По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

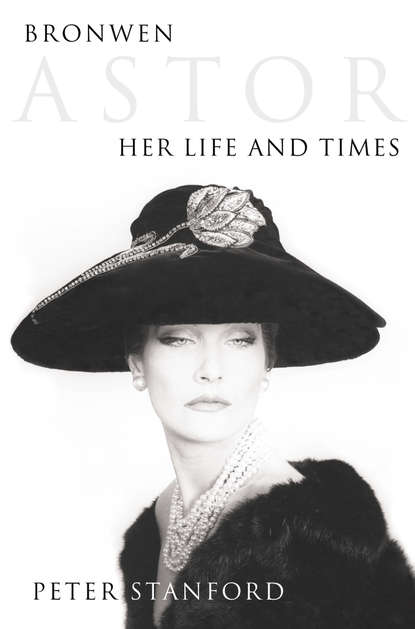

Bronwen Astor: Her Life and Times

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Until the Second World War a slightly seedy pall had continued to hang over the whole business of modelling, especially in Europe, with many of its practitioners rumoured also to be dispensing sexual favours. Only in the late forties and fifties did it become a desirable thing for a well-bred girl to do. This was first and foremost a commercial development. Those selling couture clothes realised that their customers were well-to-do and respectable women who would respond to seeing the garments they were about to purchase shown off by a young woman of the same class and background as themselves.

So Bronwen and Erica were among the first generation of young women able to read in fashion magazines of the glamorous but squeaky-clean lives of well-born and thoroughly upright models like British-born Jean Dawnay or the Americans Dorian Leigh and Suzy Parker, both immortalised by the celebrated fashion photographer Richard Avedon. These women were feted as stars and role models in the Hollywood mould. As Dawnay herself put it, in Paris in this period modelling ‘became an accepted profession, whereas before it was looked down upon as something into which men put their mistresses’. Dawnay, a household name in the early 1950s, set the seal on the new-found respectability of modelling when she married into the European aristocracy and became Princess George Galitzine.

In Erica Pickard’s case there was sufficient charisma and conventional good looks to make a career in modelling more than a pipe dream. ‘She had a lovely face, wonderful features and she was always slim,’ Bronwen remembers. ‘The only thing that marred her was her teeth. They crossed over slightly but we decided they could be sorted out.’ In Bronwen’s case, though, aspiring to be a model was a radical departure. She certainly had a theatrical side that liked performing, but only three years earlier she had lacked the confidence even to try for the actors’ course at Central. And up to this point there had been no hint that either she or anyone in her family regarded her as a great beauty.

Quite the opposite, her former nanny Bella Wells remembers. The orthodox line in the Pugh family remained that Ann was the beauty and Gwyneth the clever one, with Bronwen lost in a no man’s land between the two. Yet there was an obvious appeal in modelling for a young woman who had grown up feeling herself unwanted and who had therefore spent a good deal of energy in encouraging, cajoling and forcing her parents to ‘look at me’. This was attention-seeking turned into an adult profession.

Erica’s encouragement was crucial. According to Bronwen, ‘We never thought it would work, but we would look at the model girls in the magazines, look at ourselves and I would say, “You could do that,” to Erica, and then she would say to me, “And you could too.” It was a game, but slightly more than that – a challenge.’ Erica made Bronwen believe that her wild eyes and strong bone structure could be assets for a model girl, but the same problem that had blocked her path as an actress-her height-also made it seem unlikely that she would succeed in a world where short women were the most highly prized. (Dawnay, for example, was a petite, curvaceous blond.) And there was also the issue of her squint.

Diana de Wilton was another who could see beyond such eventually minor details to glimpse an unconventional beauty in Bronwen. De Wilton in particular was struck by her mannerisms. ‘She had this way of standing and walking. She had poise. When I look at our student photographs she had a way of placing her hands and turning her head that I now see made her a natural for modelling.’

Back in London after the Christmas break, Erica and Bronwen might well have forgotten their dream had they not read of a competition for budding model girls in Vogue. It was a diversion, but, bored by their everyday lives, they went at it wholeheartedly and had their portfolios made up by a high street photographer in Kensington. It was, they knew, a million-to-one shot, and their number did not come up. Modelling was put to one side and there it might have remained but for a tragic accident which changed the course of Bronwen’s life.

