По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

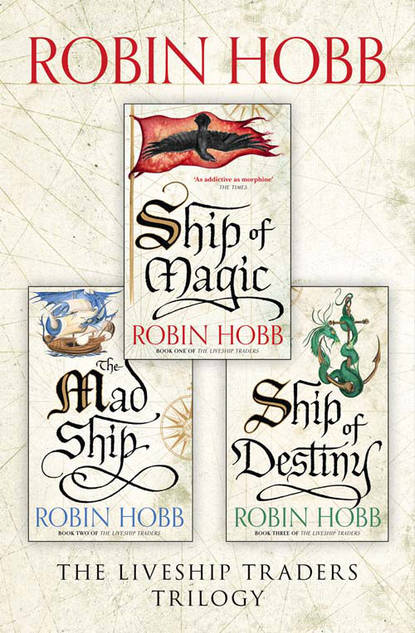

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A cry aft turned her head. She did not have a clear view, but the shouts from below told her that the serpent had been sighted again. ‘The bastard’s coming right after us!’ someone yelled, and the captain bellowed for the hunters to go aft, and be ready to drive it off with arrows and harpoons. Althea, clinging to her perch, caught one clear glimpse of the creature bearing down on them. Its mouth still gaped wide, the chain dangling from the corner. Somehow it had severed the heavy hemp line that had attached the barrels to it. The arrows and harpoons stood out from its throat. Its immense eyes caught a bit of the first feeble light of dawn and reflected it as red anger. Never before had Althea seen an emotion shine so fiercely in an animal’s countenance. Taller and taller it reared up from the water, impossibly tall, much too long to be something alive.

It struck the ship with every bit of force it could muster. The immense head landed on the afterdeck with a solid smack, like a giant hand upon a table. The bow of the ship leapt up in response and Althea was nearly thrown clear of the rigging. She clung there, voicing her terror in a yell that more than one echoed. She heard the frantic twanging of arrows loosed. Later, she would hear how the hunters sprung fearlessly forward, to thrust their spears into the creature over and over again. But their actions were unneeded. It had been dying even as it charged up on them. It lay lifeless on the deck, wide eyes staring, maw dribbling a milky fluid that smoked where it fell on the wooden deck. Gradually the weight of its immense body drew its head back and down, to vanish into the dark waters from whence it had sprung. Half the after-rail went with it. It left a trough of scarred wood smoking in its wake. Hoarsely the captain ordered the decks doused with seawater.

‘That wasn’t just an animal,’ a voice she recognized as Brashen’s said. There was both awe and fear in his voice. ‘It wanted revenge before it died. And it damned near got it.’

‘Let’s get ourselves out of here,’ the mate suggested.

All over the ship, men sprang to with a will as the grudging sun slowly reached toward them over the sea.

He came to the foredeck in the dead of night on the fourth day of their stay in Jamaillia. Vivacia was aware of him there, but then, she was aware of him anywhere on board her. ‘What is it?’ she whispered. The rest of the ship was still. The single sailor on anchor-watch was at the stern, humming an old love song as he gazed at the city’s scattered lights. A stone’s throw away, a slaver rocked at anchor. The peace of the scene was spoiled only by the stench of the slave-ship and the low mutter of misery from the chained cargo within it.

‘I’m going,’ he said quietly. ‘I wanted to say goodbye.’

She heard and felt his words, but they made no sense to her. He could not mean what the words seemed to say. Panicky, she reached for him, to grope inside him for understanding, but somehow he held that back from her. Separate.

‘You know I love you,’ he said. ‘More important, perhaps, you know I like you, too. I think we would have been friends even if we had not been who we are, even if you had been a real person, or I just another deckhand—’

‘You are wrong!’ she cried out in a low voice. Even now, when she sensed his decision to abandon her hovering in the air, she could not bring herself to betray him. It was not, could not be real. There was no sense in crying an alarm and involving Kyle in this. She would keep it private, between the two of them. She kept her words soft. ‘Wintrow. Yes, in any form we would be friends, though it cuts me to the quick when you seem to say I am not a real person. But what is between us, ship and man, oh, that could never be with any other! Do not deceive yourself that it could. Don’t salve your conscience that if you leave me I can simply start chatting with Mild or share my opinions with Gantry. They are good men, but they are not you. I need you, Wintrow. Wintrow? Wintrow?’

