По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

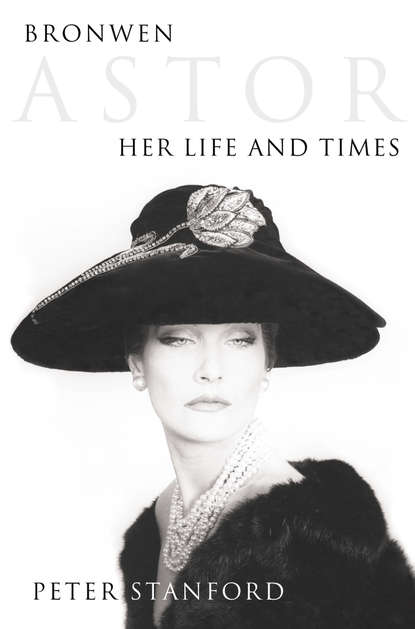

Bronwen Astor: Her Life and Times

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After her first brush with something ‘other’ at a seven-year-old’s birthday party, she continued in her school years occasionally to have experiences for which she could find no rational explanation. ‘As a teenager, I was having these extraordinary experiences of nature. I’d be on a walk with my school friends and quite suddenly there was no one there. It is like an explosion. And it left me with this wonderful feeling of being at one with everything. You’re not looking at the sunset, you’re part of it. Something clears in your mind and you understand something of the reality of nature.’ Had she then consulted the literature of Christian mysticism, she would have found parallel accounts of an overwhelming sense of oneness with the natural world and divined a clue as to what she herself in a small way was experiencing. Yet there was no one who could point her in the right direction and such exotic and generally Catholic spiritual raptures had no place in the conventionally Protestant and pointedly practical world of Dr Williams’. ‘I tried making a remark about it, wondering if the others I was with felt the same things, but no one said anything. Up to then I’d assumed everyone was the same. When I realised they weren’t, I felt very isolated.’

In July 1945 fifteen-year-old Bronwen Pugh went with a group of girl guides from Dr Williams’ to spend a week camping at Maidenhead next to the Thames in Berkshire. A mile or so up river at Cliveden, a wedding had just been celebrated. William Waldorf Astor, the thirty-eight-year-old eldest son and heir of the second Viscount Astor and his formidable MP wife Nancy, had married the Honourable Sarah Norton, twelve years his junior, daughter of the sixth Baron Grantley and a descendant of the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan. While the girl guides cooked beans over a camp fire and got up to schoolgirl pranks, ‘Bill’ Astor was away in the States introducing his new bride to his wealthy American relatives before returning to set up home near Oxford and pursue his own political career.

The gulf in age, class and experience between Bill Astor and Bronwen Pugh in 1945 could not have been greater. For her part, she did not even register from her campsite the existence of Cliveden, the stately home that fifteen years later was to become her home.

* (#ulink_18963ecf-1caa-5003-8c4b-1d1d26eb4ed9) She always used the Welsh form of ‘My father’ in letters.

Chapter Three (#ulink_277f4d2f-e4a6-5e98-85f8-04cb71124b6f)

It is vital to realise that we have come through difficult years and to get through them will require no less effort, no less unselfishness and no less work than was needed to bring us through the war.

Clement Attlee, broadcast (1945)

The Central School of Speech and Drama boasted an impressive London address – the Royal Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences on Kensington Gore. This circular, red-brick and terracotta landmark, with a capacity of 10,000, had since its opening in 1871 doubled as a giant concert hall and a conference centre. This dual purpose suited Central well, for the school not only had use of various conference rooms and a mini-theatre back stage but also had access to the main auditorium at various times during the day.

As a stage from which to learn voice projection, the vast arena was unparalleled. It was also, past pupils recall, a baptism of fire. The infamous Albert Hall echo thwarted many of their best efforts and was only cured much later in 1968, when the decorated calico ceiling was replaced by the giant suspended mushroom diffusers that still hover incongruously over the auditorium today.

