По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

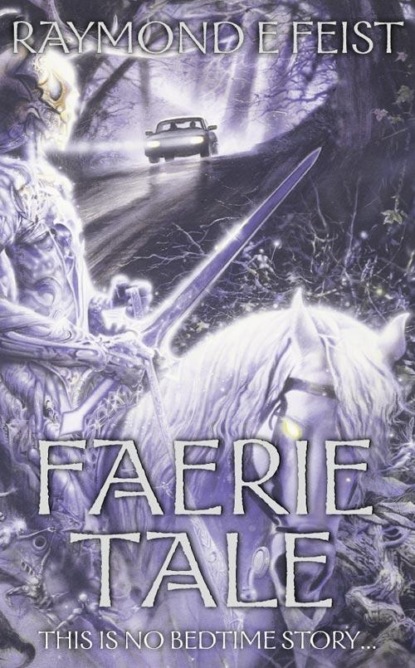

Faerie Tale

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It always is.’

Jack laughed at the remark. ‘I say the same thing when I’m trying to organize her papers.’

‘This boy is almost as big an oaf as you were, which means he’s a slightly better graduate assistant.’ Phil seemed unconcerned with the comparison. ‘Though, of my students, you have done better than most. I am glad you’ve returned to books. Those films were less than art.’

Talk turned to the differences between screenplays and novels, and they settled in for a while, enjoying the rediscovered friendship between Agatha and Phil, and the new friendship between Jack and Gabbie. Gloria remained distant, observing her husband. Phil responded to Aggie’s questions, and in a way her prodding produced more revelations about his work in minutes than Gloria had managed to extract in weeks. Not sure of her own reaction, Gloria settled in, considering.

She regretted Phil hadn’t volunteered as much to her as to Aggie, but then Aggie was a special person to him. After his parents had died in a car crash, Phil had been raised by his aunt Jane Hastings. But Aggie Grant, Jane’s best friend from college, and her husband, Henry, had been frequent visitors. When Phil had graduated from the University of Buffalo he had gone to Cornell to study with Aggie. And Aggie had secured the fellowship that had allowed Phil to attend the university. Gloria conceded that Aggie had been the single biggest influence in Phil’s career. She had been a courtesy aunt, but, more than family, she was his mentor, then his graduate adviser, and remained the one person he held in unswerving professional regard. Gloria had read two of Agatha’s books on literary criticism, and they had been a revelation. The woman’s mind was a wonder, with her ability almost to intuit the author’s thought processes at the time of writing from the finished work. She had never gained wide recognition outside of academia and she had her critics, but even the most vociferous conceded that her opinions were worthy of consideration. Somehow Aggie Grant posited theories about dead authors that just felt right. Still, in the field of literature, Gloria was simply a reader, not a critic, and some of what had been covered in Aggie’s books seemed rites reserved for the initiates of the inner temple. No, if Agatha could get Phil talking about his work, and his problems, Gloria was thankful. Still, she felt a little left out.

Suddenly Agatha was addressing her. ‘And what do you think of all this?’

Gloria improvised, her actress’s training coming to the fore. Somehow she didn’t wish it known she had been musing, not following the conversation. ‘The work? Or the move?’

Agatha regarded her with a penetrating look, then smiled. ‘I meant the move. It must be something of a change for you, after Hollywood and all.’

‘Well, the East isn’t new to me. I’m a California girl, but I lived in New York City for several years while I worked in theatre. Still, this is my first stint as a farmer’s wife.’

‘Hardly a farmer’s wife, my dear. Herman Kessler kept only enough livestock to qualify for federal tax exemptions: a dozen sheep and lots of ducks and chickens. That farm has never been worked. Herman’s father, Fredrick Kessler, never allowed it, nor did Herman. The meadows have not known the plough or the woodlands the axe for over a century. And this area was never as heavily harvested as others nearby to begin with. The woods behind your home may not be the forest primeval, but they are some of the densest in ten thousand square miles, perhaps the only such parcel of uncleared lowland woods in the entire state of New York.’

