По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

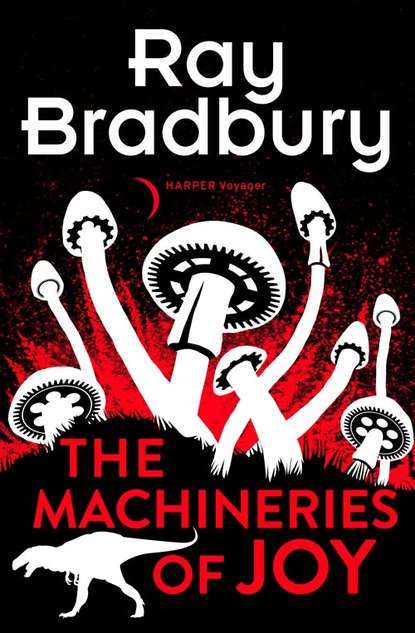

The Machineries of Joy

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You intend everything and mean worse. Sometimes, Father Vittorini, you do not talk, and I hate to say this, like a priest of the Mother Church at all.”

“I talk,” replied Vittorini, “like an Italian priest somehow caught and trying to preserve surface tension treading an ecclesiastical bog where I am outnumbered by a great herd of clerics named Shaughnessy and Nulty and Flannery that mill and stampede like caribou or bison every time I so much as whisper ‘papal bull.’”

“There is no doubt in my mind”—and here Father Brian squinted off in the general direction of the Vatican, itself—“that it was you, if you could’ve been there, might’ve put the Holy Father up to this whole space-travel monkeyshines.”

“I?”

“You! It’s you, is it not, certainly not us, that lugs in the magazines by the carload with the rocket ships on the shiny covers and the filthy green monsters with six eyes and seventeen gadgets chasing after half-draped females on some moon or other? You I hear late nights doing the countdowns from ten, nine, eight on down to one, in tandem with the beast TV, so we lie aching for the dread concussions to knock the fillings from our teeth. Between one Italian here and another at Castel Gandolfo, may God forgive me, you’ve managed to depress the entire Irish clergy!”

“Peace,” said Father Kelly at last, “both of you.”

“And peace it is, one way or another I’ll have it,” said Father Brian, taking the envelope from his pocket.

“Put that away,” said Father Kelly, sensing what must be in the envelope.

“Please give this to Pastor Sheldon for me.”

Father Brian rose heavily and peered about to find the door and some way out of the room. He was suddenly gone.

“Now see what you’ve done!” said Father Kelly.

Father Vittorini, truly shocked, had stopped eating. “But, Father, all along I thought it was an amiable squabble, with him putting on and me putting on, him playing it loud and me soft.”

“Well, you’ve played it too long, and the blasted fun turned serious!” said Kelly. “Ah, you don’t know William like I do. You’ve really torn him.”

“I’ll do my best to mend—”

“You’ll mend the seat of your pants! Get out of the way, this is my job now.” Father Kelly grabbed the envelope off the table and held it up to the light, “The X ray of a poor man’s soul. Ah, God.”

He hurried upstairs. “Father Brian?” he called. He slowed. “Father?” He tapped at the door. “William?”

In the breakfast room, alone once more, Father Vittorini remembered the last few flakes in his mouth. They now had no taste. It took him a long slow while to get them down.

It was only after lunch that Father Kelly cornered Father Brian in the dreary little garden behind the rectory and handed back the envelope.

“Willy, I want you to tear this up. I won’t have you quitting in the middle of the game. How long has all this gone on between you two?”

Father Brian sighed and held but did not rip the envelope. “It sort of crept upon us. It was me at first spelling the Irish writers and him pronouncing the Italian operas. Then me describing the Book of Kells in Dublin and him touring me through the Renaissance. Thank God for small favors, he didn’t discover the papal encyclical on the blasted space traveling sooner, or I’d have transferred myself to a monkery where the fathers keep silence as a vow. But even there, I fear, he’d follow and count down the Canaveral blastoffs in sign language. What a Devil’s advocate that man would make!”

“Father!”

“I’ll do penance for that later. It’s just this dark otter, this seal, he frolics with Church dogma as if it was a candy-striped bouncy ball. It’s all very well to have seals cavorting, but I say don’t mix them with the true fanatics, such as you and me! Excuse the pride, Father, but there does seem to be a variation on the true theme every time you get them piccolo players in amongst us harpers, and don’t you agree?”

“What an enigma, Will. We of the Church should be examples for others on how to get along.”

“Has anyone told Father Vittorini that? Let’s face it, the Italians are the Rotary of the Church. You couldn’t have trusted one of them to stay sober during the Last Supper.”

“I wonder if we Irish could?” mused Father Kelly.

“We’d wait until it was over, at least!”

“Well, now, are we priests or barbers? Do we stand here splitting hairs, or do we shave Vittorini close with his own razor? William, have you no plan?”

“Perhaps to call in a Baptist to mediate.”

“Be off with your Baptist! Have you researched the encyclical?”

“The encyclical?”

“Have you let grass grow since breakfast between your toes? You have! Let’s read that space-travel edict! Memorize it, get it pat, then counterattack the rocket man in his own territory! This way, to the library. What is it the youngsters cry these days? Five, four, three, two, one, blast off?”

“Or the rough equivalent.”

“Well, say the rough equivalent, then, man. And follow me!”

They met Pastor Sheldon, going into the library as he was coming out.

“It’s no use,” said the pastor, smiling, as he examined the fever in their faces. “You won’t find it in there.”

“Won’t find what in there?” Father Brian saw the pastor looking at the letter which was still glued to his fingers, and hid it away, fast. “Won’t find what, sir?”

“A rocket ship is a trifle too large for our small quarters,” said the pastor in a poor try at the enigmatic.

“Has the Italian bent your ear, then?” cried Father Kelly in dismay.

“No, but echoes have a way of ricocheting about the place. I came to do some checking myself.”

“Then,” gasped Brian with relief, “you’re on our side?”

Pastor Sheldon’s eyes became somewhat sad. “Is there a side to this, Fathers?”

They all moved into the little library room, where Father Brian and Father Kelly sat uncomfortably on the edges of the hard chairs. Pastor Sheldon remained standing, watchful of their discomfort.

“Now. Why are you afraid of Father Vittorini?”

“Afraid?” Father Brian seemed surprised at the word and cried softly, “It’s more like angry.”

“One leads to the other,” admitted Kelly. He continued, “You see, Pastor, it’s mostly a small town in Tuscany shunting stones at Meynooth, which is, as you know, a few miles out from Dublin.”

“I’m Irish,” said the pastor, patiently.

“So you are, Pastor, and all the more reason we can’t figure your great calm in this disaster,” said Father Brian.

“I’m California Irish,” said the pastor.

He let this sink in. When it had gone to the bottom, Father Brian groaned miserably. “Ah. We forgot.”

And he looked at the pastor and saw there the recent dark, the tan complexion of one who walked with his face like a sunflower to the sky, even here in Chicago, taking what little light and heat he could to sustain his color and being. Here stood a man with the figure, still, of a badminton and tennis player under his tunic, and with the firm lean hands of the handball expert. In the pulpit, by the look of his arms moving in the air, you could see him swimming under warm California skies.