По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

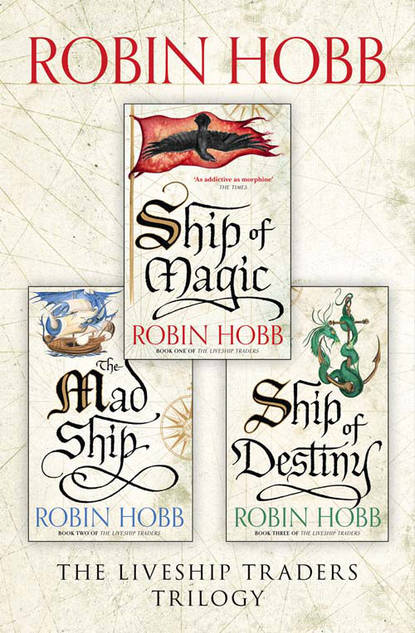

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It will have to be rushed,’ the man pointed out brusquely.

Wintrow skipped the prayers. He skipped the preparations, he skipped the soothing words designed to ready her mind and spirit. He simply stood and put his hands on her. He positioned his fingers on the sides of her neck, spreading them until each one found its proper point. ‘This is not death,’ he assured her. ‘I but free you from the distractions of this world so that your soul may prepare itself for the next. Do you assent to this?’

She nodded, a slow movement of her head.

He accepted her consent. He drew a slow, deep, breath, aligning himself with her. He reached inside himself, to the neglected budding of his priesthood. He had never done this by himself. He had never been fully initiated into the mysteries of it. But the mechanics he knew, and those at least he could give her. He noticed in passing that the man stood with his body blocking the broker’s view and kept watch over his shoulder. The other slaves clustered close around them, to hide what they did from passing traffic. ‘Hurry,’ Lem urged Wintrow again.

He pressed lightly on the points his fingers had unerringly chosen. The pressure would banish fear, would block pain while he spoke to her. As long as he pressed, she must listen and believe his words. He gave her body to her first. ‘To you, now, the beating of your heart, the pumping of air into your lungs. To you the seeing with your eyes, the hearing with your ears, the tasting of your mouth, the feeling of all your flesh. All these things do I trust to your own control now, that you may command them to be or not to be. All these things, I give back to you, that you may prepare yourself for death with a clear mind. The comfort of Sa I offer you, that you may offer it to others.’ He saw a shade of doubt in her eyes still. He helped her realize her own power. ‘Say to me, “I feel no cold”.’

‘I feel no cold,’ she faintly echoed.

‘Say to me, “the pain is no more”.’

‘The pain is no more.’ The words were soft as a sigh, but as she spoke them, lines eased from her face. She was younger than he had thought. She looked up at Lem and smiled at him. ‘The pain is gone,’ she said without prompting.

Wintrow took his hands away, but stood close still. She rested her head on Lem’s chest. ‘I love you,’ she said simply. ‘You are all that has made this life bearable. Thank you.’ She took a breath that came out as a sigh. ‘Thank the others for me. For the warmth of their bodies, for doing more that my less might not be noticed. Thank them…’

Her words trailed off and Wintrow saw Sa blossoming in her face. The travails of this world were already fading from her mind. She smiled, a smile as simple as a babe’s. ‘See how beautiful the clouds are today, my love. The white against the grey. Do you see them?’

As simply as that. Unchained from her pain, her spirit turned to contemplation of beauty. Wintrow had witnessed it before but it never ceased to amaze him. Once a person had realized death, if they could turn aside from pain they immediately turned toward wonder and Sa. It took both steps, Wintrow knew that. If a person had not accepted death as a reality, the touch could be refused. Some accepted death and the touch, but could not let go of their pain. They clung to it as a final vestige of life. But Cala had let go easily, so easily that Wintrow knew she had been longing to let go for a long time.

He stood quietly by and did not speak. Nor did he listen to the exact words she spoke to Lem. Tears coursed down Lem’s cheeks, over the scars of a hard life and the embedded dyes of his slave-tattoo. They dripped from his roughly shaven chin. He said nothing, and Wintrow purposely did not hear the content of Cala’s words. He listened to the tone instead and knew that she spoke of love and life and light. Blood still moved in a slow red trickle down her bare leg. He saw her head loll on her shoulder as she weakened, but the smile did not leave her face. She had been closer to death than he had guessed; her stoic demeanour had deceived him. She would be gone soon. He was glad he had been able to offer her and Lem this peaceful parting.

‘Hey!’ A bat jabbed him in the small of his back. ‘What are you doing?’

