По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

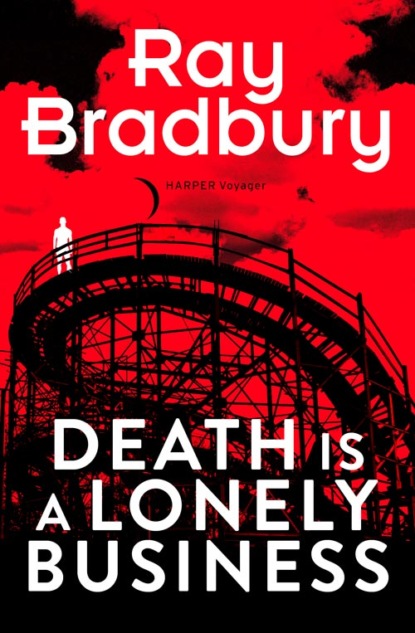

Death is a Lonely Business

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You sound like a sensitive child.” The old woman’s head sank, exhausted, and she shut her eyes. “They don’t make them that way any more.”

They never did, I thought.

“But,” she whispered, “you didn’t really come see me about the canaries—?”

“No,” I admitted. “It’s about that old man who rents from you—”

“He’s dead.”

Before I could speak, she went on, calmly, “I haven’t heard him in the downstairs kitchen since early yesterday. Last night, the silence told me. When you opened the door down there just now, I knew it was someone come to tell me all that’s bad.”

I’m sorry.

“Don’t be. I never saw him save at Christmas. The lady next door takes care of me, comes and rearranges me twice a day, and puts out the food. So he’s gone, is he? Did you know him well? Will there be a funeral? There’s fifty cents there on the bureau. Buy him a little bouquet.”

There was no money on the bureau. There was no bureau. I pretended that there was and pocketed some nonexistent money.

“You just come back in six months,” she whispered. “I’ll be well again. And the canaries will be on sale, and … you keep looking at the door! Must you go?”

“Yes’m,” I said, guiltily. “May I suggest—your front door’s unlocked.”

“Why, what in the world would anyone want with an old thing like me?” She lifted her head a final time.

Her eyes flashed. Her face ached with something beating behind the flesh to pull free.

“No one’ll ever come into this house, up those stairs,” she cried.

Her voice faded like a radio station beyond the hills. She was slowly tuning herself out as her eyelids lowered.

My God, I thought, she wants someone to come up and do her a dreadful favor!

Not me! I thought.

Her eyes sprang wide. Had I said it aloud?

“No,” she said, looking deep into my face. “You’re not him.”

“Who?”

“The one who stands outside my door. Every night.” She sighed. “But he never comes in. Why doesn’t he?”

She stopped like a clock. She still breathed, but she was waiting for me to go away.

I glanced over my shoulder.

The wind moved dust in the doorway like a mist, like someone waiting. The thing, the man, whatever, who came every night and stood in the hall.

I was in the way.

“Goodbye,” I said.

Silence.

I should have stayed, had tea, dinner, breakfast with her. But you can’t protect all of the people in all of the places all of the time, can you?

I waited at the door.

Goodbye.

Did she moan this in her old sleep? I only knew that her breath pushed me away.

Going downstairs I realized I still didn’t know the name of the old man who had drowned in a lion cage with a handful of train ticket confetti uncelebrated in each pocket.

I found his room. But that didn’t help.

His name wouldn’t be there, any more than he was.

Things are good at their beginnings. But how rarely in the history of men and small towns or big cities is the ending good.

Then, things fall apart. Things turn to fat. Things sprawl. The time gets out of joint. The milk sours. By night the wires on the high poles tell evil tales in the dripping mist. The water in the canals goes blind with scum. Flint, struck, gives no spark. Women, touched, give no warmth.

Summer is suddenly over.

Winter snows in your hidden bones.

Then it is time for the wall.

The wall of a little room, that is, where the shudders of the big red trains go by like nightmares turning you on your cold steel bed in the trembled basement of the Not So Royal Lost Canary Apartments, where the numbers have fallen off the front portico, and the street sign at the corner has been twisted north to east so that people, if they ever came to find you, would turn away forever on the wrong boulevard.

But meanwhile there’s mat wall near your bed to be read with your watered eyes or reached out to and never touched, it is too far away and too deep and too empty.

I knew that once I found the old man’s room, I would find that wall.

And I did.

The door, like all the doors in the house, was unlocked, waiting for wind or fog or some pale stranger to step in.

I stepped. I hesitated. Maybe I expected to find the old man’s X-ray imprint spread out there on his empty cot. His place, like the canary lady’s upstairs, looked like late in the day of a garage sale—for a nickel or a dime, everything had been stolen away.

There wasn’t even a toothbrush on the floor, or soap, or a washrag. The old man must have bathed in the sea once a day, brushed his teeth with seaweed each noon, washed his only shirt in the salt tide and lain beside it on the dunes while it dried, if and when the sun came out.

I moved forward like a deep sea diver. When you know someone is dead, his abandoned air holds back every motion you make, even your breathing.

I gasped.

I had guessed wrong.

For there his name was, on the wall. I almost fell, leaning down to squint.