По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

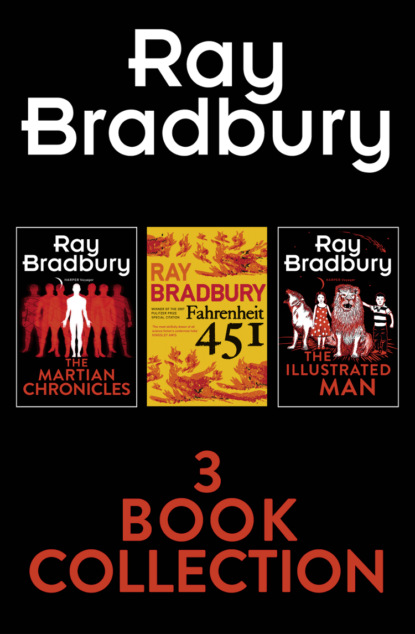

Ray Bradbury 3-Book Collection: Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Montag’s head whirled sickeningly. He felt beaten unmercifully on brow, eyes, nose, lips, chin, on shoulders, on upflailing arms. He wanted to yell, ‘No! shut up, you’re confusing things, stop it!’ Beatty’s graceful fingers thrust out to seize his wrist.

‘God, what a pulse! I’ve got you wrong, have I, Montag. Jesus God, your pulse sounds like the day after the war. Everything but sirens and bell! Shall I talk some more? I like your look of panic. Swahili, Indian, English Lit, I speak them all. A kind of excellent dumb discourse, Willie!’

‘Montag, hold on!’ The mouth brushed Montag’s ear. ‘He’s muddying the waters!’

‘Oh, you were scared silly,’ said Beatty, ‘for I was doing a terrible thing in using the very books you clung to, to rebut you on every hand, on every point! What traitors books can be! You think they’re backing you up, and they turn on you. Others can use them, too, and there you are, lost in the middle of the moor, in a great welter of nouns and verbs and adjectives. And at the very end of my dream, along I came with the Salamander and said, Going my way? And you got in and we drove back to the firehouse in beatific silence, all dwindled away to peace.’ Beatty let Montag’s wrist go, let the hand slump limply on the table. ‘All’s well that is well in the end.’

Silence. Montag sat like a carved white stone. The echo of the final hammer on his skull died slowly away into the black cavern where Faber waited for the echoes to subside. And then when the startled dust had settled down about Montag’s mind, Faber began, softly, ‘All right, he’s had his say. You must take it in. I’ll say my say, too, in the next few hours. And you’ll take it in. And you’ll try to judge them and make your decision as to which way to jump, or fall. But I want it to be your decision, not mine, and not the Captain’s. But remember that the Captain belongs to the most dangerous enemy of truth and freedom, the solid unmoving cattle of the majority. Oh, God, the terrible tyranny of the majority. We all have our harps to play. And it’s up to you now to know with which ear you’ll listen.’

Montag opened his mouth to answer Faber and was saved this error in the presence of others when the station bell rang. The alarm-voice in the ceiling chanted. There was a tacking-tacking sound as the alarm-report telephone typed out the address across the room. Captain Beatty, his poker cards in one pink hand, walked with exaggerated slowness to the phone and ripped out the address when the report was finished. He glanced perfunctorily at it, and shoved it in his pocket. He came back and sat down. The others looked at him.

‘It can wait exactly forty seconds while I take all the money away from you,’ said Beatty, happily.

Montag put his cards down.

‘Tired, Montag? Going out of this game?’

‘Yes.’

‘Hold on. Well, come to think of it, we can finish this hand later. Just leave your cards face down and hustle the equipment. On the double now.’ And Beatty rose up again. ‘Montag, you don’t look well? I’d hate to think you were coming down with another fever …’

‘I’ll be all right.’

‘You’ll be fine. This is a special case. Come on, jump for it!’

They leaped into the air and clutched the brass pole as if it were the last vantage point above a tidal wave passing below, and then the brass pole, to their dismay slid them down into darkness, into the blast and cough and suction of the gaseous dragon roaring to life!

‘Hey!’

They rounded a corner in thunder and siren, with concussion of tyres, with a scream of rubber, with a shift of kerosene bulk in the glittery brass tank, like the food in the stomach of a giant, with Montag’s fingers jolting off the silver rail, swinging into cold space, with the wind tearing his hair back from his head, with the wind whistling in his teeth, and him all the while thinking of the women, the chaff women in his parlour tonight, with the kernels blown out from under them by a neon wind, and his silly damned reading of a book to them. How like trying to put out fires with water-pistols, how senseless and insane. One rage turned in for another. One anger displacing another. When would he stop being entirely mad and be quiet, be very quiet indeed?

‘Here we go!’