The slave-broker gave Wintrow no time to answer. Instead he pushed the boy aside, dealing him a bruising jab to the short ribs as he did so. It knocked the wind out of his lungs and for a moment, all he could do was curl over his offended midsection, gasping. The broker stepped boldly into the midst of his coffle, to snarl at Lem and Cala. ‘Get away from her,’ he spat at Lem. ‘What are you trying to do, get her pregnant again, right here in the middle of the street? I just got rid of the last one.’ Foolishly, he reached to grab Cala’s unresisting shoulder. He jerked at the woman but Lem held her fast even as he uttered a roar of outrage. Wintrow would have recoiled from the look in his eyes alone, but the slave-broker snapped Lem in the face with the small bat, a practised, effortless movement. The skin high on Lem’s cheek split and blood flowed down his face. ‘Let go!’ the broker commanded him at the same time. Big as the slave was, the sudden blow and pain half-stunned him. The broker snatched Cala from his embrace, and let her fall sprawling into the bloody dirt. She fell bonelessly, wordlessly, and lay where she had bled, staring beatifically up at the sky. Wintrow’s experienced eye told him that in reality she saw nothing at all. She had chosen to stop. As he watched, her breath grew shallower and shallower. ‘Sa’s peace to you,’ he managed to whisper in a strained voice.

The broker turned on him. ‘You’ve killed her, you idiot! She had at least another day’s work in her!’ He snapped the bat at Wintrow, a sharply stinging blow to the shoulder that broke the skin and bruised the flesh without breaking bones. From the point of his shoulder down, pain flashed through his arm, followed by numbness. Indeed, a well-practised gesture, some part of him decided as he yelped and sprang back. He stumbled into one of the other hobbled slaves, who pushed him casually aside. They were all closing on the broker and suddenly his nasty little bat looked like a puny and foolish weapon. Wintrow felt his gorge rise; they would beat him to death, they’d jelly his bones.

But the slave-broker was an agile little man who loved his work and excelled at it. Lively as a frisking puppy, he spun about and snapped out with his bat, flick, flick, flick. At each blow, his bat found slave-flesh, and a man fell back. He was adept at dealing out pain that disabled without damaging. He was not so cautious with Lem, however. The moment the big man moved, he struck him again, a sharp snap of the bat across his belly. Lem folded up over it, his eyes bulging from their sockets.

And meanwhile, in the slave-market, the passing traffic continued. A raised eyebrow or two at this unruly coffle, but what did one expect of map-faces and those who mongered them? Folk stepped well wide of them and continued on their way. No use to call to them for help, to protest he was not a slave. Wintrow doubted that any of them would care.

While Lem gagged up bile, the broker casually unlocked the blood-caked fetters from Cala’s ankles. He shook them clear of her dead feet, then glared at Wintrow. ‘By all rights, I should clap these on you!’ he snarled. ‘You’ve cost me a slave, and a day’s wages, if I’m not mistaken. And I am not, see, there goes my customer. He’ll want nothing to do with this coffle, after they’ve shown such bad temperament.’ He pointed the bat after his fleeing prospect. ‘Well. No work, no food, my charmers.’

The little man’s manner was so acridly pleasant, Wintrow could not believe his ears. ‘A woman is dead, and it is your fault!’ he pointed out to the man. ‘You poisoned her to shake loose a child, but it killed her as well. Murder twice is upon you!’ He tried to rise, but his whole arm was still numb from the earlier blow, as was his belly. He shifted to his knees to try to get up. The little man casually kicked him down again.

‘Such words, such words, from such a cream-faced boy! I am shocked, I am. Now I’ll take every penny you have, laddie, to pay my damages. Every coin, now, be prompt, don’t make me shake it out of you.’

‘I have none,’ Wintrow told him angrily. ‘Nor would I give you any I had!’

The man stood over him and poked him with his bat. ‘Who’s your father, then? Someone’s going to have to pay.’

‘I’m alone,’ Wintrow snapped. ‘No one’s going to pay you or your master anything for what I did. I did Sa’s work. I did what was right.’ He glanced past the man at the coffle of slaves. Those who could stand were getting to their feet. Lem had crawled over by Cala’s body. He stared intently into her upturned eyes, as if he could also see what she now beheld.

‘Well, well. Right for her may be wrong for you,’ the little man pointed out snidely. He spoke briskly, like rattling stones. ‘You see, in Jamaillia, slaves are not entitled to Sa’s comfort. So the Satrap has ruled. If a slave truly had the soul of a man, well, that man would never end up a slave. Sa, in his wisdom, would not allow it. At least, that’s how it was explained to me. So. Here I am with one dead slave and no day’s work. The Satrap isn’t going to like that. Not only are you a killer of his slaves, but a vagrant, too. If you looked like you could do a decent day’s work, I’d clap some chains and a tattoo on you right now. Save us all some time. But. A man must work within the law. Ho, guard!’ The little man lifted his bat and waved it cheerily at a passing city guard. ‘Here’s one for you. A boy, no family, no coin, and in debt to me for damage to the Satrap’s slaves. Take him in custody, would you? Here, now! Stop, come back!’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: