По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

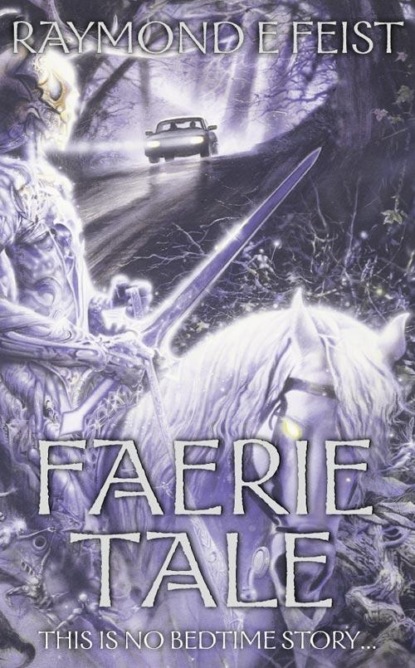

Faerie Tale

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Gabbie shook her head as she spurred her mount forward. ‘Nope, cowgirl. I’ve ridden English before. It’s just been a long time.’ She waved at her foot. ‘Acme cowboy boots. I’ll pick up some proper breeches and high top boots in town. My knees will be a little bruised tomorrow, is all.’

They rode out towards the woods, Gabbie letting Jack take the lead. ‘Watch out for low branches,’ he said over his shoulder. ‘These paths aren’t cleared like riding trails.’

She nodded and studied his face as he turned back towards the path. She smiled to herself at the way his back moved as he reined his horse. Definitely a fox, she thought to herself, then wondered if there was a girlfriend back at the college.

The trail widened and she moved up beside him, saying ‘These woods are pretty. I’m more used to the hills around the Valley.’

‘Valley?’

‘San Fernando Valley.’ She made a face. ‘Ya know, fer sher, like a Valley girl, totally tubular, man. I mean, like bitchin’, barf out, and all that shit.’ She looked irritated at the notion. ‘I grew up in Arizona. That image grosses me out.’ Suddenly she laughed at the slip and was joined by Jack. ‘LA’s just reclaimed desert. Turn off the garden hose and all the green goes away. It’s all chaparral – scrub, you know – on the hills north of the valley. Some stands of trees around streams. A lot of eucalyptus – nothing like these woods. It’s mostly hot and dry, and real dusty. But I’m used to it.’

He smiled, and she decided she liked the way his mouth turned up. ‘I’ve never been west of the Mississippi, myself. Thought I’d get out to Los Angeles once a few years back, but I broke my leg sailing and that shot the whole summer.’

‘How’d you manage that?’

‘Fell off the boat and hit a patch of hard water.’

For a moment she paused in consideration, for he had answered with a straight face, then she groaned. ‘You bullshitter. You’re as bad as my dad.’

‘I take that as a compliment,’ he answered with a grin. ‘Actually, some fool who thought he could sail put the boat around in a gybe without warning any of us, and I caught the boom and got knocked overboard. Smashed my leg all up. I spent the next day and a half with a paddle for a splint while we headed back to Tampa. Spent nine weeks in a cast, then six more in a walking cast. The surgeon was great, but my leg’s not a hundred per cent. When it gets cold, I limp a little. And I can’t run worth spit. So I walk a lot.’

They rode in silence for a while, enjoying the warm spring day in the woods. Suddenly there was an awkward moment, as each waited for the other to speak. At last Jack said, ‘What are you studying?’

Gabbie shrugged. ‘I haven’t decided. I’m only a few units into my sophomore year, really. I’m sort of hung up between psychology and lit.’

‘I don’t know much about psych.’ She looked at him quizzically. ‘I mean, what you would do when you graduated. But either means grad school if you want to use them.’

She shrugged again. ‘Like I said, I’m barely a sophomore. I’ve got a while.’ She was quiet for a long time, then blurted, ‘What I’d like to do is write.’

He nodded. ‘Considering your parents, that’s not surprising.’

What was surprising, thought Gabbie, was that she had said that. She had never told anyone, not even Jill Moran, her best friend. ‘That’s the trouble, I guess. Everyone will expect it to be brilliant. What if it’s no good?’

Jack looked at her with a serious expression on his face. ‘Then it’ll be no good.’

She reined in, trying to read his mood. He looked away, thoughtfully, his profile lit from behind by the sun shining through the trees. ‘I tried to write for a long time before I gave up. A historical novel, Durham County. About my neck of the woods at the turn of the century. There were pans of it that I thought were fine.’ He paused. ‘It was pretty awful. It was difficult admitting it at the end, because enough of my friends kept encouraging me that I thought it was good for a long time. I don’t know. You just have to do it, I guess.’