Most of Central’s stage work, however, took place in a small theatre housed above one of the four great porticos that lead into the Albert Hall. There were other movement rooms and a lecture theatre, with the school’s canteen and additional teaching rooms housed down the road on Kensington High Street. Being part of the life of the Albert Hall had many fringe benefits for the students, not the least of which was the chance, outside hours (and occasionally, playing truant, when they should have been in lectures), to relax in the stalls and watch and learn as a procession of musical and theatrical stars rehearsed for their evening performances. When the habit became too popular and threatened to interrupt lessons, the principal, Gwynneth Thurburn, would send a note to the absentees in the stalls, telling them that any classes skipped would have to be made up out of hours. It usually prompted an exodus, for Miss Thurburn’s word went unchallenged at Central.

She had taken over in 1942 from the founder, Elsie Fogerty, and it was her dynamism during her long reign until 1967 which transformed Central into an internationally renowned drama school and ultimately saw it move away in 1957 from the Royal Albert Hall to bespoke premises in the old Embassy Theatre at Swiss Cottage. Admittance was by interview and audition with ‘Thurby’, as she was known to staff and pupils. She could appear very stern, recalls Margaret Braund, Bronwen’s drama teacher at Dr Williams’, a graduate of Central and later a tutor there, ‘but she was also very kind, very understanding and knew in a minute what students were or weren’t capable of achieving.’ As well as a stage course, Central also offered three-year diploma courses for speech and drama teachers and for speech therapists. Thurburn believed all three to be of equal merit. ‘There is something,’ she once wrote, ‘uniting everybody in this school – actors, teachers, speech therapists. For me it certainly is the voice, being the centre of all communication.’

Though the recommendation from Miss Braund may have helped Bronwen in her interview, she would not have got in unless Gwynneth Thurburn had spotted some talent in her. With hindsight, Margaret Braund believes it may have been Bronwen’s voice. ‘Her voice had a very pleasing quality, and it was very flexible. She had grown quickly into a good actress but it is her voice that stands out in my memory.’ All three courses at Central were officially on a par, but it was the actors’ diploma which carried most glamour. The eighteen-year-old Bronwen Pugh nursed ambitions to be on the stage, but she applied instead for the teachers’ course.

Part of it was a lack of confidence. She may have shone in the small pond of Dr Williams’ school productions, but was unsure how her credits from rural Wales would fare when placed alongside a string of leading roles in cosmopolitan youth theatres. Though physically now an adult, there was still a legacy of immaturity from her sheltered school years and her treatment as the baby of the family. And there was also a vulnerability about her that at this stage of her life was linked to that immaturity, but which remained ever after, even when she had learnt about the world in sometimes the cruellest ways. Fear of rejection, of being among people who do not want her there, has been one of the strong emotions in her life, a practical weakness set against and sometimes curtailing another of her enduring qualities, her willingness to strike out on bold, unexpected and often criticised paths with an unshakeable belief that she is somehow being guided from above on a predetermined spiritual journey.

Many of her rivals for one of the coveted places on the Central actors’ course, she believed, would have been living and breathing the dream of treading the boards from the cradle, while she had come late and not entirely wholeheartedly to the idea. It was for her less a vocation, more a cross between an alternative to Oxford, something to do, a gesture of defiance and a way to be different from her sisters. Moreover, she lacked the firm parental support that might have given her, at an impressionable age, the confidence to opt for acting. Alun Pugh, whom she looked up to above all others, who taught her that if you do anything you must be the best at it, may have agreed to pay the two pounds, six shillings per term, but there was little of the instinctive sympathy for his daughter’s choice that would have greeted a decision to apply to Oxford. He had his youngest daughter down to succeed as a headmistress, so the teachers’ course was at least a compromise between her option and his.

There was a further complicating factor – one that was to haunt Bronwen throughout her professional life. The Goodyear genes made for tall women and all the Pugh girls were giants. Gwyneth was just over six foot, her mother and two sisters just under. So Bronwen was deemed by the standards of the day too tall to be a successful actress. Even in later, more tolerant times tall actresses like Hollywood star Sigourney Weaver have struggled to find female leads (she was sidelined into science fiction), but back in the 1940s anyone over five foot six faced a bleak future. Leading men had to gaze masculinely down on their petite feminine charges – women like Celia Johnson, Olivia de Havilland and Audrey Hepburn. Actresses approaching six foot would find it impossible to persuade casting directors of their merits. Of Bronwen’s generation, only the well-connected and extraordinarily talented Vanessa Redgrave – for whom she was once mistaken while on a plane – became a star despite her height.

