По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

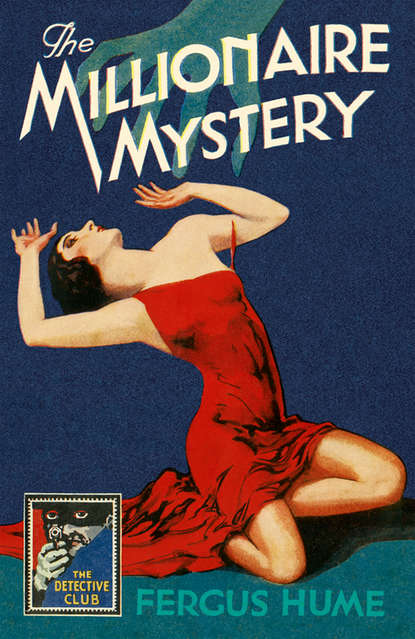

The Millionaire Mystery

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Frivolous as ever, Sophia! I give up a hope of forming your character—now!’

‘Alan is doing that,’ replied the girl.

In spite of her sorrow, Sophy became fairly cheerful on the way back to the hotel. Not so Alan. He was silent and thoughtful, and evidently meditating about the responsibilities of the Marlow estate. As they walked along the parade with their chaperon close behind, they came upon a crowd surrounding a fat man dressed in dingy black. He was reciting a poem, and his voice boomed out like a great organ. As they passed, Alan noticed that he darted a swift glance at them, and eyed Miss Marlow in a particularly curious manner. The recitation was just finished, and the hat was being sent round. Sophy, always kind-hearted, dropped in a shilling. The man chuckled.

‘Thank you, lady,’ said he; ‘the first of many, I hope.’

Alan frowned, and drew his fiancée away. He took little heed of the remark at the time; but it occurred to him later when circumstances had arisen which laid more stress on its meaning.

Miss Vicky presided over the tea—a gentle feminine employment in which she excelled. She did most of the talking; for Sophy was silent, and Alan inclined to monosyllables. The good lady announced that she was anxious to return to Heathton.

‘The house weighs on my mind,’ said she, lifting her cup with the little finger curved. ‘The servants are not to be trusted. I fear Mrs Crammer is addicted to ardent spirits. Thomas and Jane pay too much attention to one another. I feel a conviction that, during my absence, the bonds of authority will have loosened.’

‘Joe,’ said Alan, setting down his cup; ‘Joe is a great disciplinarian.’

‘On board a ship, no doubt,’ assented Miss Vicky; ‘but a rough sailor cannot possibly know how to control a household. Joseph is a fine, manly fellow, but boisterous—very boisterous. It needs my eye to make domestic matters go smoothly. When will you be ready to return, Sophy, my dear?’

‘In a week—but Alan has suggested that we should go abroad.’

‘What! and leave the servants to wilful waste and extravagance? My love!’—Miss Vicky raised her two mittened hands—‘think of the bills!’

‘There is plenty of money, Vicky.’

‘No need there should be plenty of waste. No; if we go abroad, we must either shut up the house or let it.’

‘To the Quiet Gentleman?’ said Sophy, with a laugh.

Alan looked up suddenly.

‘No, not to him. He is a mysterious person,’ said Miss Vicky. ‘I do not like such people, though I dare say it is only village gossip which credits him with a strange story.’

‘Just so,’ put in Alan. ‘Don’t trouble about him.’

Miss Vicky was still discussing the possibility of a trip abroad, when the waiter entered with a note for Sophy.

‘It was delivered three hours ago,’ said the man apologetically, ‘and I quite forgot to bring it up. So many visitors, miss,’ he added, with a sickly smile.

Sophy took the letter. The envelope was a thick creamy one, and the writing of the address elegant in the extreme.

‘Who delivered it?’ she asked.

‘A fat man, miss, with a red face, and dressed in black.’

Alan’s expression grew somewhat anxious.

‘Surely that describes the man we saw reciting?’

‘So it does.’ Sophy eyed the letter dubiously. ‘Had he a loud voice, Simmonds?’

‘As big as a bell, miss, and he spoke beautiful: but he wasn’t gentry, for all that,’ finished Simmonds with conviction.

‘You can go,’ said Alan. Then he turned to Sophy, who was opening the envelope. ‘Let me read that letter first,’ he said.

‘Why, Alan? There is no need. It is only a begging letter. Come and read it with me.’

He gave way, and looked over her shoulder at the elaborate writing.

‘Miss’ (it began),

‘The undersigned, if handsomely remunerated, can give valuable information regarding the removal of the body of the late Richard Marlow from its dwelling in Heathton Churchyard. Verbum dat sapienti! Forward £100 to the undersigned at Dixon’s Rents, Lambeth, and the information will be forthcoming. If the minions of the law are invoked the undersigned with vanish, and his information lost.

‘Faithfully yours, Miss Sophia Marlow,

‘CICERO GRAMP.’

As she comprehended the meaning of this extraordinary letter, Sophy became paler and paler. The intelligence that her father’s body had been stolen was too much for her, and she fainted.

Thorold called loudly to Miss Vicky.

‘Look after her,’ he said, stuffing the letter into his pocket. ‘I shall be back soon.’

‘But what—what—?’ began Miss Vicky.

She spoke to thin air. Alan was running at top speed along the parade in search of the fat man.

But all search was vain. Cicero, the astute, had vanished.

CHAPTER IV (#u6c673537-f57b-564e-83f0-e505de336ec2)

ANOTHER SURPRISE

HEATHTON was only an hour’s run by rail from Bournemouth, so that it was easy enough to get back on the same evening. On his return from his futile search for Cicero, Alan determined to go at once to the Moat House. He found Sophy recovered from her faint, and on hearing of his decision, she insisted upon accompanying him. She had told Miss Vicky the contents of the mysterious letter, and that lady agreed that they should leave as soon as their boxes could be packed.

‘Don’t talk to me, Alan!’ cried Sophy, when her lover objected to this sudden move. ‘It would drive me mad to stay here doing nothing, with that on my mind.’

‘But, my dear girl, it may not be true.’

‘If it is not, why should that man have written? Did you see him?’

‘No. He has left the parade, and no one seems to know anything about him. It is quite likely that when he saw us returning to the hotel he cleared out. By this time I dare say he is on his way to London.’

‘Did you see the police?’ she asked anxiously.

‘No,’ said Alan, taking out the letter which had caused all this trouble; ‘it would not be wise. Remember what he says here: If the police are called in he will vanish, and we shall lose the information he seems willing to supply.’

‘I don’t think that, Mr Thorold,’ said Miss Vicky. ‘This man evidently wants money, and is willing to tell the truth for the matter of a hundred pounds.’

‘On account,’ remarked Thorold grimly; ‘as plain a case of blackmail as I ever heard of. Well, I suppose it is best to wait until we can communicate with this—what does he call himself?—Cicero Gramp, at Dixon’s Rents, Lambeth. He can be arrested there, if necessary. What I want to do now is to find out if his story is true. To do this I must go at once to Heathton, see the Rector, and get the coffin opened.’