По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

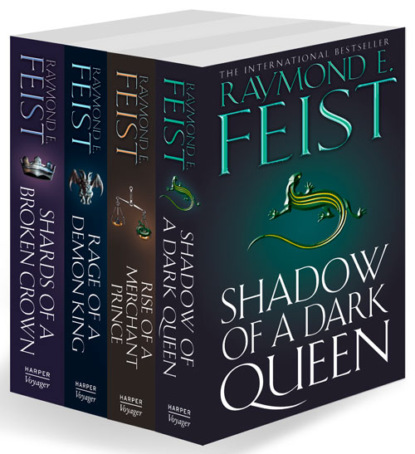

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Erik remained silent, and after a moment Nathan said, ‘Thoughtful, is it? That’s good. Now, here’s the choice of it: you can stay and learn and perfect your skills and I’ll count myself a lucky sod for having a second pair of trained hands around, belonging to someone I don’t have to teach every tiny thing. Or you can brood and be resentful, and think you know as much as I, and be useless to us both. There’s only room for one master in this forge, boy, and I am he. So there’s the end of it, and there’s the choice. Do you need time to think on this?’

Erik paused, then said, ‘No. I need no time to think about it, Master Nathan.’ Sighing, he added, ‘You are correct. There is only one master in a forge. I …’

‘Spit it out, boy.’

I have been responsible around here for so long I feel as if it is my forge, and that I should have been given it by the guild.’

Nathan nodded once. ‘That’s understandable.’

‘But it’s not your fault Tyndal was a slacker and my time here counts for nothing.’

‘None of that, boy –’

‘Erik. My name is Erik.’

‘None of that, Erik,’ said Nathan; then suddenly he swung hard and connected a roundhouse right that knocked Erik onto his backside. ‘And I told you, interrupt me again and I’d cease being civil. I am a man of my word.’

Erik sat rubbing his jaw, astonishment on his face. He knew the smith had pulled the blow, but he could feel the sting of it anyway. After a moment he said, ‘Yes, sir.’

Nathan put out his hand and Erik took it. The smith pulled Erik to his feet. ‘I was about to say that any time spent learning a craft counts. You only lack credentials. If you’re as good as you think you are, you’ll be certified in the minimum seven years. You’ll be older than most journeymen when you seek your own forge, but you’ll be younger than some, trust me on that. There are slower lads that don’t leave their master’s forge until they are in their late twenties. Remember this: you may be coming late to your office, but your learning started four years earlier than most boys’ as well. Knowledge is knowledge, and experience is experience, so you should have a far shorter time of it from journeyman to master. In the end, it will all work out.’

Turning slowly, as if examining the smithy once again, he said, ‘And from what I see here, if you can keep your head right, we’ll get along fine.’

There was an open friendliness in that remark which caused Erik to forget his stinging jaw. He nodded. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Now, show me where I sleep.’

Without being told, Erik picked up the smith’s travel bag and cloak, and motioned. ‘Tyndal had no family, so he slept here. There’s a small room around back, and I sleep in the loft up there.’ Erik pointed to the only place he’d called his own for the last six years. ‘I never thought about moving into Tyndal’s room – habit, I guess.’ He led the smith out the rear door and to the shed that Tyndal had used for his bedroom.

‘My former master was drunk most of the time, so I fear this room is likely to be …’ He opened the door.

The smell that greeted them almost made Erik gag. Nathan only stood a moment, then stepped away as he said, ‘I’ve worked with drunkards before, lad, and that’s the smell of sour sickness. Never seek to hide in a wine bottle, Erik. It’s a slow and painful death. Meet your sorrows head on, and after you’ve wrestled with them, put them behind.’

Something in his tone told Erik that Nathan wasn’t simply repeating an aphorism but was speaking from belief. ‘I can put this room right, sir, while you take your ease at the inn.’

‘I’d best make myself known to the innkeeper; he is to be my landlord, after all. And I could use something to eat.’

Erik realized he hadn’t thought of that. The office of guild smith might be granted by the guild and a patent for a town might be exclusive, but otherwise the smith was like any other tradesman, forced to make a profit the best he knew how, and responsible for setting up his own place of business. Erik said, ‘Sir, Tyndal had no family. Who …’

Nathan put his hand on Erik’s shoulder. ‘Who should I be paying for all these tools?’

Erik nodded.

Nathan said, ‘My own tools will be coming by freight hauler any day now. I have no desire to take what is not rightfully mine, Erik.’ He scratched his day’s growth of whiskers as he thought. ‘When you’re ready to leave Ravensburg and begin your own forge, let us assume they go with you. You were his last apprentice, and tradition has it that you are to pay the widow for the tools. As he had no family, there’s no one to pay, is there?’

Erik realized what an incredibly generous offer he was being made. An apprentice was expected somehow to supplement his earnings so that by the time he reached journeyman’s rank he could purchase a complete set of tools, and an anvil, and have the money to pay for the construction of a forge if needed. Most young journeymen were able to begin modestly, but Tyndal, for all his sloth in his last years, had been a master smith for seventeen years and had every conceivable tool of the trade, two and three of some. With proper care and cleaning, Erik would be set up for life!

Erik said, ‘If you would like, I can show you to the kitchen.’

‘I’ll find my way. Just come get me when this room is cleaned up.’