And the slight cast in her eye, corrected by surgery in childhood but set to return at various stages of her life, also counted against her in the theatrical world of the 1940s and 1950s. Though today actresses like Imogen Stubbs have won acclaim despite having a squint, four decades ago it was considered an insurmountable obstacle to success on the stage.

Bronwen was unusually realistic for an eighteen-year-old about her own talent – or lack of it. It was as if simply being at Central – rather than Oxford – was enough for her. ‘I think that great actresses succeed because they can let go of themselves and become totally someone else. I think that even at that stage I knew myself well enough to know that I couldn’t do that. Obviously later there was an element of letting go in being a model girl, but then it was not about taking on another character. It was simply letting go. I could go half the way, but I was too self-conscious to be an actress.’

Perhaps the final deciding factor was the encouragement of her mentor, Margaret Braund, who was also pushing her towards the teachers’ course. ‘It was not that I didn’t believe in her as an actress. It was rather that I knew she was an intelligent girl and one who would need academic stimulus. You got more of that in the third year of the teachers’ course. For the first two it was virtually the same as the stage course, but in the third year the teachers did subjects like psychology and phonetics. And I also thought that she would make a good teacher. She had imagination and ideas and she could inspire others if she wanted to. Though at this stage she was still quite young for her years, she was quite mature in her dealings with others.’

After decamping from Dolgellau a term early, she spent the spring and summer of 1948 in Hampstead – part of it acting as housekeeper to her father while her mother packed up their home in Norfolk. Alun Pugh and his youngest daughter also went off together for a motoring holiday in Europe. The stated reason was so that Bronwen could practise her skills as a driver there. She was at the wheel most of the time and although driving on the opposite side of the road might not be considered as the best preparation for the British test, she nevertheless passed with flying colours on her return. ‘We were always taught that getting your driving test was as important, if not more important, than getting your highers. It made you mobile and therefore independent. Being independent was the big thing.’

The real purpose of the trip to the continent, however, was to revisit some of the battlegrounds where Alun Pugh had served in the First World War. Father and daughter did not get as far as the trenches or the graveyards. When it came to that point, he couldn’t go on. ‘He wanted to try, but he couldn’t face it. He didn’t talk about it at all. I was just there.’ The silence that seemed to encase the details of her father’s wartime trauma persisted, but Bronwen became even more acutely aware of the pain it continued to cause him. Perhaps Alun Pugh chose his youngest daughter as his companion on this trip precisely because he knew that she – unlike her more assertive older sisters – would not press him to discuss topics that were difficult for him. She was content simply to let him be.

That summer between school and college Bronwen had her first romance. It was a short-lived, shared but unspoken passion, more an early and tentative stepping stone in her own emotional development than any significant pointer to her orientation. She fell for a girl of her own age, the daughter of Major-General Sir Francis Tuker, the Gurkha chief who had inspired her as a schoolgirl with his visits to Dr Williams’, his letters from the front and his tales of bravery. Joan Tuker, the same age as Bronwen, lived on the family farm in Cornwall and the two met up several times that summer. Undoubtedly some of the awe with which Bronwen regarded Sir Francis was transferred on to Joan. ‘I put her on a pedestal and just gazed adoringly at her. She had wonderful eyes and blonde hair. I think it was the first time I realised what romance was, that I began to understand how love could develop between two people, that I had had those feelings for anyone. It lasted six months and was reciprocated, but then I think we simply grew apart, me with my life in London and she down on the farm in Cornwall. We had nothing in common really.’

Joan was, like Bronwen, a third daughter and the two shared similar frustrations about how they were simply expected to be like their successful older sisters. Bronwen compares their friendship to that of Sebastian Flyte and Charles Ryder in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, a stage both were going through on the road to adulthood. ‘By the end, I knew I wasn’t a lesbian. If anything it was like a practice before I entered a world where there would be men of my own age.’ They lost touch but, soon after leaving Central, Bronwen heard that Joan Tuker had died tragically young of a brain tumour.