Soon after Easter 1952 Erica Pickard was standing on the open platform of a London bus when it swung round a corner. She was reaching over to press the stop bell and lost her grip. She fell out on to the pavement, cracking her skull against the curb as she tumbled. She was rushed to St Bartholomew’s Hospital in a coma. Her friends and family kept up a vigil at her bedside, but three days later she died at the age of just twenty-two.

‘It had a devastating effect on all of us,’ says Diana de Wilton. ‘I can only liken its effect on our group to the effect of Princess Diana’s death on the whole nation. We were used to older people dying, but when someone young, someone you know dies, then you realise your own mortality for the first time.’ For Bronwen it went further. It thrust her overnight into adulthood and precipitated a complete re-evaluation of her life and beliefs.

She was distraught. Of the four friends, she and Erica had grown the closest in the year after leaving Central. ‘I went to the funeral at Golden Green crematorium. When the coffin disappeared behind the screen, I heard this unearthly scream. It took a while for me to realise that it had come from me. I had to go back to school to teach straight away afterwards. One day, six weeks later, at tea I saw this piece of cake on my plate and couldn’t remember taking it. That’s when I realised I had been on auto-pilot. It was as if I had suddenly come round from concussion.’

Physically it may only have taken her six weeks to get over the shock, but the mental turmoil caused by Erica’s death was to remain with her for many years, pushing her ever more in on herself as she struggled to work out what the tragedy had meant. ‘I hadn’t realised that death could be so sudden. I’d lived through the war. I knew that people died. Yet Erica’s death changed everything.’

In coping with her grief, Bronwen turned naturally to the Pickard family. They clutched her to their bosom and tried to persuade her to take over Erica’s London flat in Golders Green and to apply for Erica’s job as a way of escaping the horrors of Dorset. She was reluctant, unwilling to step into the dead girl’s shoes at this vulnerable moment. She had fallen out with the Torkingtons and, if she was to stay in teaching, would need to start looking for another job. Yet she wasn’t sure teaching was for her. She liked one-to-one encounters but hated the classroom. And at least at Croft House School the timetable had been relaxed. Elsewhere the very sides of teaching she disliked the most – the discipline, the regimentation – would loom larger.

More broadly, Erica’s death focused her attention on the monotony of her day-to-day life. Was this how she wanted to spend her time here, however long or short? If she died tomorrow, would she feel fulfilled? Or was she in danger of falling in, after a brief period of rebellion, with the plan mapped out for her by her own family?

She knew she had to make a decision but was unsure which way to turn. The catalyst came from an unexpected quarter. She was invited to dinner by her old tutor from Central, L. A. G. Strong. ‘I said the usual thing, “Why this, why Erica, what now?” And he said, “Why did she choose you as her best friend?” And it was as if a light was turned on. As we talked I mentioned our idea of being model girls. I began to realise that one way to cope with Erica’s death was to follow that dream. She had given me the courage and confidence to try it, she had made me think it was possible. It wasn’t so much that over dinner I thought, “Oh yes, I can be a model girl”; it was that he set me thinking about what inner qualities she had recognised in me and what I should now do with them.’

Much later she was to realise that living out their daydream was a form of grief therapy, a way of blocking out the unanswerable questions that had suddenly descended on her after Erica’s death. Ultimately it was those questions that initiated Bronwen’s conscious spiritual journey, for the loss of her friend touched directly – as no event in her hitherto short life had – on the spiritual dimension that she had long been aware of, but which she had kept carefully hidden away and separated from her student friends and her family. ‘I think my father realised, though we never talked about it. And Gwyneth. But my mother and Ann had no inkling and even if they did, they would have had no sympathy.’ To this day Ann remains resolutely sceptical about Bronwen’s religious experiences.

Bronwen had taken tentative steps to reveal this inner dimension to her friends, knowing that she could no longer keep it bottled up. Leading a double life was, she came to see, unsatisfying. Some of her crowd had been unreceptive. Others had noticed but could not follow it up. Diana de Wilton, for instance, vaguely noted Bronwen’s tendency, whenever performing a passage for voice-training at Central, to choose something spiritual, like a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem. Yet she was never taken into Bronwen’s confidence.

