По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

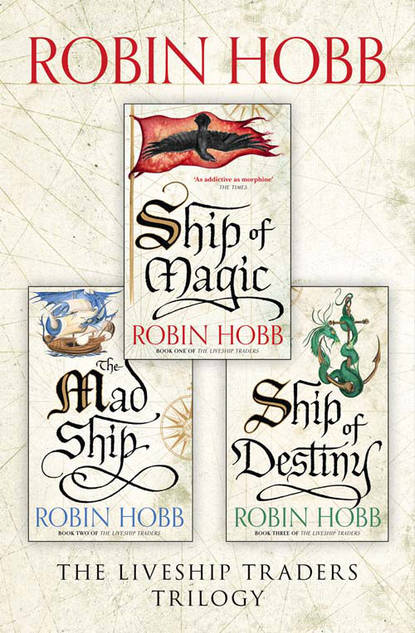

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Oh, Mother,’ she said, and moved towards her, but her mother flapped her hands at her in refusal. Althea stopped instantly. Ronica Vestrit had never been one for tearful embraces and weeping on shoulders. She might be bowed by her sorrow, but she had not surrendered to it.

‘Go and see your father,’ she told Althea. ‘He’s been asking for you, near hourly. I must speak to Kyle. There are arrangements to be made, and not much time, I fear. Go in to him, now. Go.’ She gave Althea two quick pats on the arm and then hastened past her. Althea heard the pattering of her shoes and the rustling of her skirts as she hurried away down the hall. Althea glanced once after her and then pushed open the door of her father’s bedchamber.

This was not a familiar room to her. As a small child, it had been forbidden to her. When her father had been home from voyages, he and her mother had spent time there together, and Althea had resented the mornings when she was not allowed to intrude on their rest. When she had grown old enough to understand why her parents might value their time alone together on his brief visits home, she had willingly avoided the room. Still, she recalled the room as a large, bright chamber with tall windows, furnished sumptuously with exotic furniture and fabrics from many voyages. The white walls had displayed feather fans and shell masks, beaded tapestries and hammered copper landscapes. The bed had a headboard of carved teak, and in winter the thick mattress was always mounded with feather comforters and fur throws. During the summers there had been vases of flowers by the bedside and cool cotton sheets scented with roses.

The door opened onto dimness. Attar of roses had been vanquished by the thick sour odour of the sickroom and the stinging scent of medicines. The windows were closed, the curtains drawn against the day’s brightness. Althea moved uncertainly into the room as her eyes adjusted to the darkness. ‘Papa?’ she asked hesitantly of the still, mounded bed. There was no reply.

She went to a window and pushed back the heavy brocaded curtains to admit the slanting afternoon light. A corner of the light fell on the bed, lighting a fleshless yellow hand resting upon the covers. It reminded her of the gaunt, curled talons of a dead bird. She crossed the room to the bedside chair and took what she knew was her mother’s post there. Despite her love for her father, she felt a moment’s revulsion as she took that limp hand in her own. Muscle and callous had fled that hand. She leaned forward to look into his face. ‘Papa?’ she asked again.

He was already dead. Or so she thought from that first look into his face. Then she heard the rasp of an indrawn breath. ‘Althea,’ he breathed out in a voice that rattled with mucus. His gummy eyelids pried themselves open. The sharp black glance was gone. These eyes were sunken and bloodshot, the whites yellowed. It took him a moment to find her. He gazed at her and she desperately tried to smooth the horror from her face.

‘Papa, I’m home,’ she told him with false brightness, as if that could make some difference to him.

His hand twitched feebly in hers, then his eyes slid shut again. ‘I’m dying,’ he told her in despair and anger.

‘Oh, Papa, no, you’ll get better, you’ll…’

‘Shut up.’ It was no more than a whisper, but the command came from both her captain and her father. ‘Only one thing that matters. Get me to Vivacia. Got to die on her decks. Got to.’

‘I know,’ she said. The pain that had just started unfolding in her heart was suddenly stilled. There was no time for it, just now. ‘I’ll get things ready.’

‘Right now,’ he warned her. His whisper sounded gurgly, drowning. A wave of despair washed over her, but she righted herself.

‘I won’t fail you,’ she promised him. His hand twitched again, and fell free of hers. ‘I’ll go right now.’

As she stood he choked, then managed to gag out, ‘Althea!’

She halted where she stood. He strangled for a bit, then gasped in a breath. ‘Keffria and her children. They’re not like you.’ He took another frantic breath. ‘I had to provide for them. I had to.’ He fought for more breath for speaking, but could not find any.

‘Of course you did. You provided well for all of us. Don’t worry about that now. Everything is going to be fine. I promise.’

She had left the room and was halfway down the hall before she heard what she had said to him. What had she meant by that promise? That she would make sure he died on the liveship he had commanded so long! It was an odd definition of fine. Then, with unshakeable certainty, she knew that when her time came to die, if she could die on the Vivacia’s decks, everything would be fine for her, too. She rubbed at her face, feeling as if she were just waking up. Her cheeks were wet. She was weeping. No time for that, just now. No time to feel, no time to weep.

As she hurried out the door into the blinding sunlight, she all but ran into a knot of people clustered there. She blinked for a moment, and they suddenly resolved into her mother and Kyle and Keffria and the children. They stared at her in silence. For a moment she returned that stricken gaze. Then, ‘I’m going down to get the ship ready,’ she told them all. ‘Give me an hour. Then bring Papa down.’

Kyle frowned darkly and made as if to speak, but before he could her mother nodded and dully said, ‘Do so.’ Her voice closed down on the words, and Althea watched her struggle to speak through a throat gone tight with grief. ‘Hurry,’ she managed at last, and Althea nodded. She set off on foot down the drive. In the time it took a runner to get to town and send a shimshay back for her, she could be almost to the ship.

‘At least send a servant with her!’ she heard Kyle exclaim angrily behind her, and more softly her mother replied, ‘No. Let her go, let her go. There’s no time to be concerned about appearances now. I know. Come help me prepare a litter for him.’

By the time she reached the docks, her dress was drenched in sweat. She cursed the fate that made her a woman doomed to wear such attire. An instant later she was thanking the same Sa she had been rebuking, for a space had opened up on the Tax Docks, and the Vivacia was being edged into place there. She waited impatiently, and then hiked up her skirts and leapt from the dock to her decks even as the ship was being tied up.

Gantry, Kyle’s first mate, stood on the foredeck, hands on hips. He started at the sight of her. He’d recently been in some kind of a tussle. The side of his face had swelled and just begun to purple. She dismissed it from her mind; it was the mate’s job to keep the crew in line and the first day back in port could be a contentious one. Liberty was so close, and shore and deck crews did not always mingle well. But the scowl he wore seemed to be directed at her. ‘Mistress Althea. What do you here?’ He sounded outraged.

At any other time, she’d have afforded the time to be offended at his tone. But now she simply said, ‘My father is dying. I’ve come to prepare the ship to receive him.’

He looked no less hostile, but there was deference in his tone as he asked, ‘What do you wish done?’

She lifted her hands to her temples. When her grandfather had died, what had been done? It had been so long ago, but she was supposed to know about these things. She took a deep calming breath, then crouched down suddenly to set her hand flat upon the deck. Vivacia. So soon to quicken. ‘We need to set up a pavilion on deck. Over there. Canvas is fine, and set it so the breezes can cool him.’

‘What’s wrong with putting him in his cabin?’ Gantry demanded.

‘That’s not how it’s done,’ Althea said tersely. ‘He needs to be out here, on the deck, with nothing between him and the ship. There must be room for all the family to witness. Set up some plank benches for those who keep the death watch.’

‘I’ve got a ship to unload,’ Gantry declared abruptly. ‘Some of the cargo is perishable. It’s got to be taken off. How is my crew to get that done, and set up this pavilion and work around a deck full of folk?’ This he demanded of her, in full view and hearing of the entire crew. There was something of challenge in his tone.

Althea stared at him, wondering what possessed the man to argue with her just now. Couldn’t he see how important this was? No, probably not. He was one of Kyle’s choosing; he knew nothing of the quickening of a liveship. Almost as if her father stood at her shoulder, she heard her voice mouth the familiar command he’d always given Brashen in difficult times. She straightened her spine.

‘Cope,’ she ordered him succinctly. She glanced about the deck. Sailors had paused in their tasks to follow this interchange. In some faces she saw sympathy and understanding, in others only the avidity with which men watch a battle of wills. She put a touch of snarl in her voice. ‘If you can’t deal with it, put Brashen in charge. He’d find it no challenge.’ She started to turn away, then turned back. ‘In fact, that’s the best solution. Put Brashen in charge of the setting up for Captain Vestrit. He’s his first mate, that’s fitting. You see to the unloading of your captain’s cargo.’

‘On board, there can be but one captain,’ Gantry observed. He looked aside as if not truly speaking to her, but she chose to reply anyway.

‘That’s correct, sailor. And when Captain Vestrit is aboard, there is but one captain. I doubt you’ll find many men on board to question that.’ She swung her eyes away from him to the ship’s carpenter. As much as she currently disliked the man, his loyalty to her father had always been absolute. She caught his glance and addressed him. ‘Assist Brashen in any way he requires. Be quick. My father will arrive here soon. If this is the last time he sets foot on board, I’d like him to see the Vivacia ship-shape and the crew busy.’

This simple appeal was all she needed. Sudden understanding swept over his face, and the look he gave to the rest of the crew quickly spread the realization. This was real, this was urgent. The man they had served under, some for over two decades, was coming here to die. He’d often bragged that his was the best hand-picked crew to sail out of Bingtown; Sa knew he paid them better than they’d have made on any other vessel.

‘I’ll find Brashen,’ the carpenter assured her and strode off with purpose in his walk. Gantry took a breath as if to call him back. Instead, he paused for just an instant, and then began barking out orders for the continued unloading of the ship. He turned just enough that Althea was not in his direct line of sight. He had dismissed her. She had a reflex of anger before she recalled she had no time for his petty insolence just now. Her father was dying.

She went to the sailmaker to order out a length of clean canvas. When she came back up on deck, Brashen was there talking with the ship’s carpenter. He was gesticulating at the rigging as they discussed how they’d hang the canvas. When he turned to glance at her, she saw a swollen knot above his left eye. So it was he the mate had tangled with. Well, whatever it had been, it had been sorted out in the usual way.

There was little more for her to do except stand about and watch. She’d given Brashen command of the situation and he’d accepted it. One thing she had learned from her father: once you put a man in charge of something, you didn’t ride him while he did the task. Nor did she wish Gantry to grumble that she stood about and got in the way. With no where else to gracefully go, she went to her cabin.

It had been stripped, save for the painting of the Vivacia. The sight of the empty shelves near wrenched her heart from her chest. All her possessions had been neatly and tightly stowed in several open crates in the room. Planking, nails and a hammer were on the deck. This, then, had been the task Brashen had been called away from. She sat down on the ticking mattress on her bunk and stared at the crates. Some industrious creature inside her wanted to crouch down and hammer the planks into place. Defiance bid her unpack her things and put them in their rightful places. She was caught between these things, and did nothing for a time.

Then with a shocking suddenness, grief throttled her. Her sobs could not come up, she couldn’t even take a breath for the tightness in her throat. Her need to cry was a terrible squeezing pain that literally suffocated her. She sat on her bunk, mouth open and strangling. When she finally got a breath of air into her lungs, she could only sob. Tears streamed down her face, and she had no handkerchief, nothing but her sleeve or her skirts, and what kind of a terrible heartless person was she that she could even think of handkerchiefs at a time like this? She leaned her head into her hands and finally allowed herself simply to weep.

They moved off, clucking and muttering to one another like a flock of chickens. Wintrow was forced to trail after them. He didn’t know what else to do. He had been in Bingtown for five days now, and still had no idea why they had summoned him home. His grandfather was dying; of course he knew that, but he could scarcely see what they expected him to do about it, or even how they expected him to react.

Dying, the old man was even more daunting than he had been in life. When Wintrow had been a boy, it had been the sheer force of the man’s life-strength that had cowed him. Now it was the blackness of dwindling death that seeped out from him and emptied its darkness into the room. On the ship home, Wintrow had made a strong resolve that he would get to know something of his grandfather before the old man died. But it was too late for that. In these last weeks, all that Ephron Vestrit possessed of himself had been focused into keeping a grip on life. He had held on grimly to every breath, and it was not for the sake of his grandson’s presence. No. He awaited only the return of his ship.

Not that Wintrow had had much time with his grandfather. When he had first arrived, his mother had scarcely given him time to wash the dust of travel from his face and hands before she ushered him in and presented him. Disoriented after his sea voyage and the rattling trip through the hot and bustling city streets, he had barely been able to grasp that this short, dark-haired woman was the Mama he had once looked up to. The room she hurried him into had been curtained against the day’s heat and light. Inside was a woman in a chair beside a bed. The room smelled sour and close, and it was all he could do to stand still when the woman rose and embraced him. She clutched at his arm as soon as his mother released her grip on him, and pulled him towards the bedside.

‘Ephron,’ she had said quietly. ‘Ephron, Wintrow is here.’

And in the bed, a shape stirred and coughed and then mumbled what might have been an acknowledgement. He stood there, shackled by his grandmother’s grip on his wrist, and only belatedly offered a ‘Hello, Grandfather. I’ve come home to visit.’

If the old man had heard him at all, he hadn’t bothered with a reply. After a few moments, his grandfather had coughed again and then queried hoarsely, ‘Ship?’

‘No. Not yet,’ his grandmother replied gently.

They had stood there a while longer. Then, when the old man made no more movement and took no further notice of them, his grandmother said, ‘I think he wants to rest now, Wintrow. I’ll send for you later when he’s feeling a bit better.’

That time had not come. Now his father was home, and the news of Ephron Vestrit’s imminent death seemed to be all his mind could grasp. He had glanced at Wintrow over his mother’s shoulder as he embraced her. His eyes widened briefly and he nodded at his eldest son, but then his Mother Keffria began to pour out her torrent of bad news and all their complications. Wintrow stood apart, like a stranger, as first his sister Malta and then his younger brother Selden welcomed their father with a hug. At last there had been a pause in Keffria’s lament, and he stepped forward, to first bow and then grip hands with his father.

‘So. My son the priest,’ his father greeted him, and Wintrow could still not decide if there had been a breath of derision in those words. The next did not surprise him. ‘Your little sister is taller than you are. And why are you wearing a robe like a woman?’

‘Kyle!’ his mother rebuked her husband, but he had turned away from Wintrow without awaiting a reply.

Now, following his aunt’s departure, he trailed into the house behind them. The adults were already discussing the best ways of moving Ephron down to the ship, and what must be taken or brought down later. The children, Malta and Selden, followed, trying vainly to ask a string of questions of their mother and continually being shushed by their grandmother. And Wintrow trailed after all, feeling neither adult nor child, nor truly a part of this emotional carnival. On the journey here, he had realized he did not know what to expect. And ever since he had arrived, that feeling had increased. For the first day, most of his conversations had been with his mother, and had consisted of either her exclamations over how thin he was, or fond remembrances and reminiscing that inevitably began with, ‘I don’t suppose you remember this, but…’ Malta, once so close to him as to seem almost his shadow, now resented him for coming home and claiming any of their mother’s attention. She did not speak to him but about him, making stinging observations when their mother was out of earshot, ostensibly to the servants or Selden. It did not help that at twelve she was taller than he was, and already looking more like a woman than he did a man. No one would have suspected he was the elder. Selden, scarcely more than a baby when he had left, now dismissed him as a visiting relative, one scarcely worth getting to know, as he would doubtless soon be leaving. Wintrow fervently hoped Selden was right. He knew it was not worthy to long for his grandfather to die and simply get it over with so he could return to his monastery and his life, but he also knew that to deny the thought would only be another sort of lie.