Erik nodded, and as Nathan moved off toward the rear of the inn, the boy held his breath and went into Tyndal’s room. Throwing open the single window didn’t help, and Erik hurried back outside because of the stench. Unpleasant odors bothered Erik, strong as he was in most ways, and he confessed to a weak stomach. Though he was used to the smell of the barn and forge, nevertheless the odor of human illness and waste caused the bile to rise in his gorge, and he had tears in his eyes from the reek by the time he got Tyndal’s bedding outside the hut.

Breathing through his mouth and turning his head away, he hurried to the large iron tub his mother used for washing and threw the filthy linens into it. As he was building up the fire beneath, his mother approached.

‘Who is this man claiming to be the new smith?’ she demanded.

Erik was in no mood to battle his mother, so he calmly said, ‘Not claiming; is. The guild sent him.’

‘Well, did you tell him there already was a smith here?’

Erik got the fire under the tub going and stood up. As calmly as he could manage, he said, ‘No. This is a guild forge. And I have no standing with the guild.’ Thinking of Tyndal’s tools, he added, ‘Nathan’s being very generous and is keeping me on. He’ll apprentice me to the guild and …’

Erik expected an argument, but instead his mother only nodded once and left without further comment. Puzzled by her lack of outburst, Erik stood a moment until the crackling of the fire under the tub reminded him he had a still-unfinished task. He took one of the hard cakes of soap used to wash the inn’s bedding and broke it in half. Tossing the hard soap into the tub, he began stirring with a paddle. As the water turned a deep brown, he thought: why no argument from his mother? There was an air of resignation from her that he had never seen before.

Leaving the sheets to simmer in the tub, Erik hurried back to the smith’s room, grabbing some rags and a mineral oil cleaner he used on especially filthy tack and tools. He removed the balance of Tyndal’s possessions, a single large chest and a sack of personal items. A rickety wooden wardrobe he left inside, in case Nathan choose to hang his cloaks and shirts there; he could always haul it away later if the new smith didn’t care for it.

When he had the last of Tyndal’s possessions outside, Erik regarded the meager pile. ‘Not a lot to show for a lifetime,’ he muttered. He picked up the chest and hauled it over to one corner of the small yard behind the barn, and picked up the sack and placed it on top. He’d go through them later to see what Tyndal had left that might be of use. There were always poor farmers on the outskirts of the vineyards who grew other than grapes, and they always could use serviceable clothing.

Then Erik took the rags and cleaner and began scrubbing years of accumulated grime off the walls.

Erik entered the kitchen to find Milo sitting at the big table, staring across at Nathan, who was finishing a large bowl of stew. Milo was nodding at something the smith had just said, while Freida and Rosalyn both made busy preparing vegetables for the evening meal.

Erik glanced at his mother, who stood expressionless at the sink, listening to the men speak. Rosalyn inclined her head toward Erik’s mother, indicating concern. Erik nodded briefly, then moved beside his mother, indicating he wished to wash up. She nodded curtly and moved toward the oven, where the bread purchased that morning from the baker was being kept warm.

Nathan continued what he had been saying when Erik entered. ‘While I have the knack with iron, I’m indifferent with horses, truth to tell, above the legs. I can adjust a shoe to balance a lameness, or to compensate for some other problem, but when it comes to the rest, I’m as simple as anyone.’

‘Then you’ve chosen wisely to keep Erik on,’ said Milo, showing an almost fatherly pride. He’s a wonder with horses.’

Rosalyn asked, ‘Master Smith, from what you’ve said, you could have had any number of large baronial forges, or even a ducal charge. Why did you pick our small town?’

Nathan pushed away the bowl of stew he had finished, and smiled. ‘I’m a lover of wine, truth to tell, and this is a great change from my former home.’

Freida turned and blurted, ‘We’re scant weeks past burying one smith for the love of too much wine, and now we’ve another! The gods must hate Ravensburg indeed!’

Nathan looked at Freida and spoke. His tone was measured, but it was clear he was not far from anger. ‘Good woman, I love the wine, but I’m no mean drunkard. I was a father and husband who took care of his own for many years. If I drink more than a glass in a day, it’s a festival. I’ll thank you to pass no judgment on matters you know nothing about. Smiths are no more cut from the same bolt of cloth as all men of any other trade are alike in all ways.’

Freida turned away, her color rising slightly, but she said nothing save, ‘The fire is too warm. This bread will be dry before supper.’ She made a show of turning the coals, though everyone knew it was unnecessary.

Erik watched his mother for a moment, then turned toward Nathan. ‘The room is clean, sir.’

Freida snapped, ‘Will you all be sharing that one tiny room?’

Nathan rose, picking up his cloak and leaning over to retrieve his bag. As he hoisted his possessions, he said, ‘All?’

‘These children and your wife you spoke so tenderly of?’

Nathan’s tone was calm when he replied, ‘All dead. Killed by raiders in the sacking of the Far Coast. I was senior journeyman to Baron Tolburt’s Master Smith at Tulan.’ The room was still as he continued. ‘I was asleep, but the sound of fighting woke me. I told my Martha to see to the children as I ran to the forge. I took no more than two steps out the door of the servants’ quarters when I was struck twice by arrows’ – he touched his shoulder, then his left thigh – ‘here and here. I fainted. Another man fell on top of me, I think. Anyway, my wife and children were already dead when I awoke the next day.’ He glanced around the room. ‘We had four children, three boys and a girl.’ He sighed. ‘Little Sarah was special.’ He fell silent for a long moment, and his face took on a reflective expression. Then he said, ‘Damn me. It’s nearly twenty-five years now.’ Without another word he rose, and nodded his head once to Milo, then moved to the door.