She had twisted about to watch him, but he stood just out of her eye-shot. When he stepped up to her, he was stripped to his underwear. He had a very small bundle, something wadded up inside an oilskin and tied tight. Probably his priest’s robe, she thought angrily to herself.

‘You’re right,’ he said quietly. ‘That’s what I’m taking, and nothing else. The only thing of mine I ever brought aboard with me. Vivacia. I don’t know what else I can say to you. I have to go, I must, before I cannot leave you. Before my father has changed me so greatly I won’t know myself at all.’

She struggled to be rational, to sway him with logic. ‘But where will you go? What will you do? Your monastery is far from here. You have no money, no friends. Wintrow, this is insanity. If you must do this, plan it. Wait until we are closer to Marrow, lull them into thinking you’ve given up and then…’

‘I think if I don’t do this now, I will never do it at all.’ His voice was quietly determined.

‘I can stop you right now,’ she warned him in a hoarse whisper. ‘All I have to do is sound the alarm. One shout from me and I can have every man aboard this vessel after you. Don’t you know that?’

‘I know that.’ He shut his eyes for a moment and then reached out to touch her. His fingertips brushed a lock of her hair. ‘But I don’t think you will. I don’t think you would do that to me.’

That brief touch and then he straightened up. He tied his bundle to his waist with a long string. Then he clambered awkwardly over the side and down the anchor chain.

‘Wintrow. You must not. There are serpents in the harbour, they may…’

‘You’ve never lied to me,’ he rebuked her quietly. ‘Don’t do it now to keep me by you.’

Shocked, she opened her mouth, but no words came. He reached the cold, cold water and plunged one bare foot and leg into it. ‘Sa preserve me,’ he gasped, and then resolutely lowered himself into the water. She heard him catch his breath hoarsely in its chill embrace. Then he let go of the chain and paddled awkwardly away. His tied bundle bobbed in his wake. He swam like a dog.

Wintrow, she screamed. Wintrow, Wintrow, Wintrow. Soundless screams, waterless tears. But she kept still, and not just because she feared her cries would rouse the serpents. A terrible loyalty to him and to herself silenced her. He could not mean it. He could not do it. He was a Vestrit, she was his family ship. He could not leave her, not for long. He’d get ashore and go up into the dark town. He’d stay there, an hour, a day, a week, men did such things, they went ashore, but they always came back. Of his own free will, he’d come back to her and acknowledge that she was his destiny. She hugged herself tightly and clenched her teeth shut. She would not cry out. She could wait, until he saw for himself and came back on his own. She’d trust that she truly knew his heart.

‘It’s nearly dawn.’

Kennit’s voice was so soft, Etta was scarcely sure she had heard it. ‘Yes,’ she confirmed very quietly. She lay alongside his back, her body not quite touching his. If he was talking in his sleep, she did not wish to wake him. It was seldom that he fell asleep while she was still in the bed, seldom that she was allowed to share his bedding and pillows and the warmth of his lean body for more than an hour or two.

He spoke again, less than a whisper. ‘Do you know this piece? “When I am parted from you, The dawn light touches my face with your hands.”’

‘I don’t know,’ Etta breathed hesitantly. ‘It sounds like a bit of a poem, perhaps… I never had much time for the learning of poetry.’

‘You have no need to learn what you already are,’ he said quietly. He did not try to disguise the fondness in his voice. Etta’s heart near stood still. She dared not breathe. ‘The poem is called, From Kytris To His Mistress. Older than Jamaillia, from the days of the Old Empire.’ Again there was a pause. ‘Ever since I met you, it has made me think of you. Especially the part that says, “Words are not cupped deeply enough to hold my fondness. I bite my tongue and scowl my love, lest passion make me slave.’” A pause. ‘Another man’s words, from another man’s lips. I wish they were my own.’

