По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

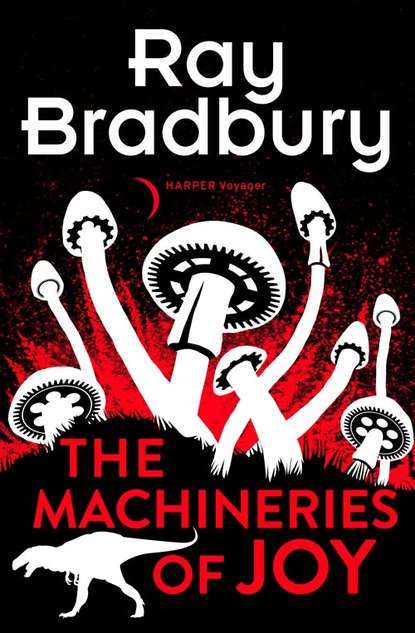

The Machineries of Joy

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“God bless us all, said Tiny Tim. He’s laughing, almost hysterical with relief.”

“So maybe I know why,” said Mr. Glass. “A little girl, after the preview, asked him for an autograph.”

“An autograph?”

“Right there in the street. Made him sign. First autograph he ever gave in his life. He laughed all the while he wrote his name. Somebody knew him. There he was, in front of the theater, big as life, Rex Himself, so sign the name. So he did.”

“Wait a minute,” said Terwilliger slowly, pouring drinks. “That little girl …?”

“My youngest daughter,” said Glass. “So who knows? And who will tell?”

They drank.

“Not me,” said Terwilliger.

Then, carrying the rubber dinosaur between them, and bringing the whisky, they went to stand by the studio gate, waiting for the limousines to arrive all lights, horns and annunciations.

The Vacation (#ulink_e5a38d74-ad9f-5bc8-be50-53eae19c8d9a)

It was a day as fresh as grass growing up and clouds going over and butterflies coming down can make it. It was a day compounded from silences of bee and flower and ocean and land, which were not silences at all, but motions, stirs, flutters, risings, fallings, each in its own time and matchless rhythm. The land did not move, but moved. The sea was not still, yet was still. Paradox flowed into paradox, stillness mixed with stillness, sound with sound. The flowers vibrated and the bees fell in separate and small showers of golden rain on the clover. The seas of hill and the seas of ocean were divided, each from the other’s motion, by a railroad track, empty, compounded of rust and iron marrow, a track on which, quite obviously, no train had run in many years. Thirty miles north it swirled on away to further mists of distance, thirty miles south it tunneled islands of cloud-shadow that changed their continental positions on the sides of far mountains as you watched.

Now, suddenly, the railroad track began to tremble.

A blackbird, standing on the rail, felt a rhythm grow faintly, miles away, like a heart beginning to beat.

The blackbird leaped up over the sea.

The rail continued to vibrate softly until, at long last, around a curve and along the shore came a small workman’s handcar, its two-cylinder engine popping and spluttering in the great silence.

On top of this small four-wheeled car, on a double-sided bench facing in two directions and with a little surrey roof above for shade, sat a man, his wife and their small seven-year-old son. As the handcar traveled through lonely stretch after lonely stretch, the wind whipped their eyes and blew their hair, but they did not look back but only ahead. Sometimes they looked eagerly as a curve unwound itself, sometimes with great sadness, but always watchful, ready for the next scene.

As they hit a level straightaway, the machine engine gasped and stopped abruptly. In the now crushing silence, it seemed that the quiet of earth, sky and sea itself, by its friction, brought the car to a wheeling halt.

“Out of gas.”

The man, sighing, reached for the extra can in the small storage bin and began to pour it into the tank.

His wife and son sat quietly looking at the sea, listening to the muted thunder, the whisper, the drawing back of huge tapestries of sand, gravel, green weed, and foam.

“Isn’t the sea nice?” said the woman.

“I like it,” said the boy.

“Shall we picnic here, while we’re at it?”

The man focused some binoculars on the green peninsula ahead.

“Might as well. The rails have rusted badly. There’s a break ahead. We may have to wait while I set a few back in place.”

“As many as there are,” said the boy, “we’ll have picnics!”

The woman tried to smile at this, then turned her grave attention to the man. “How far have we come today?”

“Not ninety miles.” The man still peered through the glasses, squinting. “I don’t like to go farther than that any one day, anyway. If you rush, there’s no time to see. We’ll reach Monterey day after tomorrow, Palo Alto the next day, if you want.”

The woman removed her great shadowing straw hat, which had been tied over her golden hair with a bright yellow ribbon, and stood perspiring faintly, away from the machine. They had ridden so steadily on the shuddering rail car that the motion was sewn into their bodies. Now, with the stopping, they felt odd, on the verge of unraveling.

“Let’s eat!”

The boy ran the wicker lunch basket down to the shore.

The boy and the woman were already seated by a spread table-cloth when the man came down to them, dressed in his business suit and vest and tie and hat as if he expected to meet someone along the way. As he dealt out the sandwiches and exhumed the pickles from their cool green Mason jars, he began to loosen his tie and unbutton his vest, always looking around as if he should be careful and ready to button up again.

“Are we all alone, Papa?” said the boy, eating.

“Yes.”

“No one else, anywhere?”

“No one else.”

“Were there people before?”

“Why do you keep asking that? It wasn’t that long ago. Just a few months. You remember.”

“Almost. If I try hard, then I don’t remember at all.” The boy let a handful of sand fall through his fingers. “Were there as many people as there is sand here on the beach? What happened to them?”

“I don’t know,” the man said, and it was true.

They had wakened one morning and the world was empty. The neighbors’ clothesline was still strung with blowing white wash, cars gleamed in front of other 7-A.M. cottages, but there were no farewells, the city did not hum with its mighty arterial traffics, phones did not alarm themselves, children did not wail in sunflower wildernesses.

Only the night before, he and his wife had been sitting on the front porch when the evening paper was delivered, and, not even daring to open the headlines out, he had said, “I wonder when He will get tired of us and just rub us all out?”

“It has gone pretty far,” she said. “On and on. We’re such fools, aren’t we?”

“Wouldn’t it be nice—” he lit his pipe and puffed it—“if we woke tomorrow and everyone in the world was gone and everything was starting over?” He sat smoking, the paper folded in his hand, his head resting back on the chair.

“If you could press a button right now and make it happen, would you?”

“I think I would,” he said. “Nothing violent. Just have everyone vanish off the face of the earth. Just leave the land and the sea and the growing things, like flowers and grass and fruit trees. And the animals, of course, let them stay. Everything except man, who hunts when he isn’t hungry, eats when full, and is mean when no one’s bothered him.”

“Naturally, we would be left.” She smiled quietly.

“I’d like that,” he mused. “All of time ahead. The longest summer vacation in history. And us out for the longest picnic-basket lunch in memory. Just you, me and Jim. No commuting. No keeping up with the Joneses. Not even a car. I’d like to find another way of traveling, an older way. Then, a hamper full of sandwiches, three bottles of pop, pick up supplies where you need them from empty grocery stores in empty towns, and summertime forever up ahead …”

They sat a long while on the porch in silence, the newspaper folded between them.

At last she opened her mouth.