On the surface there were few other clues. As a student Bronwen drifted away from any sort of formal church attendance. What she had experienced, she convinced herself, had little to do with organised religion. But with Erica it was different. ‘From the very start, all my insights into this parallel world had been about love – ‘Only love matters” is what I had heard that first time at the birthday party when I was seven. And it was so painful when Erica died, that I thought I had to stop loving. But equally I knew I couldn’t harden my heart. For a while I just shut down. That was my way of coping.’

And she might have remained ‘shut down’, closed to this other world, perhaps for ever, had not her meeting with L. A. G. Strong prompted her to follow her heart. Having a go at modelling became a small part of what was ultimately a wider liberation and discarding of conventional restraints that helped to form her later self. It was the outward sign that something had changed within her, but she did not know quite what for another eight years. Modelling gave her the space to find out.

Although hitherto she had had little inclination for books, after Erica’s death Bronwen became an uninhibited and often daring reader, working her way through a constant stream of sometimes enlightening and some disappointing texts – history, fiction, science, religion, psychology. Occasionally in the course of her life she has come across a book that has changed the way she thinks or opened up another perspective. Having, by her own choice, missed out on a university education, she has taught herself through books.

She was introduced to the writings of Georgei Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1874–1949) and his sometime disciple Peter Demianovitch Ouspensky (1879–1947). Both had died recently and she was directed to them, casually, by someone she met at a party. ‘You can imagine what I was like at parties then, very intense, always wanting to talk about ideas and only interested in people if they had something interesting to say.’

In the late 1940s and early 1950s among a younger generation of readers reacting, it has subsequently been suggested, to the recent world war with an abnormal degree of introspection and an over-eager and sometimes naive search for alternative paths, Gurdjieff and Ouspensky achieved the sort of cult status later enjoyed by Indian mystics in the sixties. They were, for Bronwen and many others in that period, a revelation and a first introduction to psychology.

Both were Russian, though Gurdjieff had Greek parents. Both were fascinated by the occult and experiments to prove that magic had an objective worth. But their enduring influence – certainly in Bronwen’s life – was their emphasis on the need for each individual to develop psychological insights in order to grow into a new state of higher consciousness. Such insights, she came to believe, could bridge the gap between her everyday world and the spiritual world she had glimpsed.

About Gurdjieff himself opinions were divided, even in his lifetime. His supporters – who included the New Zealand-born short-story writer, Katherine Mansfield – regarded him as a prophet and philosopher without equal. Kenneth Walker, a writer who was one of many who were drawn to the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Fontainbleau, described its leader as ‘the arch disturber of self-complacency’, but the press at the time and historians subsequently have judged Gurdjieff less kindly. R. B. Woodings, the distinguished chronicler of twentieth-century thought, sums him up thus: ‘His ideas are not original, his sources can be readily traced and the movement he stimulated was obviously part of reawakening of interest in the occult in the earlier part of this century.’ However, Woodings is in no doubt about the impact of Gurdjieff. ‘Whether charlatan, mystic, scoundrel or “master”, he exercised remarkable authority charismatically over his disciples and by reputation over much wider American and European circles.’

Ouspensky – for nine years until 1924 Gurdjieff’s self-appointed ‘aposde’ – was no less popular and now enjoys a little more academic credibility. Again he inspired a cult-like following, based on his estate at Virginia Water in Surrey, but he had a sounder grasp of philosophy than Gurdjieff and had studied both mathematics and Nietzsche before dabbling in the occult and theosophy, the belief system promoted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century by his fellow Russian Helena Blavatsky and her American associate, Henry Steele Olcott, which embraced Hindu ideas of karma and reincarnation.

And it was Ouspensky who made the greater impact on Bronwen. His The Fourth Way, published soon after his death in 1947, brought together many of the ideas he had relentlessly explored in his lifetime. It introduced Bronwen to eastern thought, which she found considerably more attractive than Christianity, and it described in detail his ‘system’ for greater self-knowledge and enlightenment. ‘The chief idea of this system,’ he wrote, ‘was that we do not use even a small part of our powers and forces. We have in us, a very big and very fine organisation, only we do not know how to use it.’ The idea, then, was to study oneself, following Ouspensky’s guidance.