Etta let the silence follow his words, savoured them as she committed them to memory. In the absence of his breathless whisper, she heard the deep rhythm of his breathing in harmony with the splash and gurgle of the waves against the ship’s bow. It was a music that moved through her with the beating of her blood. She drew a breath and summoned all her courage.

‘Sweet as your words are, I do not need them. I have never needed them.’

‘Then in silence, let us bide. Lie still beside me, until morning turns us out.’

‘I shall,’ she breathed. As gentle as a drifting feather alighting, she laid her hand on his hip. He did not stir, nor turn to her. She did not mind. She did not need him to. Having lived for so long with so little, the words he had spoken to her now would be enough to last her a life. When she closed her eyes, a single tear slid forth from beneath her lashes.

In the dimness of the captain’s cabin, a tiny smile curved his wooden features.

23 JAMAILLIA SLAVERS (#ulink_dd19dee7-f19e-54c6-b164-476f91bd0503)

THERE WAS A SONG he had learned as a child, about the white streets of Jamaillia shining in the sun. Wintrow found himself humming it as he hurried down a debris-strewn alley. To either side of him, tall wooden buildings blocked the sun and channelled the sea wind. Despite his efforts, the saltwater had reached his priest’s robe. The damp bure slapped and chafed against him as he walked. The winter day was unusually mild, even for Jamaillia. He was not, he told himself, very cold at all. As soon as his skin and robe dried completely, he’d be fine. His feet had become so calloused from his days on shipboard that even the broken crockery and splintered bits of wood that littered the alley did not bother him much. These were things he should remember, he counselled himself. Forget the growling of his empty belly, and be grateful that he was not overly cold.

And that he was free.

He had not realized how his confinement on the ship had oppressed him until he waded ashore. Even before he had dashed the water from his skin and donned his robe, his heart had soared. Free. He was many days from his monastery, and he had no idea how he would make his way there, but he was determined he would. His life was his own again. To know he had accepted the challenge made his heart sing. He might fail, he might be recaptured or fall to some other evil along the way, but he had accepted Sa’s strength and acted. No matter what happened to him after this, he had that to hold to. He was not a coward.

He had finally proved that to himself.

Jamaillia was bigger by far than any city he had ever visited. The size of it daunted him. From the ship, he had focused on the gleaming white towers and domes and spires of the Satrap’s Court in the higher reaches of the city. The steaming of the Warm River was an eternal backdrop of billowing silk to these marvels. But he was in the lower part of the city now. The waterfront was as dingy and miserable as Cress had been, and more extensive. It was dirtier and more wretched than anything he had ever seen in Bingtown. Dockside were the warehouses and ship-outfitters, but above them was a section of town that seemed to consist exclusively of brothels, taverns, druggeries and run-down boarding houses. The only permanent residents were the curled beggars who slept on doorsteps and within scavenged hovels propped up between buildings. The streets were near as filthy as the alleys. Perhaps the gutters and drains had once channelled dirty water away; now they overflowed in stagnant pools, green and brown and treacherous underfoot. It was only too obvious that nightsoil from chamberpots was dumped there as well. A warmer day would probably have produced an even stronger smell and swarms of flies. So there, he reminded himself as he skirted a wider puddle, was yet another thing to be grateful for.

It was early dawn, and this part of the city slept on. Perhaps there was little that folk in this quarter of town deemed worth rising for. Wintrow supposed that night would tell a different story on these streets. But for now, they were deserted and dead, windows shuttered and doors barred. He glanced up at the lightening sky and hastened his steps. It would not be too much longer before his absence from the ship would be noticed. He wanted to be well away from the waterfront before then. He wondered how energetic his father would be in the search for him. Probably very little on his own account; he only valued Wintrow as a way to keep the ship content.

Vivacia.

Even to think the name was like a fist to his heart. How could he have left her? He’d had to, he couldn’t go on like that. But how could he have left her? He felt torn, divided against himself. Even as he savoured his liberty, he tasted loneliness, extreme loneliness. He could not say if it were his, or hers. If there had been some way for him to take the ship and run away, he would have. Foolish as that sounded, he would have. He had to be free. She knew that. She must understand that he had to go.

But he had left her in the trap.