She sighed as she patted the horse’s neck. Her dark hair fell down, hiding her face, as she said, ‘Still, you don’t have two writers for parents. My mother’s won a Pulitzer and my father was nominated for an Oscar. All I’ve managed is some dumb poetry.’

He nodded, then turned his mount and began riding along the trail. After a long silence he said, ‘I still think you just have to do it.’

‘Maybe you’re right,’ she answered. ‘Look, did you keep any of the stuff your friends told you was great?’

With an embarrassed smile, he said, ‘All of it. The whole damn half novel.’

‘I’ll make you a deal. You let me see yours and I’ll let you see mine.’ Jack laughed hard at the school-yard phrase and shook his head. ‘What’s the matter? ’Fraid?’

‘No,’ Jack barely managed to croak as he continued to laugh uncontrollably.

‘Scaredy-cat,’ Gabbie mimicked, plunging Jack into deeper hilarity.

Jack finally said, ‘Okay, I give up. I’ll let you read my stuff … maybe.’

‘Maybe!’

The argument continued as they crested a small rise and vanished behind it. From deep within the woods a pair of light blue eyes watched their passing. A figure emerged from the underbrush, a lithe, youthful figure who moved lightly on bare feet to the top of the path. From behind a bole he watched Gabbie as she moved down the trail. His eyes caressed her young back, drinking in the sight of her long dark hair, her slender waist, and the rounded buttocks as she held a good seat on the horse’s back. The youth’s laughter was high-pitched and musical. It was an alien sound, childlike and ancient, holding a hint of savage songs, primitive revelries, and music-filled hot nights. His curly red-brown hair surrounded a face conceived by Michelangelo or a Pre-Raphaelite painter. ‘Pretty,’ the young man said to the tree, patting the ancient bark as if it understood. ‘Very pretty.’ Then, nearby, a bird sounded a call, and the youth looked up. His voice shrilled with inhuman tones, a whistling whisper, as if a mockingbird imitated the call. The little bird darted about, seeking the intruder in its territory. The youth shrieked in glee at the harmless jest, as the bird continued to search for the trespasser. Then the youth sighed as he considered the beautiful girl who had passed.

High above, among the leaves, a thing of blackness clung tenaciously to the underside of a branch. It had watched the two riders with as much interest as the youth. But its thoughts were neither merry nor playful. An urgent need arose within, halfway between lust and hunger. Beauty affected it as much as the youth. But its desires were different, for, while lust was the youth’s driving motivation, to the black thing under the tree branch beauty was only a beginning, a point of departure. And only the destruction of beauty allowed one to understand it. The fullness of Gabbie’s beauty could be realized only by a slow journey through pain and anguish, torment and hopelessness, ending with blood and death. And if the pain was artful, as the master had taught, such torment could be made to last for ages.

As it contemplated its alien dark thoughts, musing on the simple wonder of suffering, the black thing realized a truth. Whatever pleasure the girl’s destruction could produce would be nothing compared to the elation that could result from the destruction of the two boys. Such wonderful children, still innocent, still pure. They were the prize. Lingering terror and pain given to such as they would … The creature shuddered in dark anticipation at the image, then stilled itself, lest the one below take notice and make the black thing feel just such pain in turn. The youth stood another moment, one hand upon the tree, the other absently clutching at his groin as he held the image of the lovely human girl who had ridden past. Then, with a move like a spinning dance, the man-boy leaped back into the green vegetation, vanishing from mortal sight, leaving the small clearing empty save for the reverberations of impish laughter.

The black thing waited motionless after the youth vanished into the woods, for despite his youthful appearance, he was one to be feared, one who could cause great harm. When it was satisfied he was gone, and not playing one of his cruel tricks, it sprang with a powerful leap away from the tree. Its movements through the branches were alien, the articulation of its joints nothing of this world, as it hurried on its own errand of dark purpose.

• Chapter Eight • (#ulink_3b3cb4ff-7cb4-596e-809e-4ca340d055d6)

‘What’s your mother doing?’ asked Jack.

‘I don’t know. Last I heard she was off someplace in Central or South America, writing about another civil war or revolution.’ Gabbie sighed. ‘I don’t hear from her a lot, maybe three letters in the last five years. She and my dad split up when I was less than five. That’s when she got caught up doing the book on the fall of Saigon.’

‘I read it. It was brilliant.’

Gabbie nodded. ‘Mom is a brilliant writer. But as a mother she’s a totally lost cause.’