This ranged from the mundane to the enlightening to the foolish. ‘We are divided,’ he claimed, ‘into hundreds and thousands of different “I”s. At one moment when I say “I”, one part of me is speaking, at another moment when I say “I” it is quite another “I” speaking. We do not know that we have not one “I”, but many different “I”s connected with our feelings and desires and have no controlling “I”. These “I”s change all the time; one suppresses another, one replaces another, and all this struggle makes up our inner life.’

To a young, impressionable woman who felt herself torn between the material and spiritual parts of her life, such ideas appeared attractive. She had already realised that she had two apparently contradictory impulses pushing her forward. One was the outgoing, fun-loving, meet-any-challenge, sporty side that was now drawing her to modelling. The other – a legacy, she was sure, from her Welsh ancestors – was driven by a solitary, contemplative, inward-looking instinct that made her want to run away from the world, curl up in a ball and search through books and thought for an answer to why Erica had died in such a tragic way. Ouspensky helped her at least to recognise these two faces within herself and gave her clues as to their origins.

When later he talked about the ‘negative emotions’ bequeathed by childhood and parents and the need to confront these in order to move to a higher level of consciousness, Ouspensky was speaking directly to Bronwen’s own experience, but it would be a mistake to imagine that she became any sort of convert to his cult. She was enthusiastic about her introduction to psychology and to discussions of levels of consciousness – Ouspensky declared there were four – and she was heartened to know that others too were struggling with the sort of questions she had hitherto tackled in secret and largely alone, but Ouspensky was simply a starting point.

In the light of her subsequent determination to combine psychological insights with organised religion – though of course at this time she was a lapsed Anglican – Ouspensky’s antipathy to belief should be noted. Despite borrowing from eastern and western religious creeds, Ouspensky boasted that his system ‘teaches people to believe in absolutely nothing. You must verify everything that you see, hear or feel.’ And some of the conclusions to which he took initially attractive ideas appeared ridiculous, even to one as inexperienced and naive as Bronwen at that stage. His theories about the effect of earthly vibrations on the mind and his peculiar mathematical tangle, ‘the ray of Creation’, ascribing numerically quantified ‘forces’ to a series of worlds (which themselves were listed from one to ninety-six) must have been difficult for even the most avid follower to swallow.

Yet Ouspensky and Gurdjieff initiated a search for a complementary psychological and spiritual framework that has since dominated Bronwen’s life. In her student days and as she took her first faltering steps into the adult world of work, the two principal elements within her and hence in her story began to unravel – the spiritual and the material. At the same time as she was setting her sights on the flimsy, fun and throwaway world of model girls, with their jetset lifestyles, headline-grabbing antics and aristocratic suitors, she embarked on a lonely and often painful journey to understand her own psyche and soul.

* (#ulink_9c82eef9-d487-519b-8da3-ad53f8799bb7) In a recent similar case in Egypt, reported in British medical journals, a sixteen-year-old builder went to see his doctor with severe stomach pains. An X-ray revealed a swollen sac pressing against his kidneys and containing his unborn twin, a seven-inch long foetus, weighing more than four pounds. It had a head, an arm, a tongue and teeth. Like an incubus it had been surviving inside the sixteen-year-old, feeding off him.

Chapter Four (#ulink_4c13623a-2a64-53c0-baa0-b93e93f98d4c)

One of the many reasons why it is difficult to make a start as a model is that, although the photographers and fashion houses are crying out for new faces, when it comes to the point none of them want to take the risk of trying out a new girl while she is still green.

Jean Dawnay, Model Girl (1956)

The fashion world recovered more quickly than most industries from the dislocation of the war. In Paris in February 1947 Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ thrilled critics, buyers and public alike. ‘It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian,’ remarked Carmel Snow, reporting for Harper’s Bazaar, at the unveiling of Dior’s dramatic, narrow-waisted, low-cut, very feminine and distinctly nostalgic collection, harking back, some experts said, to the hour-glass silhouette of the 1890s. ‘Your dresses have such a new look. They’re quite wonderful.’

