По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

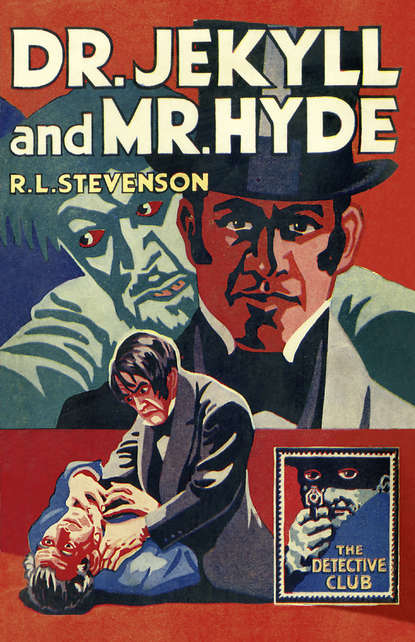

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#u9e73045a-a9ca-5e84-9ff2-251865965ac1)

AS a modest and self-effacing author who was initially convinced that ‘my fame will not last more than four years’, Robert Louis Stevenson would have been amazed at his subsequent great fame and renown. Celebrated as a brilliant essayist, novelist and children’s poet, in a literary career that lasted barely twenty years, he was also a master of finely wrought horror, culminating in his celebrated ‘shilling shocker’, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in 1886.

A tormented, guilt-ridden work, Jekyll and Hyde grew out of Stevenson’s early youth in Edinburgh during which he became obsessed by a long series of sequential dreams. In these nightmares he led a double life, working by day in a horrific surgery and roaming the streets of the old town by night. This existence only stopped when he was given a powerful opiate by his doctor. Today, when the control or change of personality by drugs is taken for granted, Stevenson’s premise has become far less fantastic.

Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson was born on 13 November 1850, changing his second name to ‘Louis’ at the age of eighteen. Most of the family on his father’s side were successful engineers, especially in the design of lighthouses.

In his early years, the young Robert was never able to tolerate his ‘respectable’ background, and became fascinated by the back streets of Edinburgh and the ‘dregs of humanity’ he found there. He also observed the dreadful changes directly caused by alcohol in his close friend Walter Ferrier.

Many dramatic stories of this era described horrifying mental disintegration resulting from drugs, opiates and the ‘demon drink’, notably Bram Stoker’s first serialised novel, The Primrose Path (1875), which incorporated touches of weird fantasy and allegory, ending with a grisly murder and suicide.

The young Stevenson’s first love was the beautiful Kate Drummond, but their marriage plans were quashed when his father threatened to stop his allowance. Robert gave in but never forgave himself when Kate had a breakdown and succumbed to a life of squalor.

During his youth, Stevenson read many ‘penny dreadfuls’ and other accounts of crime and murder (fact and fiction), and always held a keen interest in the supernatural and the uncanny ways in which the human brain can distort reality. His own short stories are often distinguished by psychological insight together with a deft handling of horror. Stevenson’s first ‘crawler’ (his own pet name for horror stories) was ‘The Body Snatcher’, written in 1881 and inspired by the notorious exploits of Burke and Hare. He shelved the story for three years ‘in a justifiable disgust, the tale being horrid’, but it eventually appeared in the Christmas number of the Pall Mall Gazette (1884).

Following soon after Stevenson’s enormous popular success with the adventure classic Treasure Island, ‘The Body Snatcher’ was widely advertised on posters, which were quickly suppressed by the police for being too lurid and shocking. He allegedly turned down his £40 fee, having such a low opinion of the story, but it has been widely reprinted and admired ever since, and appears again in this new Detective Club edition.

Three of Stevenson’s other outstanding short stories written around the same time, ‘Thrawn Janet’, ‘Markheim’ and ‘Olalla’, all appeared in his collection The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables (1887). ‘Thrawn Janet’ (1881), Stevenson’s very own favourite, is a tale of satanic possession, told in Scots vernacular; the ghostly stranger in ‘Markheim’ (1884) is revealed to be a murderer’s good conscience, an important step toward the ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ allegory; and ‘Olalla’ (1885) is another memorable story of a diseased mind.

After travelling to California where he married Fanny Osbourne, the couple returned to Europe, eventually settling at Bournemouth in 1884 for three years. Stevenson continued to write for many periodicals and produced a long line of successful books including travelogues, essays, two collections of New Arabian Nights (1882/1885), Treasure Island (1883) and A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885).