‘Look, if you’d rather not talk about it …’

‘That’s okay. Most of it’s public record. Mom tried writing a couple of novels before she and my father moved to California. Neither of my folks made much money from writing, but Mom hated Dad’s getting critical notice while she was getting rejection slips. Dad said she never showed much resentment, but it had to be one of the first strains on their marriage. Then Dad got the offer to adapt his second book, All the Fine Promises, and they moved to Hollywood. Dad wrote screenplays and made some solid money, and Mom had me. Then she got politically active in the antiwar movement, like, in ’68, right after the Tet Offensive. She wrote articles and pamphlets and then a publisher asked her to do a book, you know, Why We Resist.

‘It was pretty good, if a little heavy on polemics.’

Gabbie steered her horse round a fallen dead tree surrounded by brush. ‘Well, she might have written bad fiction, but her nonfiction was dynamite. She got her critical notice. And a lot of money. Things were never very good for them, but that’s when trouble really began and it got worse, fast. She’d get so involved in writing about the antiwar movement, then later the end of the war, that she’d leave him hanging all the time. Poor Dad, he’d have some studio dinner to go to or something and she’d not come home, or she’d show up in a flannel shirt and jeans at a formal reception, that sort of stuff. She became pretty radical. I was too young to remember any of it, but from what my grandmother told me, both of them acted pretty badly. But most folks say the breakup was Mom’s fault. She can get real bitchy and she’s stubborn. Even her own mother put most of the blame on her.

‘Anyway, Dad came home one night and found her packing. She’d just got special permission from the Swiss Government to take a Red Cross flight to Vietnam, to cover the fall of Saigon. But she had to leave that night. Things hadn’t been going well and Dad told her not to bother coming back if she left. So she didn’t.’

Jack nodded. ‘I don’t mean to judge, but it seemed a pretty special opportunity for your mother, I mean with Saigon about to fall, and all.’ He left unsaid the implication that her father had been unreasonable in his demand that his wife remain at home.

‘Ya. But I was in the hospital with meningitis at the time. I almost died, they tell me.’ Gabbie looked thoughtful for a while. ‘I can hardly remember what she looks like, except for pictures of her, and that’s not the same. Anyway, she became the radicals’ darling, and by the time the war was over she’d become a pretty well-respected political writer. Now she’s the grande dame of the Left, the spokesperson for populist causes all over the world. The only journalist allowed to interview Colonel Zamora when the rebels held him captive, and all that junk. You know all the rest.’

‘Must have been rough.’

‘I guess. I never knew it any different. Dad had to put in pretty rugged hours at the studio and travel on location and the rest, so he left me with my grandmother. Anyway, she raised me until I was about twelve, then I went to private school in Arizona. My father wanted me to come live with him when he married Gloria, but my grandmother wouldn’t allow it. I don’t know, but I think he tried to get me back and she threatened him.’ She fixed Jack with a narrow gaze. ‘The Larkers are an old family with old money, I mean, serious old money. Like Learjets and international corporations. And lawyers, maybe dozens all on retainer, and political clout, lots of it. I think Grandma Larker owned a couple of judges in Phoenix. Anyway, she could blow away any court action Dad could bring, even if he had some money by most people’s standards. So I stayed with her. Grandma was a little to the right of Attila the Hun, you know? Nig-grows, bleeding hearts, and “Communist outside agitators”? She thought Reagan was a liberal, Goldwater soft on communism, and the Birchers a terrific bunch of guys and gals. So even if she considered Mom a Commie flake, Grandma didn’t want me living with “that writer”, as she called Dad. She blamed Dad for Mom becoming a Commie flake, I guess. Anyway, Grandma Larker died two years ago, and I went to live with Dad. I lived with the family my last year in high school and my first year at UCLA. That’s it.’

Jack nodded, and Gabbie was surprised at what appeared to be genuine concern in his expression. She felt troubled by that, somehow, as if she was under inspection. She felt suddenly self-conscious at what she was certain was babbling. Urging her horse forward, she said, ‘What about you?’

Jack caught up with the walking horse and said, ‘Not much. Old North Carolina family. A many-greats-grandfather who chose raising horses instead of tobacco. Unfortunately, he bred slow racehorses, so all his neighbours got rich while he barely avoided bankruptcy. My family never had a lot of money, but we’ve got loads of genteel history’ – he laughed – ‘and slow horses. We’re big on tradition. No brothers or sisters. My father does research – physics – and teaches at UNC, which is why I went there as an undergraduate. My mother’s an old-fashioned housewife. My upbringing was pretty normal, I’m afraid.’

Gabbie sighed. ‘That sounds wonderful.’ Then, with a lightening tone, she said, ‘Come on, let’s put on some speed.’ She made to kick My Dandelion.

Before she could, Jack shouted, ‘No!’