Snow had coined a phrase to emphasise Dior’s break with the drab, austere and utilitarian style of the war years, symbolised by his abundant use of material after a period in which it had been severely rationed. Dior, Snow claimed with some truth, had done more, however, than simply create a style. ‘He has saved Paris as Paris was saved in the Battle of the Marne.’

For there had been doubts expressed about the French capital’s ability to regain its pre-war dominance of the fashion industry, notably with American buyers. Certainly during the war years Paris had lost its crown when Hollywood brought together fashion and film to make New York’s Seventh Avenue the place to be, but the transatlantic clamour that followed the launch of the New Look – Olivia de Havilland and Rita Hayworth were amongst the Hollywood stars who rushed to place orders – ensured that Paris was back at the top of the tree. Pierre Balmain, Jacques Fath and Cristobal Balenciaga all contributed to this pre-eminence; by 1950 they had been joined by Pierre Cardin, two years later by Hubert de Givenchy. But it was Dior who reigned supreme.

In so far as Paris entertained any European rivals, they were Rome and Florence, where designers like Capucci, Pucci, Simonetta, Fabiani and Galitzine were admired, if not held in quite such global high esteem as Dior and his near neighbours. In the fashion industry, London remained something of an enigma. It considered itself as good as, if not better than, Paris and certainly looked down on the Italians. Throughout the 1950s the universal penchant amongst Europe’s designers for classically English tailored evening dresses and tweed suits as part of an exaggeratedly aristocratic look contributed to London’s self-assuredness. But the irony was that the driving force behind this English look was Paris, which took the safe lines coming out of London – ‘knights’ wives clothes’, as they were sometimes unkindly labelled – and turned them into something special.

The traffic was, in reality, two-way. London had been touched by the shock waves that issued forth from Paris with the New Look. Like the rest of the fashion world, it followed Dior’s lead. Yet it did so in moderation, sticking to its own particular style and developing its own innovations – like coloured furs. Jean Dawnay, who worked with the top designers on both sides of the English Channel before she retired as a model girl in 1956, sums up the subleties of the battle with an anecdote. While working at Dior, she was sent as one of a small team to show some of the house’s latest designs at the French embassy in London. The clothes had a strongly English look. To acknowledge his design debt to his hosts, Dior decided that his designs should be made up in British tweeds and worsteds. According to Dawnay, the gesture backfired when the flowing dresses she had worn in Paris overnight became stiff and ungainly when made from home-spun cloth. They did not move with her body but stood out in counterpoint to it. Only the most formal suits and evening dresses translated well. ‘The English designers catered almost exclusively for the smart English families,’ says Dawnay. ‘If they were having a ball or a coming-out party, they would go to Hardy Amies for a dress and so on. It was very insular, had its own standards and was rather dismissive of anywhere else.’

The global commercial reality, as Bronwen Pugh embarked on her career as a model girl in 1952, was that London, for all its pride and introspective one-upmanship, remained very much a stopping-off point for American buyers on their way to the main market, Paris. It wasn’t until several years later that Mary Quant and Alexander Plunket Greene launched their Bazaar shop on Chelsea’s King’s Road and revolutionised London’s standing. As yet their particular new look was nothing more than the dream of fashion college students.

For a decade and a half after the war the London market was dominated by twelve names who joined forces in the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers. Worth, Norman Hartnell, Charles Creed, Neil ‘Bunny’ Roger, John Cavanagh, Digby Morton, Ronald Patterson and Hardy Amies were among the best – known stars in this galaxy, each putting on two shows a year – in January and July – where they unveiled their couture collections. Below them was a layer of younger designers, the Model House Group, who made their living by adapting last year’s couture house creations from Paris. And then there were the ready-to-wear houses, from smart names like Jaeger through to high street chains like Richards Shops. The days of the big names doing anything other than making individual items to order for a wealthy, predominantly older clientele had not yet dawned.

The timeless, upper-crust English quality of the designs of Amies or Hartnell, their appeal for a female audience looking for sensible suits for a weekend’s shooting in the country or a frock for a presentation at court, chimed well with the era. After the grey years of Labour centralisation of the economy, the election of a Conservative government in 1951 heralded both an end to rationing and a welcome return to some of the pleasures of pre-war days. London was loosening up. Taking their lead from the young Queen Elizabeth II on her accession in 1952, women who followed fashion aspired to a classical simplicity that mirrored the dress codes of the landed classes at play.