The original draft of Jekyll and Hyde was written at great speed in three days (after a series of vivid nightmares) at Bournemouth in 1885. Stevenson then allegedly burned the manuscript and rewrote it in another three days after his wife objected that he had omitted the vital allegory. Relating the unique scientific experiments and confession of Henry Jekyll, a successful London physician, the story is told from the oblique perspective of his friend Dr. Hastie Lanyon, his lawyer Gabriel John Utterson, and Utterson’s cousin Richard Enfield.

In fairy tales and classical mythology, people often metamorphose into beasts and back again, but it was Stevenson who first conceived the process by which one human being turns into another, both spiritually and physically. His Victorian readers were fascinated by the idea of the total incarnation of a good man’s evil subconscious into a Caliban figure. Through the portrayal of Jekyll suffering from the suppression of his natural instincts, Stevenson was attacking the rampant hypocrisy of highly respectable and upright Christian ‘ideal husbands’ who led double lives.

Stevenson had examined this theme in his early play, Deacon Brodie; or The Double Life (1880; co-written with his friend W. E. Henley), based on the infamous exploits of a highly esteemed Edinburgh dignitary who headed a gang of thieves and murderers in the 1780s, and was later hanged for his crimes. Although Stevenson’s story is set in London, it remains very close to the atmosphere of Edinburgh.

The first edition of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was originally scheduled to appear at Christmas 1885, but was then postponed for two weeks with the date in every copy amended by ink to ‘1886’. It was published at the cheap price of one shilling (perfectly fitting the popular ‘shilling shocker’ format) by Longmans, who felt it was a work that should be within everyone’s reach.

In a matter of months, over 40,000 copies were reportedly sold, and there were several simultaneous editions in America. The story was widely used as a parable and moral text in pulpits throughout the land, and made the subject of leading articles in religious newspapers. One eminent critic, J. A. Symonds, wrote: ‘I do not know whether anyone has the right to scrutinise the abysmal depths of personality, but the art is burning and intense.’

Jekyll and Hyde was dramatised on the stage in 1887 by T. R. Sullivan, and Richard Mansfield made a very successful career in the dual roles, notably during 1888, coinciding with the ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders in London. The most successful and powerful early screen performers of Jekyll and Hyde were John Barrymore (1921), Fredric March (1931; Best Actor Academy Award), and Spencer Tracy (1941).

In many ways, Stevenson’s The Master of Ballantrae (1889) is an equally spine-chilling novel, another evocative story of dual personalities, with the two Durie brothers standing for love and hate, good and evil. Henry, the kind brother, is gradually drained of his goodness by James, the incarnation of fascinating evil. As with the earlier story, Hyde conquers Jekyll.

In search of relief for his poor health, Stevenson sailed with Fanny to America and the Pacific Ocean, and settled in Samoa in 1890, where he died four years later on 3 December 1894, leaving a great legacy of literary works which have remained in print ever since.

After 1886 there were several unsatisfactory attempts to explain the Jekyll and Hyde mystery by various unknown or anonymous writers, which are best forgotten. A very early example was The Untold Sequel of the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde which claimed, very unconvincingly, that Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde were really two different men, with no metamorphosis involved. It was published in 1890 by Pinckney in Boston without an author byline, with readers presumably thinking that their fifteen cents were buying a sequel by Stevenson himself. The story was subsequently catalogued as having been written by one Francis H. Little, and one assumes that Stevenson never knew about it.

Various pastiches written during the twentieth century have often been more successful. One of the best examples is ‘Dr Jekyl’, a tale by the American author Robert J. McLaughlin, in which the case is solved by Arnold Stone, a detective of Holmes/Poirot-like ingenuity. In spite of the title, ‘Dr Jekyl’ is a story of a mysterious dual identity which recalls Stevenson’s The Master of Ballantrae with the return of a long-lost prodigal brother. ‘Dr Jekyl’ originally appeared with three other Arnold Stone mysteries in McLaughlin’s collection A Horsehair Santa Claus, published by Christopher in Boston in 1931.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (dropping Strange Caseof from its title) joined the ranks of the burgeoning Collins Pocket Classics in the 1920s as number 276 in the series, priced two shillings and with illustrations by Frank Gillet. An unillustrated sixpenny edition followed in September 1929, one of the first dozen titles in the new Detective Story Club imprint, with an essay by John Inglisham to help bulk up the slim volume.

