По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

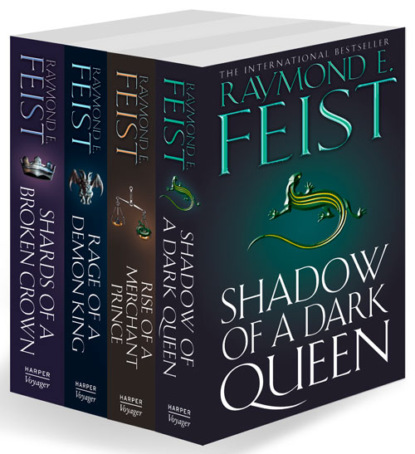

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’ll do what I can.’ He knew promising was vain should his mother take it into her head to repeat her performance of the last time Otto came through the town. ‘She may have finally gotten over making me the next Baron.’

Greylock made a sour face. ‘I would be out of place to comment on that.’ Then he softened his expression. ‘Trust me on this. If you can, stand by the corner of the town road where the sheep meadow ends and the first vineyard begins, on the east side of the town, before sunset.’

‘Why?’

‘I can’t say, but it’s important.’

‘If my father is so ill, Owen, what cause has he to ride to Krondor?’

Greylock mounted his horse. ‘Ill news, I’m afraid. The Prince is dead. It will be announced to the populace by royal messenger later this week.’

Erik said, ‘Arutha is dead?’

Greylock nodded. ‘He fell and broke his hip, I’ve been told, and died of complications. He was an aging man, nearly eighty if I have it right.’

Prince Arutha had been a fixture in Krondor all of Erik’s life and his mother’s before him. Father to the King, Borric, who had succeeded Arutha’s brother Lyam only five years earlier, he had been the man most responsible for peace in the Kingdom, by all accounts.

To Erik he was a distant figure; certainly, Erik had never seen the Prince, but he felt a small stab of regret. By anyone’s measure he was a good ruler and a hero in his youth. As Greylock turned the mare around, Erik said, ‘Tell my father I will stand where he asked.’

Greylock saluted and lightly touched spurs to the mare’s flanks, and she trotted out of the inn courtyard.

Nathan, who had come to understand a great deal of Erik’s history in the months he had been living at the Pintail, said, ‘You’ll want some extra time to clean up.’

Erik said, ‘I hadn’t thought of that. I was just going to leave at suppertime.’

It was late spring, and sunset came close to an hour after supper. Erik would need most of the hour to make it to the other side of Ravensburg, and through the vineyards to the sheep meadow, but only if he went in his dirty clothing.

Nathan playfully hit Erik on the back of the head with his open hand. ‘Dolt. Get yourself cleaned up. Sounds important.’

Erik thanked Nathan and hurried to the forge. Below the pallet in the loft where he slept, behind the ladder, sat a trunk with all of Erik’s belongings. He took out his one good shirt and carried it over to the washbasin. Removing his dirty shirt, he took the harsh soap and some clean rags and worked feverishly to rid himself of as much dirt as possible. At last he felt presentable and put on his good shirt.

He hurried out of the barn and went to the kitchen, where food was being placed upon the table as he entered. Sitting down, he drew a suspicious look from his mother. ‘Why are you wearing your good shirt?’ she asked.

Not willing to share his father’s request for a meeting with his mother, lest she demand to accompany him and force a confrontation, he muttered, ‘I’m meeting someone after supper,’ then started noisily eating the stew placed before him.

Milo, who was sitting at the head of the table, laughed. ‘One of the town girls, is it?’

This brought an alarmed look from Rosalyn, the color rising in her cheeks as Erik said, ‘Something like that.’

Erik continued to eat in silence, while Milo and Nathan spoke of the day’s events, and the women joined Erik in silence.

Nathan had a dry sense of humor that made it difficult at first to know if he was being mocking or merely amusing. This had resulted in Freida and Milo both treating him with some coolness at first.

But his warm nature and clear appreciation of life’s little moments had won over even Erik’s mother, who could often be seen trying to fight back a smile at some quip of Nathan’s. Erik had once asked him how he kept so even a disposition, and the answer had surprised him. ‘When you lose everything,’ Nathan had said, ‘you’ve nothing left to lose. You’ve got two choices then: either kill yourself or start building a new life. When I started this new life, without my family, I decided the only sensible thing in it was to live for the small rewards: a job well done, a beautiful sunrise, the sound of children laughing at play, a good cup of wine. Makes it easy to deal with the harsher side of life.

‘Kings and marshals can look back and relive their triumphs, their great victories. We common folk must take what pleasure we can from life’s little victories.’

Erik hardly touched his food, and at last bade everyone excuse him as he almost jumped up from the table and hurried out through the common room, Milo’s laughter following after. He almost ran through the door of the inn and barely avoided knocking Roo down as the youngster was about to enter the inn.

‘Wait a minute!’ cried Roo as he fell in beside his larger friend.

‘Can’t. I have to meet someone.’

Roo grabbed the larger youth by the arm and was almost dragged along a step or two before Erik stopped. ‘What?’ he asked Roo impatiently.

‘Did your father send for you?’

Erik had long since stopped being amazed at the town gossip Roo was able to ferret out, but this had him stunned. ‘Why do you ask that?’

Because since late yesterday the road has been thick with Kingdom Post riders, sometimes as many as three in a bunch, and a company of the Baron’s horse, followed by two companies of foot soldiers, passed by the eastern boundary of the town this morning, heading south, and the Baron’s own personal guards showed up an hour ago at the Growers’ and Vintners’ Hall. That’s what I was coming to tell you. And you’re wearing your best shirt.’

Not wishing to have Roo along, Erik said, ‘The Prince of Krondor is dead. That’s why …’ He was about to say that was why his father was coming to the town, on his way to Krondor, but instead said, ‘all the fuss.’

Roo said, ‘So those soldiers are heading south to support the garrisons along the Keshian border, in case the Emperor gets ambitious now that Arutha’s dead.’ Now suddenly an expert in military matters, Roo was left standing by Erik, who had resumed his hurried march.

Seeing he was suddenly alone, Roo yelled, ‘Hey!’ and chased after his friend, catching up with him as Erik left the street of the Pintail and entered the main square of the town.

‘Where are you going?’

Erik stopped. ‘I have to meet someone.’

‘Who?’

‘It’s personal.’

‘It’s not a girl, or you’d be heading north to the fountain, not east toward the baronial road.’ Roo’s eyes widened. ‘You are meeting your father! I was just joking before.’

Erik said, ‘I don’t want anyone to say anything, especially not to my mother.’

‘I’ll keep this to myself.’

‘Good,’ said Erik, turning Roo around with two large and powerful hands on narrow shoulders. ‘Go find something amusing to do, and not too illegal, and I’ll talk to you later tonight. Meet me at the inn.’

Roo frowned, but sauntered off as if he had intended to leave Erik alone anyway. Erik resumed his journey.

He hurried through the businesses clustered around the town square, two- and three-story edifices overhanging the narrow streets, then moved between the modest homes owned by the higher-ranking members of the various crafts and guilds, then the ramshackle houses used by workers, married apprentices, and traders without storefronts.

Leaving the town proper, he hurried along the east road, past small vegetable gardens where pushcart traders grew their wares to sell in the town market, and the large eastern vineyards. Reaching the point where the baronial road leading to Darkmoor intercepted the main east – west road through Ravensburg, he waited.

He mulled over what possible reason he could have been asked to meet his father at this relatively remote location, dismissing the most fanciful of all, that his mother’s dream would somehow be realized and his father would acknowledge him.

His musing was interrupted by the sound of an approaching company of horsemen. Soon he could see them crest a distant hill, a company of riders appearing out of the evening’s gloom to the northeast. As they neared, he could see they were the Baron’s own, leading the same carriage Erik had seen the last time the Baron had paid the town a visit. He felt a tightening in his chest as they neared, and no small apprehension, for his two half brothers could be seen riding beside the carriage. The first riders hurried past, but Stefan and Manfred reined in.

Stefan shouted, ‘What! You again?’

He made a threatening gesture as if to draw his sword, but his younger brother shouted, ‘Stefan! Keep up! Leave him alone!’

The younger brother set heels to his mount and moved to keep up with the vanguard, but his older brother hesitated.