Bronwen started at Central in September 1948. For the first term all three groups – actors, teachers and therapists – had classes together. The focus was on the voice, under the guidance of Cicely Berry, later head of voice at the Royal Shakespeare Company. ‘They’d tell us to come in in trousers and we would He down on the floor and relax with lots of oohs and aahs,’ recalls fellow student Diana de Wilton, ‘and then the teacher would say something like, “Think of a sunny day in the country,” and we’d all have to concentrate our minds on our feet and then work our way slowly up to our necks.’ On another occasion they went off to visit the mortuary at the old Royal Free Hospital in Islington to inspect the lungs of dead bodies so as to understand how to breathe and project the voice.

There were twenty students on the teaching course. It was predominandy female, with just three men. Among the acting fraternity, the star of the year was the young Virginia McKenna, later to appear in Born Free and A Town like Alice. It was the slight, elegant, conventional McKenna who was regarded as the great beauty of the set. Although the intake in 1948 was unusual in including some older students – recently demobbed from the forces, their education delayed by the war – the atmosphere at Central was less like a modern-day university and more an extension of school. The timetable was rigid, free time scarce and a well-ordered, disciplined and slightly parsimonious feel pervaded the whole institution, radiating out from Gwynneth Thurburn’s office. ‘It was always vital,’ she recalled of this early period of her principalship, ‘that if we were to keep going, we should not waste a pennyworth of electricity or a piece of paper, a habit that has become ingrained in me. If we had not kept to Queen Victoria’s remark – “We are not interested in the possibility of defeat” – we should probably not be here today.’

The controlled environment of Central was then for many of its younger students a transition point between the childish world of school and adult society rather than a straight transfer. There were, of course, new departures from school life, among them famous names on the teaching staff. The playwright Christopher Fry was a tutor, as was Stephen Joseph, later to be immortalised when Alan Ayckbourn helped fund a theatre named after him in Scarborough. One of the most distinguished voice coaches at Central was the poet and essayist L. A. G. Strong, by chance an old school friend of Alun Pugh. He would take each of his pupils to lunch on nearby Kensington High Street each term. He regarded them as adults and treated them accordingly.

Yet the freedoms now associated with student life barely existed for Bronwen and her colleagues. In part it was the prevailing social mores of the time. After the wartime blip, these had settled down into more traditional patterns. More influential was the precarious economic state of Britain. It was a grey and serious world, with only Labour’s initial radical fervour for a centralised, managed economy to set people aglow. When that ran out, along in August 1947 with the American loans that had shored up the British economy, rationing bit ever harder, shop shelves were empty and pessimism set in. The great winter crisis of 1947 was the prelude to Bronwen’s arrival at Central. It was one of the coldest on record, and the mines could not supply the power stations so electricity rationing was instituted. There were fines for switching on a light outside prescribed hours. The lack of housing – some half a million homes had been destroyed during the aerial bombardment of Britain – loomed large in many lives, with endless waiting lists even for temporary ‘prefabs’. Many despaired of ever reaching the top and between 1946 and 1949 1.25 million Britons emigrated to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Southern Rhodesia.

Basic foodstuffs remained restricted until 1954 – one egg a week, three ounces of butter, one pound of meat. And clothes were bought by coupon until 1949. While Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’, launched in Paris in early 1947, captured the public imagination, its long skirts and flowing lines harking back to an earlier age of plenty, young women in Britain had to make do with dull and utilitarian garments purchased with coupons. Even Princess Elizabeth struggled to acquire the 300 coupons needed for the Norman Hartnell -wedding dress she wore when, on 20 November 1947, she married Philip Mountbatten in Westminster Abbey.

Bronwen, liberated at last from the green and blue ensemble of Dr Williams’, did not let the post-war restrictions constrain her from developing a style of her own. On a limited allowance from her father and faced by the absence of choice in shops, she turned to dress-making with the grey satin and pink lace she could scramble together. The boat neckline was in vogue, worn without sleeves. ‘It must have looked so drab, I’ve never had any idea about colours, but I thought it was the most marvellous thing in the world.’

In contrast to most, she was once again privileged – not only in her freedom to attend the decidedly un-utilitarian environment of a drama college, but also economically. The differentials that had been eroded in the Pughs’ life by war were restored. When she turned twenty-one in June 1951, her last month at Central, she received the then considerable sum of £1,000 as her part of her maternal grandfather’s will. It enabled her to buy her first car – a convertible Morris Eight – and later to move out into her own flat, a radical departure in the early 1950s for a young, attractive, unmarried woman of her class. Usually flying the nest only took place when the parental home was being exchanged for the marital one, but the Pughs, anxious as ever that their daughters should be independent, raised no objections. Bronwen may not have moved in the same world or same league as her contemporaries among the blue-blooded debutantes who were still being presented at court, but she led a cushioned, privileged and in many senses thoroughly modern life.

