По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

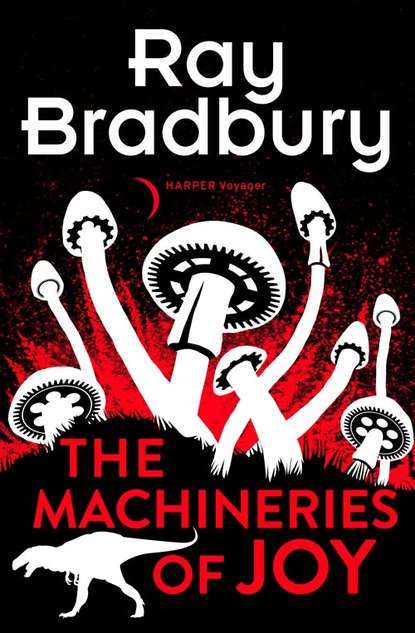

The Machineries of Joy

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Yes,” said Terwilliger. A faint ghost of screen haunted the dark theater wall to his right. To his left, a cigarette wove fiery arcs in the air as someone’s lips talked swiftly around it.

“You’re five minutes late!”

Don’t make it sound like five years, thought Terwilliger.

“Shove your film in the projection room door. Let’s move.”

Terwilliger squinted.

He made out five vast loge seats that exhaled, breathed heavily as amplitudes of executive life shifted, leaning toward the middle loge where, almost in darkness, a little boy sat smoking.

No, thought Terwilliger, not a boy. That’s him. Joe Clarence. Clarence the Great.

For now the tiny mouth snapped like a puppet’s, blowing smoke. “Well?”

Terwilliger stumbled back to hand the film to the projectionist, who made a lewd gesture toward the loges, winked at Terwilliger and slammed the booth door.

“Jesus,” sighed the tiny voice. A buzzer buzzed. “Roll it, projection!”

Terwilliger probed the nearest loge, struck flesh, pulled back and stood biting his lips.

Music leaped from the screen. His film appeared in a storm of drums:

TYRANNOSAURUS REX: The Thunder Lizard.

Photographed in stop-motion animation with miniatures created by John Terwilliger. A study in life-forms on Earth one billion years before Christ.

Faint ironic applause came softly patting from the baby hands in the middle loge.

Terwilliger shut his eyes. New music jerked him alert. The last titles faded into a world of primeval sun, mist, poisonous rain and lush wilderness. Morning fogs were strewn along eternal seacoasts where immense flying dreams and dreams of nightmare scythed the wind. Huge triangles of bone and rancid skin, of diamond eye and crusted tooth, pterodactyls, the kites of destruction, plunged, struck prey, and skimmed away, meat and screams in their scissor mouths.

Terwilliger gazed, fascinated.

In the jungle foliage now, shiverings, creepings, insect jitterings, antennae twitchings, slime locked in oily fatted slime, armor skinned to armor, in sun glade and shadow moved the reptilian inhabitors of Terwilliger’s mad remembrance of vengeance given flesh and panic taking wing.

Brontosaur, stegosaur, triceratops. How easily the clumsy tonnages of name fell from one’s lips.

The great brutes swung like ugly machineries of war and dissolution through moss ravines, crushing a thousand flowers at one footfall, snouting the mist, ripping the sky in half with one shriek.

My beauties, thought Terwilliger, my little lovelies. All liquid latex, rubber sponge, ball-socketed steel articulature; all night-dreamed, clay-molded, warped and welded, riveted and slapped to life by hand. No bigger than my fist, half of them; the rest no larger than this head they sprang from.

“Good Lord,” said a soft admiring voice in the dark.

Step by step, frame by frame of film, stop motion by stop motion, he, Terwilliger, had run his beasts through their postures, moved each a fraction of an inch, photographed them, moved them another hair, photographed them, for hours and days and months. Now these rare images, this eight hundred scant feet of film, rushed through the projector.

And lo! he thought. I’ll never get used to it. Look! They come alive!

Rubber, steel, clay, reptilian latex sheath, glass eye, porcelain fang, all ambles, trundles, strides in terrible prides through continents as yet unmanned, by seas as yet unsalted, a billion years lost away. They do breathe. They do smite air with thunders. Oh, uncanny!

I feel, thought Terwilliger, quite simply, that there stands my Garden, and these my animal creations which I love on this Sixth Day, and tomorrow, the Seventh, I must rest.

“Lord,” said the soft voice again.

Terwilliger almost answered, “Yes?”

“This is beautiful footage, Mr. Clarence,” the voice went on.

“Maybe,” said the man with a boy’s voice.

“Incredible animation.”

“I’ve seen better,” said Clarence the Great.

Terwilliger stiffened. He turned from the screen where his friends lumbered into oblivion, from butcheries wrought on architectural scales. For the first time he examined his possible employers.

“Beautiful stuff.”

This praise came from an old man who sat to himself far across the theater, his head lifted forward in amaze toward that ancient life.

“It’s jerky. Look there!” The strange boy in the middle loge half rose, pointing with the cigarette in his mouth. “Hey, was that a bad shot. You see?”

“Yes,” said the old man, tired suddenly, fading back in his chair. “I see.”

Terwilliger crammed his hotness down upon a suffocation of swiftly moving blood.

“Jerky,” said Joe Clarence.

White light, quick numerals, darkness; the music cut, the monsters vanished.

“Glad that’s over.” Joe Clarence exhaled. “Almost lunchtime. Throw on the next reel, Walter! That’s all, Terwilliger.” Silence. “Terwilliger?” Silence. “Is that dumb bunny still here?”

“Here.” Terwilliger ground his fists on his hips.

“Oh,” said Joe Clarence. “It’s not bad. But don’t get ideas about money. A dozen guys came here yesterday to show stuff as good or better than yours, tests for our new film, Prehistoric Monster. Leave your bid in an envelope with my secretary. Same door out as you came in. Walter, what the hell you waiting for? Roll the next one!”

In darkness, Terwilliger barked his shins on a chair, groped for and found the door handle, gripped it tight, tight.

Behind him the screen exploded: an avalanche fell in great flourings of stone, whole cities of granite, immense edifices of marble piled, broke and flooded down. In this thunder, he heard voices from the week ahead:

“We’ll pay you one thousand dollars, Terwilliger.”

“But I need a thousand for my equipment alone!”

“Look, we’re giving you a break. Take it or leave it!”

With the thunder dying, he knew he would take, and he knew he would hate it.

Only when the avalanche had drained off to silence behind him and his own blood had raced to the inevitable decision and stalled in his heart, did Terwilliger pull the immensely weighted door wide to step forth into the terrible raw light of day.