По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

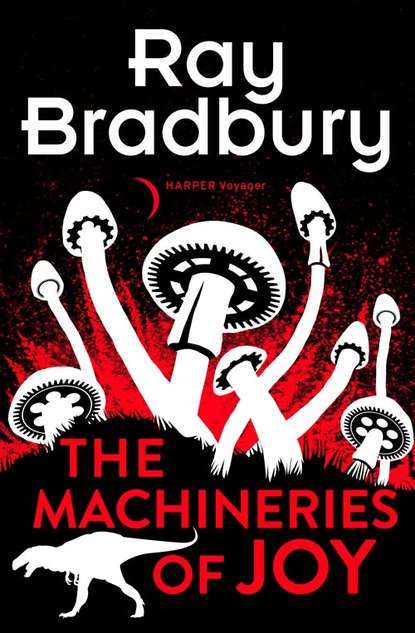

The Machineries of Joy

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I hope nobody said that,” said Father Kelly.

“I am an angry man,” said Father Brian. “In my anger I might have inferred it.”

“Angry, why? And inferred for what reason?”

“Did you hear what he just said about the twenty-fifth century?” asked Father Brian. “Well, it’s when Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers fly in through the baptistry transom that yours truly hunts for the exits.”

Father Kelly sighed. “Ah, God, is it that joke again?”

Father Brian felt the blood burn his cheeks, but fought to send it back to cooler regions of his body.

“Joke? It’s off and beyond that. For a month now it’s Canaveral this and trajectories and astronauts that. You’d think it was Fourth of July, he’s up half each night with the rockets. I mean, now, what kind of life is it, from midnight on, carousing about the entryway with that Medusa machine which freezes your intellect if ever you stare at it? I cannot sleep for feeling the whole rectory will blast off any minute.”

“Yes, yes,” said Father Kelly. “But what’s all this about the Pope?” “Not the new one, the one before the last,” said Brian wearily. “Show him the clipping, Father Vittorini.” Vittorini hesitated. “Show it,” insisted Brian, firmly.

Father Vittorini brought forth a small press clipping and put it on the table.

Upside down, even, Father Brian could read the bad news: “POPE BLESSES ASSAULT ON SPACE.”

Father Kelly reached one finger out to touch the cutting gingerly. He intoned the news story half aloud, underlining each word with his fingernail:

CASTEL GANDOLFO, ITALY, SEPT. 20.—Pope Pius XII gave his blessing today to mankind’s efforts to conquer space.

The Pontiff told delegates to the International Astronautical Congress, “God has no intention of setting a limit to the efforts of man to conquer space.”

The 400 delegates to the 22-nation congress were received by the Pope at his summer residence here.

“This Astronautic Congress has become one of great importance at this time of man’s exploration of outer space,” the Pope said. “It should concern all humanity.… Man has to make the effort to put himself in new orientation with God and his universe.”

Father Kelly’s voice trailed off.

“When did this story appear?”

“In 1956.”

“That long back?” Father Kelly laid the thing down. “I didn’t read it.”

“It seems,” said Father Brian, “you and I, Father, don’t read much of anything.”

“Anyone could overlook it,” said Kelly. “It’s a teeny-weeny article.”

“With a very large idea in it,” added Father Vittorini, his good humor prevailing.

“The point is—”

“The point is,” said Vittorini, “when first I spoke of this piece, grave doubts were cast on my veracity. Now we see I have cleaved close by the truth.”

“Sure,” said Father Brian quickly, “but as our poet William Blake put it, ‘A truth that’s told with bad intent beats all the lies you can invent.’”

“Yes.” Vittorini relaxed further into his amiability. “And didn’t Blake also write

He who doubts from what he sees,

Will ne’er believe, do what you please.

If the Sun and Moon should doubt

They’d immediately go out.

Most appropriate,” added the Italian priest, “for the Space Age.”

Father Brian stared at the outrageous man.

“I’ll thank you not to quote our Blake at us.”

“Your Blake?” said the slender pale man with the softly glowing dark hair. “Strange, I’d always thought him English.”

“The poetry of Blake,” said Father Brian, “was always a great comfort to my mother. It was she told me there was Irish blood on his maternal side.”

“I will graciously accept that,” said Father Vittorini. “But back to the newspaper story. Now that we’ve found it, it seems a good time to do some research on Pius the Twelfth’s encyclical.”

Father Brian’s wariness, which was a second set of nerves under his skin, prickled alert.

“What encyclical is that?”

“Why, the one on space travel.”

“He didn’t do that?”

“He did.”

“On space travel, a special encyclical?”

“A special one.”

Both Irish priests were near onto being flung back in their chairs by the blast.

Father Vittorini made the picky motions of a man cleaning up after a detonation, finding lint on his coat sleeve, a crumb or two of toast on the tablecloth.

“Wasn’t it enough,” said Brian, in a dying voice, “he shook hands with the astronaut bunch and told them well done and all that, but he had to go on and write at length about it?”

“It was not enough,” said Father Vittorini. “He wished, I hear, to comment further on the problems of life on other worlds, and its effect on Christian thinking.”

Each of these words, precisely spoken, drove the two other men farther back in their chairs.

“You hear?” said Father Brian. “You haven’t read it yourself yet?”

“No, but I intend—”