Robert Louis Stevenson has always been loved and admired by countless readers and critics for ‘the excitement, the fierce joy, the delight in strangeness, the pleasure in deep and dark adventures’ found in his classic stories and, without doubt, he created some of the most horribly unforgettable characters in literature: Long John Silver, Ebenezer Balfour, James Durie of Ballantrae and, above all, Mr. Edward Hyde.

RICHARD DALBY

July 2015

STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (#u9e73045a-a9ca-5e84-9ff2-251865965ac1)

TO

KATHARINE DE MATTOS

It’s ill to loose the bands that God decreed to bind;

Still will we be the children of the heather and the wind.

Far away from home, O it’s still for you and me

That the broom is blowing bonnie in the north countrie.

CHAPTER I (#ulink_dd376626-2e5a-5567-9956-76a2b49c84e5)

STORY OF THE DOOR (#ulink_dd376626-2e5a-5567-9956-76a2b49c84e5)

MR. UTTERSON the lawyer was a man of a rugged countenance, that was never lighted by a smile; cold, scanty and embarrassed in discourse; backward in sentiment; lean, long, dusty, dreary, and yet somehow lovable. At friendly meetings, and when the wine was to his taste, something eminently human beaconed from his eye; something indeed which never found its way into his talk, but which spoke not only in these silent symbols of the after-dinner face, but more often and loudly in the acts of his life. He was austere with himself; drank gin when he was alone, to mortify a taste for vintages; and though he enjoyed the theatre, had not crossed the doors of one for twenty years. But he had an approved tolerance for others; sometimes wondering, almost with envy, at the high pressure of spirits involved in their misdeeds; and in any extremity inclined to help rather than to reprove. ‘I incline to Cain’s heresy,’ he used to say quaintly: ‘I let my brother go to the devil in his own way.’ In this character, it was frequently his fortune to be the last reputable acquaintance and the last good influence in the lives of down-going men. And to such as these, so long as they came about his chambers, he never marked a shade of change in his demeanour.

No doubt the feat was easy to Mr. Utterson; for he was undemonstrative at the best, and even his friendships seemed to be founded in a similar catholicity of good-nature. It is the mark of a modest man to accept his friendly circle ready made from the hands of opportunity; and that was the lawyer’s way. His friends were those of his own blood, or those whom he had known the longest; his affections, like ivy, were the growth of time, they implied no aptness in the object. Hence, no doubt, the bond that united him to Mr. Richard Enfield, his distant kinsman, the well-known man about town. It was a nut to crack for many, what these two could see in each other, or what subject they could find in common. It was reported by those who encountered them in their Sunday walks, that they said nothing, looked singularly dull, and would hail with obvious relief the appearance of a friend. For all that, the two men put the greatest store by these excursions, counted them the chief jewel of each week, and not only set aside occasions of pleasure, but even resisted the calls of business, that they might enjoy them uninterrupted.

It chanced on one of these rambles that their way led them down a by-street in a busy quarter of London. The street was small and what is called quiet, but it drove a thriving trade on the week-days. The inhabitants were all doing well, it seemed, and all emulously hoping to do better still, and laying out the surplus of their gains in coquetry; so that the shop fronts stood along that thoroughfare with an air of invitation, like rows of smiling saleswomen. Even on Sunday, when it veiled its more florid charms and lay comparatively empty of passage, the street shone out in contrast to its dingy neighbourhood, like a fire in a forest; and with its freshly painted shutters, well-polished brasses, and general cleanliness and gaiety of note, instantly caught and pleased the eye of the passenger.

Two doors from one corner, on the left hand going east, the line was broken by the entry of a court; and just at that point, a certain sinister block of building thrust forward its gable on the street. It was two stories high; showed no window, nothing but a door on the lower story and a blind forehead of discoloured wall on the upper; and bore in every feature, the marks of prolonged and sordid negligence. The door, which was equipped with neither bell nor knocker, was blistered and distained. Tramps slouched into the recess and struck matches on the panels; children kept shop upon the steps; the schoolboy had tried his knife on the mouldings; and for close on a generation, no one had appeared to drive away these random visitors or to repair their ravages.

Mr. Enfield and the lawyer were on the other side of the by-street; but when they came abreast of the entry, the former lifted up his cane and pointed.

‘Did you ever remark that door?’ he asked; and when his companion had replied in the affirmative, ‘It is connected in my mind,’ added he, ‘with a very odd story.’