He walked on, torn within. She was not his wife or his child or his beloved. She was not even human. The bond they shared had been imposed upon them both, by circumstance and his father’s will. No more than that. She would understand, and she would forgive him.

In the moment of that thought, he realized that he meant to go back to her. Not today, nor tomorrow, but some day. There would come a time, in some undecided future, perhaps when his father had given up and restored Althea to the ship, when it would be safe for him to return. He would be a priest and she would be content with another Vestrit, Althea or perhaps even Selden or Malta. They would each have a full and separate life, and when they came together of their own independent wills, how sweet their reunion would be. She would admit, then, that his choice had been wise. They would both be wiser by then.

His conscience suddenly niggled at him. Did he hold the intent to return as the only way to assuage his conscience? Did that mean, perhaps, that he suspected what he did today was wrong? How could it be? He was going back to his priesthood, to keep the promises made years ago. How could that be wrong? He shook his head, mystified at himself, and trudged on.

He decided he would not venture into the upper reaches of the city. His father would expect him to go there, to seek sanctuary and aid from Sa’s priests in the Satrap’s Temple. It would be the first place his father would look for him. He longed to go there, for he was certain the priests would not turn him away. They might even be able to aid him to return to his own monastery, though that was a great deal to ask. But he would not ask them, he would not bring his father banging on their doors demanding his return. At one time, the sanctuary of Sa’s temple would have protected even a murderer. But if the outer circles of Jamaillia had degraded to this degree, he somehow doubted that the sanctity of Sa’s temple would be respected as it once was. Better to avoid causing them trouble. There was really no sense to pausing in the city at all. He would begin his long trek across the satrapy of Jamaillia to reach his monastery and home.

He should have felt daunted at the thought of that long journey. Instead he felt elated that, at long last, it was finally begun.

He had never thought that Jamaillia City might have slums, let alone that they would comprise such a large part of the capital city. He passed through one area that a fire had devastated. He estimated that fifteen buildings had burned to the ground, and many others nearby showed scorching and smoke. None of the rubble had been cleared away; the damp ashes gave off a terrible smell. The street became a footpath beaten through debris and ash. It was disheartening, and he reluctantly gave more credence to all the stories he had heard about the current Satrap. If his idle luxury and sybaritic ways were as decadent as Wintrow had heard, that might explain the overflowing drains and rubbish-strewn streets. Money could only be spent once. Perhaps taxes that should have repaired the drains and hired street watchmen had been spent instead on the Satrap’s pleasures. That would account for the sprawling wasteland of tottering buildings, and the general neglect he had seen down in the harbour. The galleys and galleasses of Jamaillia’s patrol fleet were tied there. Seaweed and mussels clung to their hulls, and the bright white paint that had once proclaimed they protected the interests of the Satrap was flaking away from their planks. No wonder pirates now plied the inner waterways freely.

Jamaillia City, the greatest city in the world, the heart and light of all civilization, was rotting at the edges. All his life he had heard legends of this city, of its wondrous architecture and gardens, its grand promenades and temples and baths. Not just the Satrap’s palace, but many of the public buildings had been plumbed for water and drains. He shook his head as he reluctantly waded past yet another overflowing gutter. If the water was standing and clogged here below, how much better could things be in the upper parts of the city? Well, perhaps things were much better along the main thoroughfares, but he’d never know. Not if he wanted to elude his father and whatever searchers he sent after him.

Gradually the circumstances of the city improved. He began to see early vendors offering buns and smoked fish and cheese, the scents of which made his mouth water. Doors began to be opened, people came out to take the shutters down from the windows and once more display their wares. As carts and foot-traffic began to crowd the streets, Wintrow’s heart soared. Surely, in a city of this size, with all these people milling about, his father would never find him.

Vivacia stared across the bright water to the white walls and towers of Jamaillia. In hours, it had not been that long since Wintrow left. Yet it seemed lifetimes had passed since he had clambered down the anchor chain and swum away. The other ships had obscured her view of him. She could not even be absolutely certain he had reached the beach safely. A day ago, she would have insisted that if something had happened to him, she would have felt it. But a day ago, she would have sworn that she knew him better than he did himself, and that he could never simply leave her. What a fool she had been.