Phil said, ‘I was meaning to ask you: when we were at Cornell you were firmly established up in Ithaca. Now you show up in my old hometown. Why?’

She rose and went over to a sliding door. ‘A moment.’ She moved the door aside and vanished from view, reappearing almost immediately with a large blue three-ring binder. She returned to the couch and handed the binder to Phil as she sat down.

He opened it and read the first page. ‘“On the Migration of Irish Folk Myth and Legend to America in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. A critical study by Agatha Grant.”’ He closed it. ‘I thought you’d retired.’

‘I’m retired, not dead. This has been a hobby piece of mine for more years than I can recall.’ She seemed to consider. ‘I began it shortly after my Henry died. I was working on it when I was your adviser; I just never told you about it. Aarne and Thompson did some fine classification that came out in 1961. What I’m doing is using their motif index in following up on the work of Reidar Christiansen. He compared and studied Scandinavian and Irish folklore. I’m trying to do something like that with the older Celtic myths and the Irish folktales which have come to America.’

She addressed Gloria and Gabbie as well as Phil. ‘When I was a girl growing up at East Hampton, we had a lovely governess, an Irish woman named Colleen O’Mara. Miss O’Mara would tell my brother and me the most wonderful tales of elves and faeries, leprechauns and brownies. All my life I’ve been fascinated by folk myth. My formal education was in classics and contemporary literature, but I read Yeats’s faerie tales as readily as his poetry – perhaps with more enthusiasm. In any event, that is my work now. There were many immigrations from Ireland – besides the famous “potato famine” one – and thousands of poor, rural Irish came to America. Now, most of those who came settled in the big cities or went west to work the railroads. But Pittsville was one of the few rural communities to capture several waves of these Irish immigrants, many of whom remained farmers. This area is almost a “little Ireland”. I’m no stranger to the area, having visited my darling Jane many times over the years.’ She shared a fond look with Phil at the mention of his late aunt. ‘When I was offered the chair at Fredonia, I didn’t pause a moment in deciding where to live. I like Pittsville. We’re only a half-hour from the campus here. And there were unexpected bonuses.’

Phil showed he didn’t understand, and Jack offered, ‘Mark Blackman lives nearby.’ He pointed absently towards the west.

‘The occult guy?’ asked Phil, with obvious interest.

Jack said, ‘That’s him.’

‘Who’s Blackman?’ asked Gabbie.

Jack said, ‘Blackman’s a writer, a scholar, a bit of everything. He’s something of a character and pretty controversial. He’s written a lot of odd books about magic and the occult that have got the academic community upset. And he’s Aggie’s favourite debating opponent.’

Agatha said, ‘Mark Blackman’s a bit of a rogue in research and full of indefensible opinions, but he’s absolutely charming. You’ll meet him shortly. He’ll join us for dinner.’

‘Wonderful,’ said Phil.

‘He’s also a fund of information on just the sort of things I’m digging into,’ said Agatha. ‘In his library he has some very rare books – a first edition of Thomas Croften Croker’s Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, if you can believe it – and an amazing number of personal journals and diaries. His help has been invaluable.’

‘What is Blackman doing in Pittsville?’

‘You can ask him. I’ve got nothing like a reasonable answer, though he’s very amusing in his avoidance. He has ventured he is working on a new book, though the subject matter is unknown to me. That is all.’ Agatha paused as she considered. ‘I find the man fascinating, but also a little irritating with his secrecy.’

Phil laughed. ‘Agatha believes in spreading ideas around.’ He made the remark to the others over Agatha’s protests. ‘When I began writing fiction on the side, as a grad student, she couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t show it to her until it was done.’

To Gabbie, Agatha said, ‘Child, your father doesn’t write. He brews magic in a cave and woe unto him who breaks the spell before it’s done.’

Phil joined in the general laughter, and the talk turned to old friends and colleagues from their days together at Cornell.

• Chapter Ten • (#ulink_99efd886-600e-56d9-824f-47aec7adceec)

Patrick and Sean hovered over the box in the barn. The cat regarded the boys with indifference as they petted and played with her kittens. Her babies were at that awkward stage just after their eyes had opened, their clumsy antics provoking laughter from the boys.