This was what the satirist and social historian Christopher Booker has described as ‘the strange Conservative interlude of the fifties’:

By the summer of 1953, the glittering coronation of a new young queen, marked in a suitably imperial gesture by the conquest of Everest, was a symbol that during the years of hardship the old traditions had been merely sleeping. People were once again dressing for dinner and for Ascot … Debutantes once again danced away June nights on the river, to the strains of Tommy Kinsman and the splash of champagne bottles thrown by their braying escorts. Unmistakably British society seemed to be returning from a long dark night to sunnier and more normal times.

It was a time when government and electors alike convinced themselves that Britain was back where it had been in 1939. ‘It’s just like pre-war’ was the phrase on everyone’s lips – before Suez, economic reverses, angry young men, the Lady Chatterley trial and finally the Profumo scandal destroyed the illusion and ushered in the new, brutal and classless world of the 1960s. In this interval a particular sort of upper-class conduct, confidence and style were the dominating social and cultural goals. Harold Macmillan’s governments, containing such a heavy contingent of peers that on paper they seemed like pre-1914 administrations, contributed to the process. The look that Bronwen Pugh came to embody – aristocratic, detached, elegant – reflected the general mood and had an emblematic quality.

The London fashion world did have one up on Paris in that it had adopted the American system of agents for model girls. In the States Eileen Ford, the godmother of model agents, had built up her agency from scratch in 1946, representing two of the most important US models of the decade, Suzy Parker and Dorian Leigh. In Paris such innovations were not allowed for fear that they would become little more than glorified escort agencies, but in London they advertised in the phone book and were run by outwardly frightening but often benign men and women who provided the respectability and parental-style security that ushered middle-class girls like first Jean Dawnay and later Bronwen into the profession.

With her teaching career behind her and her heart set on fulfilling the frivolous dream she had shared with Erica, Bronwen went about getting herself on one of the agency’s books. The first name she tried was Pat Larthe. Dawnay, trail-blazer in the new wave of post-war British models, provided an uncomfortable picture in her autobiography of Larthe’s working methods. At the dawn of her career, Dawnay, like Bronwen almost a decade after her, had nervously presented herself at Larthe’s office in London’s Covent Garden only to find ten other hopefuls in the waiting room, clutching their portfolios and fiddling with their hair.

When she was finally summoned into the inner sanctum she was greeted by a tough, theatrical woman, sheltering behind a vast telephone-laden desk. ‘The interview was short and humiliating. I showed Miss Larthe my pictures. She barely seemed to glance at them before telling me I was too ordinary, that modelling was the toughest, most soul-destroying profession in the world, and that girls who had far more than I in the way of looks and figure got nowhere.’ Dawnay was reduced to tears. That appeared to be Larthe’s intention, perhaps – to take the most charitable option – calculating that it was better if it was done by her now rather than by someone else further down the line. Having destroyed the younger woman’s self-confidence, she could then appear her protector. She took Dawnay under her wing, directed her first to favoured photographers, then got her bookings at the less glamorous end of the market – shows at Scarborough hotels – and finally helped her to make the leap to the top London houses.

Bronwen’s first impression of Larthe was equally unfavourable. ‘I just turned up in her office and said, “I want to be a model.” She looked at me and said bluntly, “You’re too tall and you squint.’” Most hopefuls would have turned and walked out. A few months previously so would Bronwen, but in the aftermath of Erica’s death she clung to the idea of modelling as her salvation. She could not afford such dramatic gestures when Larthe potentially held the key to success. ‘Then Pat asked me to walk across the room and I must have done something right. She said she wouldn’t put me on her books, but she’d teach me how to be a model.’

Bronwen accepted this less-than-overwhelming offer without a second thought. She and another hopeful would turn up after hours at Larthe’s office every evening for a week. First they were instructed on walking in the correct way. You had to place one foot exactly in front of the other and swing your hips – ‘but not all that sashaying they do today,’ says Bronwen. ‘We had to be “ladylike but exaggerated”.’ Then there was some good old-fashioned practice with books on the head to improve balance and poise.