‘Indeed,’ said Mr. Utterson, with a slight change of voice, ‘and what was that?’

‘Well, it was this way,’ returned Mr. Enfield: ‘I was coming home from some place at the end of the world, about three o’clock of a black winter morning, and my way lay through a part of town where there was literally nothing to be seen but lamps. Street after street, and all the folks asleep—street after street, all lighted up as if for a procession and all as empty as a church—till at last I got into that state of mind when a man listens and listens and begins to long for the sight of a policeman. All at once, I saw two figures: one a little man who was stumping along eastward at a good walk, and the other a girl of maybe eight or ten who was running as hard as she was able down a cross street. Well, sir, the two ran into one another naturally enough at the corner; and then came the horrible part of the thing; for the man trampled calmly over the child’s body and left her screaming on the ground. It sounds nothing to hear, but it was hellish to see. It wasn’t like a man; it was like some damned Juggernaut. I gave a view halloa, took to my heels, collared my gentleman, and brought him back to where there was already quite a group about the screaming child. He was perfectly cool and made no resistance, but gave me one look, so ugly that it brought out the sweat on me like running. The people who had turned out were the girl’s own family; and pretty soon, the doctor, for whom she had been sent, put in his appearance. Well, the child was not much the worse, more frightened, according to the Sawbones; and there you might have supposed would be an end to it. But there was one curious circumstance. I had taken a loathing to my gentleman at first sight. So had the child’s family, which was only natural. But the doctor’s case was what struck me. He was the usual cut-and-dry apothecary, of no particular age and colour, with a strong Edinburgh accent, and about as emotional as a bagpipe. Well, sir, he was like the rest of us; every time he looked at my prisoner, I saw that Sawbones turn sick and white with the desire to kill him. I knew what was in his mind, just as he knew what was in mine; and killing being out of the question, we did the next best. We told the man we could and would make such a scandal out of this, as should make his name stink from one end of London to the other. If he had any friends or any credit, we undertook that he should lose them. And all the time, as we were pitching it in red hot, we were keeping the women off him as best we could, for they were as wild as harpies. I never saw a circle of such hateful faces; and there was the man in the middle, with a kind of black, sneering coolness—frightened too, I could see that—but carrying it off, sir, really like Satan. “If you choose to make capital out of this accident,” said he, “I am naturally helpless. No gentleman but wishes to avoid a scene,” says he. “Name your figure.” Well, we screwed him up to a hundred pounds for the child’s family; he would have clearly liked to stick out; but there was something about the lot of us that meant mischief, and at last he struck. The next thing was to get the money; and where do you think he carried us but to that place with the door?—whipped out a key, went in, and presently came back with the matter of ten pounds in gold and a cheque for the balance on Coutts’s, drawn payable to bearer and signed with a name that I can’t mention, though it’s one of the points of my story, but it was a name at least very well known and often printed. The figure was stiff; but the signature was good for more than that, if it was only genuine. I took the liberty of pointing out to my gentleman that the whole business looked apocryphal, and that a man does not, in real life, walk into a cellar door at four in the morning and come out of it with another man’s cheque for close upon a hundred pounds. But he was quite easy and sneering. “Set your mind at rest,” says he, “I will stay with you till the banks open and cash the cheque myself.” So we all set off, the doctor, and the child’s father, and our friend and myself, and passed the rest of the night in my chambers; and next day, when we had breakfasted, went in a body to the bank. I gave in the check myself, and said I had every reason to believe it was a forgery. Not a bit of it. The cheque was genuine.’

‘Tut-tut!’ said Mr. Utterson.

‘I see you feel as I do,’ said Mr. Enfield. ‘Yes, it’s a bad story. For my man was a fellow that nobody could have to do with, a really damnable man; and the person that drew the cheque is the very pink of the proprieties, celebrated too, and (what makes it worse) one of your fellows who do what they call good. Blackmail, I suppose; an honest man paying through the nose for some of the capers of his youth. Black-Mail House is what I call that place with the door, in consequence. Though even that, you know, is far from explaining all,’ he added; and with the words fell into a vein of musing.

From this he was recalled by Mr. Utterson asking rather suddenly: ‘And you don’t know if the drawer of the cheque lives there?’

‘A likely place, isn’t it?’ returned Mr. Enfield. ‘But I happen to have noticed his address; he lives in some square or other.’

‘And you never asked about—the place with the door?’ said Mr. Utterson.