For her student days and beyond, though, Pilgrims Lane remained home. She would take the tube in each morning and return every evening. Relations with her mother, never close, became at least more relaxed. Kathleen Pugh had been appointed a magistrate on the local bench. Whatever frustrations she had felt in the pre-war years at her own lack of a career were thereby assuaged and she began to resent her youngest daughter a little less. Gwyneth, working as a journalist for a farming magazine after completing her degree at Oxford, continued to be close to Bronwen, but after a short career as a sub-editor, in 1949 Ann married Reginald Hibbert, her boyfriend from Oxford, and followed this bright, high-flying diplomat overseas on a Foreign Office career that culminated in his appointment as British ambassador in Paris in 1979 and a knighthood. constantly abroad, Ann was largely absent from her younger sister’s life in the decades ahead.

In 1950, when Bronwen was just twenty, tragedy struck when David Pugh died of cancer at the age of thirty-three. He had served in the ranks in Germany during the war, but as ever his record had disappointed his parents, who would have liked to see him an officer. His marriage – to a Welsh girl on St David’s Day 1943 – should have pleased his father. It was by all accounts a happy union, but again the Pughs harboured reservations, suspecting that Marion Pugh was chasing what she supposed to be her in-laws’ wealth. After his demobilisation, David Pugh was dogged by ill-health and in 1949 cancer was diagnosed in his groin. Further tests revealed that it had already spread all around his body and within a couple of months he was dead. ‘It shattered my parents,’ says Bronwen. ‘He had never been the son they wanted. He had an unusual mind. He had perfect recall, could remember telephone numbers, facts and figures, but he could never pass exams. He was weak, sickly and highly strung. When he died there was such remorse, especially when they realised the reasons for his illness.’

A post-mortem revealed that David Pugh had a small foetus inside his ribs. During her pregnancy Kathleen Pugh, doctors suggested, had originally been carrying twins, but the fertilised ovum had not divided into two as it usually does. Instead David had absorbed his twin. It is a very rare, but recognised medical condition, though usually it is discovered soon after the surviving twin is born.* (#ulink_b80b348c-12ea-51bb-8e1b-098df7b24f59) The Pughs believed that it could have explained David’s ill-health and physical weakness. It also cast an interesting psychological light on his insistence, even into his late teens, on having a place set at table for his imaginary friend ‘Fern’.

For Alun and Kathleen Pugh, the tragedy of their son’s premature death left a lasting scar. Ann Hibbert remains convinced that the grief her mother felt damaged her health and eventually contributed to the stroke she suffered many years later. For Bronwen, though, David’s death, while regretted and mourned, was something she could recover from. The age difference between them had meant that the two had never been close. However, the loss of her brother may have had one lasting effect on her life. Alun Pugh had made no secret of his ambitions for his children. His son had not satisfied him. His eldest daughter had chosen marriage and a supporting role over a career of her own. Gwyneth was happy taking a back seat. Bronwen’s natural ambition-apparent but carefully reined in as she went to Central – may have been sparked by the desire, in some way, to make good her beloved father’s disappointment.

Bronwen soon fell in with a crowd at Central. She made up a foursome with fellow students Diana de Wilton, Erica Pickard and Joan Murray. They were an oddly symmetrical quartet – two tall, two short, two fair, two dark. While they all came from middle-class backgrounds and shared a similar sense of humour and a youthful determination to be frivolous whatever the gloomy national outlook, the four had contrasting but complementary characters. Diana de Wilton was a reserved, unconfident, convent-educated Irish Catholic from Tunbridge Wells, brought up by adoptive parents, while Joan Murray, small, witty and outgoing, had a Scottish father and French Jewish mother. It was Erica Pickard, however, who was the pivot of the group. The other three all regarded her as their special friend. Bronwen Pugh, even as a student, still lived in the shadow of others – her sisters, the glamorous Virginia McKenna and, within her own circle, Erica.