Patrick picked up a kitten, who mewed slightly. He petted it and said, ‘Pretty neat, huh?’

Sean nodded as he reached out and stroked another. A scurrying in the hay near the darkest corner of the barn caught his attention. ‘What’s that?’

‘What?’

‘Over there – something moving in the hay.’ He pointed. Patrick put down the kitten and rose. He walked purposefully towards the dark corner as Sean said, ‘Don’t!’

Patrick hesitated and turned to face his brother. ‘Why?’ he demanded.

Sean reluctantly came over to stand by his brother. ‘Maybe it’s a rat or something.’

‘Oh brother!’ said Patrick. ‘You’re such a baby.’ He glanced round and saw an old rusty pitchfork by the door. He fetched it from the wall, barely able to balance the long tool. Slowly he moved towards the corner and began poking at the old straw. For a long moment there was no hint that anything but straw rested beneath the rusty tines Patrick waved before him. Gingerly he poked the fork deeper into the straw, moving it aside.

Then something appeared from under the straw. It stood less than two feet tall, regarding the boys with large, blinking eyes. It was a little man. From head to foot it was dressed in odd-looking garments: a tall hat, a green coat, tightly cut breeches, and shoes with tiny golden buckles.

The boys stood motionless, as if unable even to breathe. The little man tipped his hat and, with a wild, piercing laugh, leaped from the straw, jumping high between the boys and landing at a scampering run across the barn floor. Patrick echoed Sean’s yelp of fright as he dropped the pitchfork and spun around, his eyes never leaving the diminutive creature who leaped high up on the opposite wall, vanishing through a crack between loose boards.

The boys stood silently rooted, their eyes wide with wonder as they attempted to sort out the flashing kaleidoscope of images they had witnessed. Both were shaking, terrified by the vision. Slowly they turned to face one another and each saw mirrored in his twin his own fright. Wide blue eyes, frozen smiles, and rigid posture suddenly gave way to motion as they dashed for the door.

They sped outside, looking back into the barn. Then a shadow loomed before them and they were enfolded in a pair of powerful arms. The boys shrieked in terror as they were tightly held. An odd odour stung their noses and a deep, scratchy voice rumbled, ‘Here, then! What’s it all about, lads?’

The boys were let go and retreated a step; they saw the shadow take shape in the form of an old man. He was broad of shoulder and tall, his grey hair unkempt and his unshaven face seamed and leathery. Red-shot eyes regarded them, but he was smiling in a friendly way.

Patrick’s heart slowed its thundering beat and he cast a glance at Sean. A thought passed between them, for they recognized the odour that hovered about the man like a musky nimbus. The man smelled of whisky.

‘Easy, then, what is it?’

‘Something back there,’ ventured Patrick, pointing at the barn. ‘In the hay.’

The man passed the boys into the barn, then waited while they indicated the corner. He walked purposefully to where the pitchfork lay and made a display of poking about in the straw. ‘It’s gone now,’ said Sean. The man knelt and moved some straw about, then stood and used the fork to put the straw back in a semblance of order. He turned a smiling, good-humoured face towards the boys. ‘What was it, then? A barn rat?’

Patrick glanced at Sean and gave him an almost imperceptible head shake, warning him to say nothing. ‘Maybe,’ said Patrick. ‘But it was pretty big.’ His voice was strident, and he fought to regain control of himself.

The man turned where he stood, looking down on the earnest little faces. ‘Big you say? Well, if there were chickens or ducks here, which there aren’t, and if it were night, which it isn’t, I’d suspect a weasel or fox. Whatever it was, it’s vanished like yesterday’s promises.’ The man returned the pitchfork to its place on the wall. He looked hard at the boys. ‘Now, lads, which one of you wants to be the first to tell me just what you saw?’

Patrick remained silent, but Sean finally said, ‘It was big and it had teeth.’ His voice still shook, so he sounded convincing.

Instantly the man’s expression changed. In two strides he stood before them, hands upon knees as he lowered his face to the boys’ level. ‘How big?’