope of becoming a doctor. For my mother’s sake I surrendered. But I would choose to be a struggling surgeon in London any day, if it were not for you, Sophy dear.’

‘Horrid!’ ejaculated Miss Marlow, elevating her nose. ‘How can you enjoy cutting up people? But don’t let us talk of these things; they remind me of poor dear father.’

‘My dear, you really should not be so morbid. Death is only natural. It is not as though you had been with him all your life, instead of merely three years.’

‘I know; but I loved him none the less for that. I often wonder why he was away so long.’

‘He was making his fortune. He could not have taken you into the rough life he was leading in Africa. You were quite happy in your convent.’

‘Quite,’ she agreed, with conviction. ‘I was sorry to leave it. The dear sisters were like mothers to me. I never knew my own mother. She died in Jamaica, father said, when I was only ten years old. He could not bear to remain in the West Indies after she died, so he brought me to England. While I was in the convent I saw him only now and again until I had finished my education. Then he took the Moat House—that was five years ago, and two years after that I came to live with him. That is all our history, Alan. But Joe Brill might know if he had any enemies.’

‘Yes, he might. He lived thirty years with your father, didn’t he? But he can keep his own counsel—no one better.’

‘You are good at it too, Alan. Where were you last night? You did not come to see me.’

He moved uneasily. He had his own reasons for not wishing to give a direct answer.

‘I went for a long walk—to—to—to think out one or two things. When I got back it was too late to see you.’

‘What troubled you, Alan? You have looked very worried lately. I am sure you are in some trouble. Tell me, dear; I must share all your troubles.’

‘My dearest, I am in no trouble’—he kissed her hand—‘but I am your trustee, you know and it is no sinecure to have the management of two millions.’

‘It’s too much money,’ she said. ‘Let us dispose of some of it, then you need not be worried. Can I do what I like with it?’

‘Most of it—there are certain legacies. I will tell you about them later.’

‘I am afraid the estate will be troublesome to us, Alan. It’s strange we should have so much money when we don’t care about it. Now, there is Dr Warrender, working his life out for that silly extravagant wife of his!’

‘He is very much in love with her, nevertheless.’

‘I suppose that’s why he works so hard. But she’s a horrid woman, and cares not a snap of her fingers for him—not to speak of love! Love! why, she doesn’t know the meaning of the word. We do!’ And, bending over, Sophy kissed him.

Then promptly there came from Miss Parsh the reminder that it was time for tea.

‘Very well, Vicky, I dare say Alan would like you to give him a cup,’ replied Sophy.