In Erica – as with Joan Tuker – Bronwen was again drawn to the third of three daughters, though this time there was no hint of romance in their friendship. And like Bronwen, Erica was trying to break the family mould. Her two elder sisters had become doctors. She was determined not to follow in their footsteps. There was, friends remember, something compelling and unusual about Erica. For a start, her family lived in Geneva, where her father taught at the university. She had spent the war years in America and that experience also contributed to her standing out from her peers.

‘She arrived with this American preppy look,’ Diana de Wilton remembers, ‘skirts and jumpers and blouses with little collars. We were all still in twin set and pearls, though under Erica’s influence we soon changed. And she was freer in thought, much more adult. I’d been to a convent where there was no freedom of thought, but Erica would take me to Quaker meetings “to broaden my mind”. I used to worry that I was committing a sin.’ Erica also had a more mature attitude to men than her three friends – all of them straight out of protective all-girl schools. ‘She was freer in her thoughts about boys and sex and those things,’ says Diana de Wilton. ‘Not that any of us were in any way experienced, but she was just less buttoned up. We tried to follow her lead.’ While the other three all lived at home, Erica enjoyed the freedom of her own flat in Golders Green, shared with one of her sisters.

All four – with the possible exception of Erica Pickard – were naive and unworldly in their dealings with men. For Bronwen there would be great romantic crushes that faded before the man in question even realised she was interested. If he then made a move, she would already have passed on to another equally unrequited passion. Men, in general, were regarded as desirable but optional and often little more than a subject of amusement. Alun Pugh’s efforts to introduce his daughter to eminently suitable but sensible young barristers across the dining table at Pilgrims Lane therefore failed to move her. ‘They would always be saying, “Well, what about so-and-so, there’s nothing wrong with him?” One of their candidates became known to us all as “poor Smith” because he was always wanting to take me out and I wasn’t interested. It wasn’t that I didn’t want romance, but I had no wish for anything serious, let alone thoughts of marriage.’

Despite being a young eighteen in many ways, she had a clear and unfashionable view that life had to be about more than marriage and settling down. ‘We had men friends, but they were never intense partnerships at all. We’d often swap boyfriends between the four of us. And then we’d drop them really just because we felt like it. It was all very innocent and casual. We were far too inhibited for it to be anything more serious. There was no pill so you didn’t have sex. Nice girls like us didn’t do it for fear of what might happen. If you did then it would be the person you intended marrying and I wasn’t thinking about marriage at all.’ Only later did her father tell her that she had left a trail of broken hearts in the Inns of Court.

Outside hours, the four young women would head off to the coffee bars and salad counters that were just starting to open up in the capital. There they would bury their heads in fashion magazines, planning what dizzy dress-making heights they would aspire to over the weekend with whatever they could get on coupons, though Bronwen now recalls that she invariably looked tatty. In the evenings they frequented the West End theatres – half a crown in the gods and then a long walk home. Laurence Olivier was a particular favourite of all four, while the link with Christopher Fry through Central got them into the first night of his celebrated verse play Ring Round the Moon at the Globe in 1950.

Otherwise there were parties, though Bronwen was twenty before she stayed out all night – at a sleepover at Joan Murray’s. ‘My parents were never strict, but if I was going to be late I’d tell them where I was, whom I was with and when I would get back. I always made sure that I was there on time.’ She began smoking, more because it was the done thing than through any overwhelming addiction, and enjoyed the occasional drink, though seldom to excess. Though she had ambitions to be a free spirit and mould-breaker, the Pughs’ youngest daughter gave her parents few sleepless nights.

The four young friends would often congregate at Pilgrim’s Lane. On one occasion Alun Pugh took his youngest daughter and her friends to court for the day. ‘We had asked him something about the law,’ says Diana de Wilton, ‘and he had then decided we should see what goes on at first hand. He was a very kind man, and charming too, but he could still be a little bit frightening. I remember him asking me what books I liked to read. I was only nineteen and shy and said, “Rebecca”. “Oh,” he said, “can’t you think of anything better than that?” I felt so ashamed.’

The unspoken assumption all through the course at Central was that it would lead to a career in teaching. Towards the end of the final term there was a tour of Home Counties’ schools, with the students producing and performing Companion to a Lady, The Harlequinade and the obscure Second Shepherd’s Play. Bronwen’s role was mostly on the production side.