Montag looked up. Beatty never drove, but he was driving tonight, slamming the Salamander around corners, leaning forward high on the driver’s throne, his massive black slicker flapping out behind so that he seemed a great black bat flying above the engine, over the brass numbers, taking the full wind.

‘Here we go to keep the world happy, Montag!’

Beatty’s pink, phosphorescent cheeks glimmered in the high darkness, and he was smiling furiously.

‘Here we are!’

The Salamander boomed to a halt, throwing men off in slips and clumsy hops. Montag stood fixing his raw eyes to the cold bright rail under his clenched fingers.

I can’t do it, he thought. How can I go at this new assignment, how can I go on burning things? I can’t go in this place.

Beatty, smelling of the wind through which he had rushed, was at Montag’s elbow. ‘All right, Montag?’

The men ran like cripples in their clumsy boots, as quietly as spiders.

At last Montag raised his eyes and turned. Beatty was watching his face.

‘Something the matter, Montag?’

‘Why,’ said Montag slowly, ‘we’ve stopped in front of my house.’

PART THREE (#ulink_9ecb4c6d-d8e6-50bb-a3de-ee6aad4a129f)

Lights flicked on and house-doors opened all down the street, to watch the carnival set up. Montag and Beatty stared, one with dry satisfaction, the other with disbelief, at the house before them, this main ring in which torches would be juggled and fire eaten.

‘Well,’ said Beatty, ‘now you did it. Old Montag wanted to fly near the sun and now that he’s burnt his damn wings, he wonders why. Didn’t I hint enough when I sent the Hound around your place?’

Montag’s face was entirely numb and featureless; he felt his head turn like a stone carving to the dark place next door, set in its bright borders of flowers.

Beatty snorted. ‘Oh, no! You weren’t fooled by that little idiot’s routine, now, were you? Flowers, butterflies, leaves, sunsets, oh, hell! It’s all in her file. I’ll be damned. I’ve hit the bullseye. Look at the sick look on your face. A few grassblades and the quarters of the moon. What trash. What good did she ever do with all that?’

Montag sat on the cold fender of the Dragon, moving his head half an inch to the left, half an inch to the right, left, right, left right, left …

‘She saw everything. She didn’t do anything to anyone. She just let them alone.’

‘Alone, hell! She chewed around you, didn’t she? One of those damn do-gooders with their shocked, holier-than-thou silences, their one talent making others feel guilty. God damn, they rise like the midnight sun to sweat you in your bed!’

The front door opened; Mildred came down the steps, running, one suitcase held with a dream-like clenching rigidity in her fist, as a beetle-taxi hissed to the kerb.

‘Mildred!’

She ran past with her body stiff, her face floured with powder, her mouth gone, without lipstick.

‘Mildred, you didn’t put in the alarm!’

She shoved the valise in the waiting beetle, climbed in, and sat mumbling, ‘Poor family, poor family, oh everything gone, everything, everything gone now …’

Beatty grabbed Montag’s shoulder as the beetle blasted away and hit seventy miles an hour, far down the street, gone.

There was a crash like the falling parts of a dream fashioned out of warped glass, mirrors, and crystal prisms. Montag drifted about as if still another incomprehensible storm had turned him, to see Stoneman and Black wielding axes, shattering window-panes to provide cross-ventilation.

The brush of a death’s-head moth against a cold black screen. ‘Montag, this is Faber. Do you hear me? What is happening?’

‘This is happening to me,’ said Montag.

‘What a dreadful surprise,’ said Beatty. ‘For everyone nowadays knows, absolutely is certain, that nothing will ever happen to me. Others die, I go on. There are no consequences and no responsibilities. Except that there are. But let’s not talk about them, eh? By the time the consequences catch up with you, it’s too late, isn’t it, Montag?’

‘Montag, can you get away, run?’ asked Faber.

Montag walked but did not feel his feet touch the cement and then the night grasses. Beatty flicked his igniter nearby and the small orange flame drew his fascinated gaze.

‘What is there about fire that’s so lovely? No matter what age we are, what draws us to it?’ Beatty blew out the flame and lit it again. ‘It’s perpetual motion; the thing man wanted to invent but never did. Or almost perpetual motion. If you let it go on, it’d burn our lifetimes out. What is fire? It’s a mystery. Scientists give us gobbledegook about friction and molecules. But they don’t really know. Its real beauty is that it destroys responsibility and consequences. A problem gets too burdensome, then into the furnace with it. Now, Montag, you’re a burden. And fire will lift you off my shoulders, clean, quick, sure; nothing to rot later. Antibiotic, aesthetic, practical.’

Montag stood looking in now at this queer house, made strange by the hour of the night, by murmuring neighbour voices, by littered glass, and there on the floor, their covers torn off and spilled out like swan-feathers, the incredible books that looked so silly and really not worth bothering with, for these were nothing but black type and yellowed paper and ravelled binding.