After passing her final examinations and getting her diploma in June 1951, she turned her mind to finding a job. A selection of vacancies was displayed on the school noticeboard and she got the first post she applied for – at Croft House School, Shillingstone, in Dorset. That enduring lack of planning again played a part in her life for, had she made any preliminary enquiries, she would have realised it was a place to be avoided. Croft House was an odd set-up, run in their home by an eccentric, elderly couple, the Torkingtons, known to their disgruntled staff (for reasons that are now obscure) as Caesar and Pop. Miss Pugh’s classroom was in a greenhouse.

The pupils were all girls and had originally come to Croft House to keep the Torkingtons’ own daughter company as she was educated at home. It had subsequently grown in size but lacked any strong guiding principle beyond keeping its young ladies occupied during the school term. It was certainly not an outstandingly academic environment. When any girl passed her school certificate, it was announced at assembly and everyone clapped in surprise and awe. Such an achievement was something out of the ordinary. More often than not, a pony club rosette was all a girl had to show for five years at Croft House.

To her surprise, Bronwen found she enjoyed teaching. Or she enjoyed working with individual pupils. In front of a class full of disgruntled and unmotivated girls, however, she soon realised that her father’s ambitions for her to be a headmistress were misplaced. ‘My classes ended up uproarious, with me laughing almost as much as the girls. Since as well as teaching drama and voice, I was also their form teacher, I was summoned by the owners and asked to explain my behaviour. They asked how I was going to punish my class. When I suggested one idea, they countered with another. On my plate at the next meal time was my notice.’

Bronwen had lasted a year, by which stage she had become one of the longest-serving teachers. The Torkingtons had a habit of falling out with their staff over money, discipline or their unorthodox but dogmatic approach. Throughout the year she had managed to keep one foot in Dorset and one back in London, shuttling between the two in her car. Though Joan Murray had married the future television and film director Christopher Morahan straight after leaving Central, Bronwen, Erica and Diana would head off in search of adventure.

Once they motored up to Oxford to visit Nigel Buxton, an undergraduate there who had previously been lodging at the house in Pilgrims Lane. Through Buxton, later a successful journalist and travel writer, they were able to taste a little of the Oxford social scene that Bronwen had rejected as part of her decision to go to Central. It led to invitations to summer balls next to the Cherwell and even to Bronwen making such good friends at Oxford that in the summer of 1952 she joined some of them for a holiday in Europe.

When he had been lodging at Pilgrims Lane, Buxton had caught Bronwen’s eye and she had developed quite a crush on him, but by the time she visited him at Oxford her romantic thoughts had, as ever and girlishly, moved on. He, however, was now keen on her, as he confided to Diana de Wilton, but the object of his ardour was now unobtainable. ‘It was typical of me at the time,’ Bronwen now says. ‘I was so very impatient.’

Bronwen spent the Christmas of 1951 in Geneva with the Pickards. She and Erica both admitted to each other that they were disappointed by teaching and feared that they had drifted, unthinkingly, into a career that held little enjoyment for them. So, together, they dreamt up a route to adventure. With their heads buried in fashion magazines, the solution was obvious – be a model girl. It is now a standard teenage fantasy, but in the early 1950s it was an ambitious plan because the status of the model girl was still somewhat dubious. When, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the first mannequins had appeared in Paris, they were little more than glorified shop girls. Certainly it was not a career any bourgeois family would consider suitable for its daughters. ‘At the beginning of the century,’ the designer Pierre Balmain wrote, ‘mannequins were not accepted in society … they were often girls of easy virtue who dined in private rooms at Maxim’s and were slow to take umbrage if followed in the Rue de la Paix.’

Later, however, in the early years of the twentieth century, the advent of the Gibson girls added a new veneer of respectability to the profession. Named after the society artist Charles Dana Gibson, these big-busted, pinch-waisted young women, all with classical hour-glass figures, first featured in his work and later achieved national celebrity as the epitome of feminine beauty. The original Gibson girl – and the artist’s wife – was Irene Langhorne, whose younger sister Nancy was Lady Astor and who therefore became Bronwen’s aunt by marriage. Through Gibson, Irene Langhorne turned the archetypal southern belle into the icon of young American women for almost two decades.